That’s Life!

A re-print of General Idea’s radical, now defunct FILE Magazine celebrates its idiosyncratic brilliance

A re-print of General Idea’s radical, now defunct FILE Magazine celebrates its idiosyncratic brilliance

Cranking Jean-Luc Godard’s sly oxymoron, ‘This is not just an image. This is just an image,’ to the sort of ultra-high frequency that usually only bats can hear, FILE Megazine ran for 26 issues until 1989, when the last one, barely legal at 17, declared that it had achieved its aim of becoming ‘an alternative to the Alternative press’.

Founded in 1972 by the Toronto-based artists’ group General Idea (A.A. Bronson, Felix Partz and Jorge Zontal), the magazine was a powerful organ for their collaborative, iconoclastic practice, enacting a typographic and linguistic putsch not only on its chosen subject matter but also on itself. For example, the cover for their ‘Mondo Cane Kama Sutra Issue’ (1983) depicts General Idea decked out, somewhat disturbingly, as satanic-lite poodles, while the ‘FILE Retrospective Issue’ (1984) portrays the trio as flushed-cheeked toddlers tucked up side by side in bed, their three pairs of hands almost certainly busy below the covers. This editorial identification is deliberately illusory (hence the alter egos), for FILE was really about ‘you’, not about ‘us’.

FILE’s incorporation of other magazines into its own publication strengthened this challenge to authorial supremacy by encouraging a polyphonic editorial. The ‘Art News Issue’ of Christmas 1986 is constructed of an appropriated ARTnews front cover, Sherrie Levine pensive in the foreground, FILE’s nameplate floating like a gaseous cloud above her head. More infamously, published in the same year was Malcolm McLaren’s insert/intervention ‘Chicken’ in the bumper ‘Sex, Drugs, Rock ’n’ Roll and Art & Text Issue’, itself guest-edited by the critic Paul Taylor, founder of Art & Text. ‘Chicken’ was a pretend proposal (or was it?) for a new sex magazine specially for children and teenagers, constructed from old publicity material from the McLaren-managed band Bow Wow Wow: a typically carnivalesque project by all three sets of editors – General Idea, then Taylor, then McLaren – its disruptive construction demonstrates something of the complexity of print production.

FILE’s extreme graphic competency, especially for a self-published venture, combined with General Idea’s interest in conventional distribution, Postmodernism and Pop, portends, as Rick Poynor might call it, ‘Surface Wreckage’; the type of wreckage here is that which has been filtered through the strata of the magazine’s radical content and reconfigured into a seductive ‘brand’. Bronson said recently, ‘FILE was, in many ways, an exercise in distribution. It has been written that we pioneered viral techniques in advertising and distribution, and I think that is true. The first issues of FILE were sent out primarily free to artists and key media people in Europe, North America and Japan (Andy Warhol and Joseph Beuys were among our first subscribers). We considered ourselves a kind of parasite within the magazine distribution system, piggy-backing on the visibility of larger publications.’ This shrewd yet seemingly instinctive strategy on General Idea’s part defies conventional monadic reading: it looks like a magazine, it smells like a magazine, it’s not a magazine.

Forget what you think you know about writing, publishing or art - FILE tested just about every possibility that such interstices can generate.

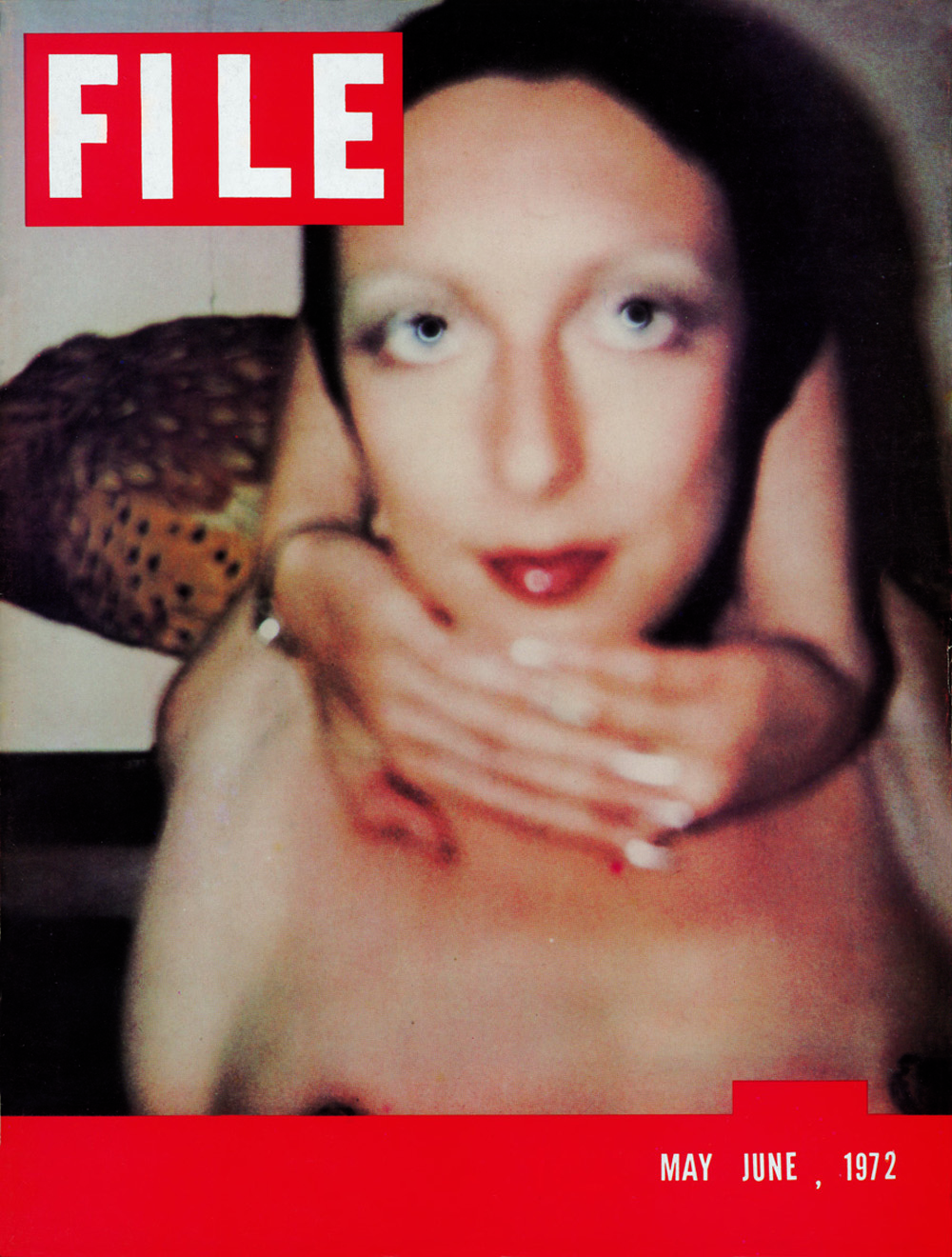

Based on the iconic red and white masthead of LIFE, North America’s favourite human interest magazine (which ran regular features such as ‘LIFE goes to a party’, documenting the soirées of selected suburbanites), FILE’s diagrammatic familiarity had a saponaceous quality to it, signalling to its readers that they were already part of its club because they recognized it, and further encouraging participation by directly promoting artists’ networks and actions. Unsurprisingly, Time-Life sued General Idea’s ‘interpretation’ of their logo, with the result that in 1976 FILE’s cheeky red and white masthead began a formalistic series of changes, first to silver studs on black leather, then to neon upper-case and on and on. FILE had grown up into a new creature of its own making – a ‘megazine’. The content, however, remained as (un)familiar as ever.

Forget what you think you know about writing, publishing or art, FILE’s impressively comprehensive approach, within and without its pages, has tested just about every form of practice that such interstices can generate. For in a time when most other art magazines were merely writing about art, FILE actually was art. Working from a basic premise of inclusive radicalism, the publication spliced surrounding art forms such as architecture, design, film, music and photography into a sharply prescient network of associations; this, suffused with the unremitting intelligent wit of General Idea, was unusual in that it was non-polemic and in that sense non-judgemental: everything has the potential to be of the same value, the reader’s investment is key.

The totalizing influence of JRP|Ringier’s reprint of all issues of FILE appears at first to be somewhat at odds with the bitty experimentation of General Idea’s practice. By drawing together simply all the parts of a magazine’s life, might its weaker spots be exposed to critique? How would one read such a behemoth? What would be its ‘purpose’?

In Jules Verne’s 20,000 Leagues under the Sea (1869) Captain Nemo has 12,000 volumes of reading material uniformly bound: ‘The world ended for me the day the Nautilus dived for the first time beneath the waves. On that day I bought […] my last pamphlets, my last newspapers, and since that time I would like to believe that mankind has neither thought nor written.’ The FILE reprint lobs just such a time-stopping punch, not in a reductive sense but in a productive one, in that it endures as the exemplar of its type: an artists’ magazine.

Such a ‘source book’ today is an invaluable tool against the tyranny of standardization and, by implication, repetitious description. The infinite strength of the serial publication is essentially temporal in nature; its ability to develop a constituency of readers over time is carefully balanced against the assumption that those very readers will forget much of what they have seen even six months ago. In a time when the time is always now, occlusion can play an important role in critical interaction, in that we must make our own minds up about what to discard and what to retain. And what better way to lose something you don’t need than by placing it in a complex heap of similar things?