So Mayer on the Re-Release of Europa (1931)

On Stefan and Franciszka Themerson’s celebrated experimental anti-fascist film poem, Europa

On Stefan and Franciszka Themerson’s celebrated experimental anti-fascist film poem, Europa

In 1940, Stefan and Franciszka Themerson’s celebrated experimental anti-fascist film poem, Europa (1931), was looted by the Nazis from the Vitfer Film Laboratory in Paris and destroyed. Or so it was thought. Then, in 2019, a copy was discovered at the German Federal Archives in Berlin, with the recovered film finally screening again for the first time in more than 80 years at this year’s BFI London Film Festival.

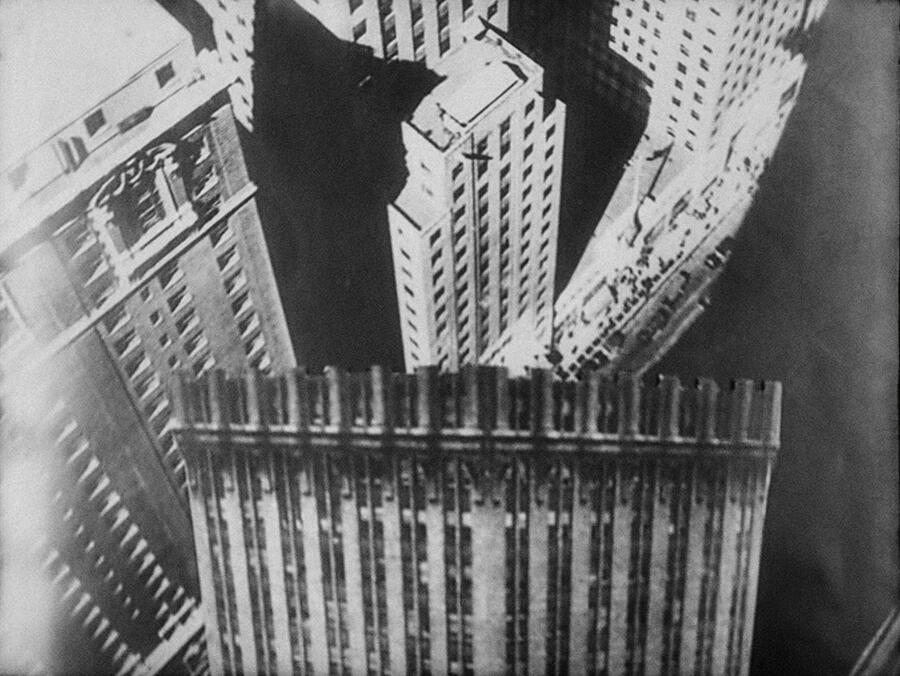

A vivid, twelve-minute, black and white compendium of experimental techniques, Europa blends cameraless photography – produced on a ‘trick table’ of glass covered with tracing paper – with graphic animation and filmed footage of actors. Watching it, I think of the Themersons’ contemporary, Sergei Eisenstein, who argued in ‘A Dialectic Approach to Film Form’ (1949) that film must adopt radical formal strategies, such as montage, to engage audiences in Marxist revolution. The actors’ stark gestures are reminiscent of their theatrical contemporaries in Germany, working on the plays of Bertolt Brecht. The cameraless animation recalls both Fernand Léger’s short film Ballet mécanique (Mechanical Ballet, 1924) and filmmaker Lotte Reiniger’s striking, cut-out animations of the 1920s. In other words, a transnational, interconnected, continent-wide conversation and exchange comes into view: not just the stylistic strategies implied by the term ‘modernism’, but the radical politics, too, including ideas around technology, language and artistic exchange.

Europa’s re-emergence also resonates with a question that runs through an essay I wrote last year on the long-lasting effects of the Nazi repression of emergent queer cultures: what happens to our understanding of both past and present when a ‘lost’ film is found? In A Nazi Word for a Nazi Thing (2020), I strove to think about the supercharged rush of Europa in its time, and how we reconnect to that now as artists, curators, critics and viewers. The temptation to regard the work piously as a museum piece, to mourn its energy as extinguished, goes against Europa’s own exuberant, angry presentness, its demand that we meet it in its moment and its making. There’s a complex story to tell about how the film came to be, and how it came to be found. (Pamela Hutchinson told it very well in an article for the Independent newspaper last year.) But there are other ways to encounter the film that do not ossify it as an archival object. As Lola Olufemi writes in Experiments in Imagining Otherwise (2021): ‘The archive, with its shadows and gaps, is a colonial invention in narrative consistency […] What if [it were] a continuous, fickle, evolving set of processes that eschews definition, or concreteness, or knowing.’

When ‘lost’ films are re-screened, it is within a ‘narrative consistency’ that details production, disappearance, rediscovery and restoration: an important narrative that nevertheless blunts the work’s intensity. In the case of Europa, that narrative also includes restitution, as it is the first film work to be restituted by the Commission for Looted Art in Europe (to the Themersons’ niece, Jasia Reichardt). It is thus part of a small and significant group of films lost specifically to Nazi expropriation and destruction. In A Nazi Word for a Nazi Thing, I ask how we can tell and hear that story without allowing it to over-determine our response when the film is screened today.

Nazi looting and restitution remain uniquely emotionally and culturally charged, but they were hardly unique acts. Fascists learned the effectiveness of cultural dispossession and erasure from centuries of European colonialism – and, like colonial powers, exercised it by hoarding looted materials. The rediscovery of Europa in Germany’s Federal Archives is a reminder that all such archives are full of loot taken forcibly from other cultures and communities. Whereas the conventional narrative is that archives rescue and preserve materials for posterity, the story of Europa underscores how ‘preservation’ can mean the removal of a work from a living culture.

MayDay Rooms, a radical leftist archive in London, uses the term ‘collective activation’ to describe hands-on community engagement with its archival holdings, recognising the importance of pushing back against the museal, taxonomical, butterfly-pinning tendencies of European collecting. British artist filmmakers such as John Akomfrah, Onyeka Igwe, Isaac Julien and Alberta Whittle have all been differently activating colonial visual archives to contest the ownership of those captured in colonial photographs and footage, and to devise new contexts that can at once hold memory and create living futures.

When I was writing A Nazi Word for a Nazi Thing in late 2019, there were plans to mark its launch by screening some of the films it discusses, including Julien’s Looking for Langston (1989), which reaches back to the interwar years in queer Harlem, and two films considered to mark the birth of European LGBTQ+ cinema: Different from the Others (Richard Oswald, 1919) and Girls in Uniform (Leontine Sagan, 1931). Although lockdown intervened, these screenings were intended as a reactivation of films that had been expropriated, and a celebration of their re-entry into cultural conversation not as museum objects but as still-charged, complex and living subjects in an ongoing practice of queer cinematic collective activation.

Europa likewise makes a strong case for its own nowness: it eschews narrative consistency or continuity, preferring repetition and patterning, and refuses to be contained by the state. Watching it in 2021 provides a similar feeling to seeing the gay dancehall in Different from the Others: here is a modernity at once recognisable and lost to us, interrupted and yet powerfully present. Europa’s density of images – edited with fast cuts and superimpositions, rhythmic repetitions and graphic matches – captures not only the words of Anatol Stern’s 1925 futurist poem on which it is based, but its explosive futurist formal strategies for making meaning.

Taking Olufemi’s suggestion for the archive as a ‘continuous, fickle, evolving set of processes’ that can induce our ethical imagination, I’m currently working on a non-linear narrative project about interwar cinema that looks at queer and experimental film histories as a form of speculative fiction. In a sense, Europa is a speculative fiction of its own: a dystopian warning about the repression and erasure of the very modernist ideas and strategies it is celebrating; a protest against populist strongmen manipulating working-class voters through a supine media.

Part of what feels visceral about Europa today is that the film’s adaptive, collaborative way of working allows us to retrospectively ask, ‘What if?’ about the past. I refer to this as a subjunctive that stands against the imperative: a way of freeing ourselves from the insistent grip of history. To watch Europa in all its vitality is a reminder that the narrative of lostness that surrounds such films is less about the status or story of any individual text or image (although that, too, is materially important) and more about how we can reflect on and work to mend the severed cultural genealogy it represents. What if Europa’s warning had been heeded? What if the film – which faced the circulation challenges that still confront artists’ film and video, even in the digital era – had been more widely screened before it was expropriated? What connections might have been made? What resistance might have been actualised? What might have been continuity rather than memory?

The Themersons themselves investigated this possibility: via their Gaberbocchus Press, they published an English facsimile edition of Europa in 1962, translated by Stefan with poet Michael Horovitz. The edition included surviving stills from the film, as well as reviews from its first screenings. In 1983, at the London Film-Makers’ Co-op – one of the capital’s key loci of experimental art-making during the 1970s and early ’80s – Stefan created a reconstruction using surviving stills from the film. Artist Piotr Zarębski also made an homage to the original, Europa II (1988), based on his correspondence with Stefan. These transgenerational and transnational collaborations maintained Europa as a living text, one that is polyvocal, collaborative, open to its moment – a vulnerable, courageous thing to be.

The most striking repeated motifs in the film are grasses growing and a beating heart, filmed on the trick table: symbols of movement, exchange and aliveness. Europa is named for the notion of shared histories and futures, a defiance of borders. Its creative practice and reconstruction highlight collaboration through mobility – of ideas, forms and even authorship. Writing a book about queer anti-fascism during the pandemic felt lonely, sometimes risky and sometimes pointless. But the works I was writing about all railed against the idea of ‘lostness’ and even of ‘foundness’: they were made, like Europa, to speak and keep speaking, even if listeners turned away. Writing for now, and writing for posterity, are, Europa reminds us, the same thing, because now and the future are co-constitutive. It’s challenging to remember this in the grip of crisis and emergency, in a moment when fascisms are once again severing us from possibilities. Europa, with its brilliant appetite for radical ways of sharing, speaks (as if) from the future it imagines, one where it was – as maybe now it will be – heard. And that gives me a reason to keep making, as well as to keep watch.

This article first appeared in frieze issue 224 with the headline ‘Keeping Watch’.

Main image: Stefan and Franciszka Themerson, Europa, 1931, film still