Threads Across the Black Atlantic: Grace Wales Bonner

The menswear designer discusses the writers, artists and spiritual traditions that have influenced her

The menswear designer discusses the writers, artists and spiritual traditions that have influenced her

Sacred Threads

An instinctive pull towards my ancestors is something I feel deeply, both on a physical and a spiritual level. ‘A Time for New Dreams’, my recent exhibition at Serpentine Galleries in London, explored lineage, ancestry and brotherhood, positioning writers as oracles that connect generations to a rich and magical history. Thinkers such as Dawoud Bey, Robert Farris Thompson, Ben Okri, Ishmael Reed and Malidoma Patrice Somé have been key in shaping my understanding of the aesthetic threads of mysticism, spirituality and ritual that traverse time and place across the Black Atlantic. Their writing is my sacred scripture. Through it, I feel the multiplicity and simultaneity of everything, the polyrhythmicality of blended tradition. I have come to understand, too, how magic, suffering and history are stored in (and on) the body and passed through generations.

Reed, who wrote a text for my Serpentine show, told me: ‘Our collaboration was inevitable because we are synching across a common aesthetic.’ He explained that, in our culture, clothes talk, and that dressing is as fundamental to black cultural tradition as drumming. He shared another sacred text:

'Because it was illegal in slave-holding states to teach slaves to read, slaves could not communicate with each other in writing. But, because slaves of all backgrounds shared an oral history of storytelling coupled with a knowledge of textile production and African art – an art form which embodies African symbolic systems and designs – they discovered they were able to communicate complex messages in the stitches, patterns, designs, colours and fabrics of the American quilt […] The patterns told slaves how to get ready to escape, what to do on the trip, and where to go.’

Revelations. A Babaaláwo priest told me during an Ifá ceremony in Los Angeles that, in West African cultures, identity is traditionally expressed from a distance through cloth: patterns reveal who you are before anything else. It was an important insight for me to realize, as a designer, that working in cloth connects to Henry Louis Gates’s notion of ‘signifiyin(g)’: a black vernacular that includes ‘“marking”, “loud-talking”, “specifying”, “testifying”, “calling out” (of one’s name), “sounding”, “rapping”, and “playing the dozens”’.1

Rhythmized Textiles

‘A particular style of Mande and Mande-influenced narrow-strip textile, enlivened by rich and vivid suspensions of the expected placement of the weft-block – thus characterized by the famed off-beat phrasing of melodic accents in African and Afro-American music – introduces to the history of art an extraordinary idiom, unique to the black world.’ (Robert Farris Thompson, Flash of the Spirit: African and Afro-American Art and Philosophy, 1983)

Farris Thompson’s presentation of Mandean strip textiles, woven with off-beat phrasing, is an idea I always return to. Clothes communicate with a unique vibration. I often romanticize the idea of soulful dressing. The connections Farris Thompson presents between aesthetics and rhythmic composition are extensive: in another essay, he describes Jean-Michel Basquiat working across canvases, layering a complex universe of signs and symbols in syncopation with hard bop and Afro-Cuban jazz. The image of that collaged, improvised way of creating universes stuck with me.

A Time for New Dreams

It has been a true privilege to have worked closely with Okri on the Serpentine show. ‘A Time for New Dreams’ takes its name from the author’s 2011 collection of poetic essays, which proposes new ways of being in all aspects of life: from childhood, to knowledge, beauty and education. ‘Dramatic Moments in the Encounter between Picasso and African Art’ is one essay I found particularly transformative. It offers a radical and enchanting retelling of the history of Western art. Okri recounts the moment the African spirits took possession of the young Pablo Picasso’s soul. The spirits had been waiting for a moment to share their mystery and wisdom with the world, and used the artist as a vessel to channel their true nature into collective consciousness. In the words of Okri: ‘Kind of true.’

In my work, I often play with the flexibility of time. Through an Afro-futurist prism, I feel the freedom to be able to interpret different temporalities unshackled by history. Time can stretch out ... The ancestral realm feels prehistoric and eternal.

I believe the thinking, conjuring and creation that has come before shapes the future possibilities for my generation. These are the threads we weave with. My exploration of mysticism originates in African and Caribbean traditions (from animism to masquerade via Reed’s neo-hoodooism); the prophetic creations of Terry Adkins, Rotimi Fani-Kayode, David Hammons, James Hampton, Okri, Reed and Betye Saar, amongst others, are also in dialogue with this history.

In Face of the Gods (1993), Farris Thompson writes about the form and function of shrines in Afro-Atlantic spirituality: as portals into other realms, places, times, worlds and histories. Okri pushed me to look beyond aesthetic form and to think about the connections between rhythms, assemblage and the repurposing of objects, and the transformative nature of shrines. Beyond this, he offered that the shrine is manifested through the activity and invocation around it. He contributed several new works to ‘A Time for New Dreams’ (Invocations for the Shrine I–IV, 2019) responding to my hopes and intentions for what the space could provide on a physical and emotional level.

The Throne of the Third Heaven of the Nations’ Millennium General Assembly

Hampton’s Throne continues to be a sustaining source of fascination. Guided by religious visions, Hampton spent more than a decade secretly assembling a complex shrine in a rented garage in Washington, D.C., between 1950 and his death in 1964. By day, he lived as a janitor, but he spent his evenings fashioning elaborate offertories from discarded foil, light bulbs, furniture and cardboard he had collected in his neighbourhood. Hampton is important to me as he connects to the idea of art having the capacity to be a direct and intimate expression of spirituality. His story links to Reed’s ‘Neo-HooDoo Manifesto’ (1970), which states: ‘Neo-hoodoo believes that every man is an artist and every artist a priest.’

The Mind as an Orisha

‘The Mind as an Orisha’ is a new text by Reed that I commissioned for the Serpentine exhibition catalogue. It frames black intellectualism as a form of spiritual practice: for Reed, acquiring knowledge becomes a religious act.

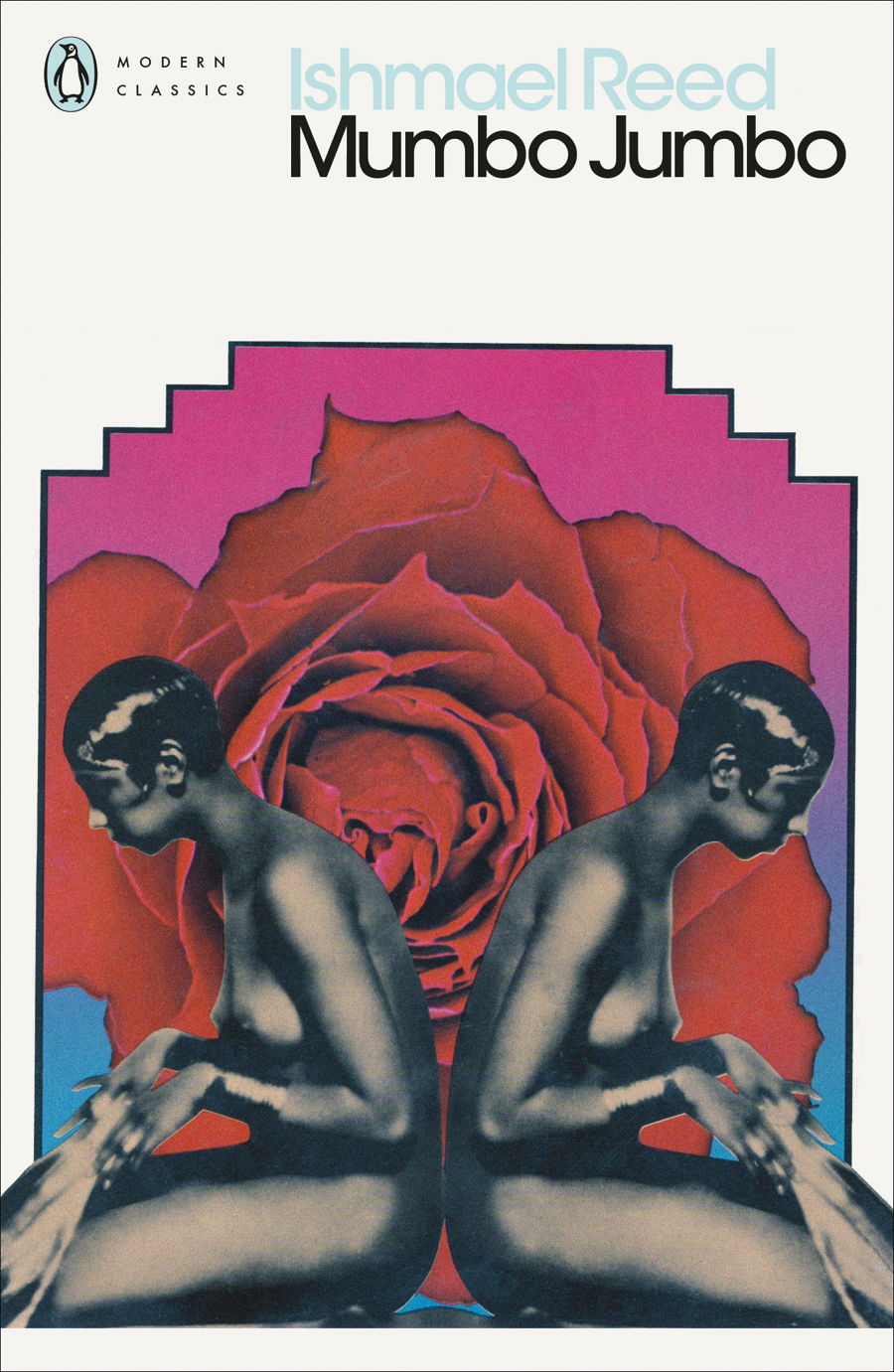

The worlds I imagine and explore are woven through fragments of texts, sounds, images, memories of characters and encounters I have read about; they are often manifestations of romanticized moods. My recent collection, titled after Reed’s novel Mumbo Jumbo (1972), was inspired by the world of a black university: black intellectuals gathering like a congregation, where discussion, practice and being together was its own kind of ritual and offered its own kind of salvation and transcendence. When I think about that world, I realize it is sketched partly through recollections of Ta-Nehisi Coates’s description of his peers at Howard University in Between the World and Me (2015), partly through recorded interviews and partly from a collection of Howard yearbooks from the 1980s I have been amassing. When I spoke to Rashid Johnson, whose work was also included in ‘A Time for New Dreams’, he told me about his research into W.E.B. Du Bois and historically black fraternities in the US. It is magical when everything starts to link up in the research process. Interwoven histories facilitate the present moment.

1 Henry Louis Gates, Jr., ‘The “Blackness of Blackness”: A Critique of the Sign and the Signifying Monkey’, 1983, Critical Inquiry 9:4, p. 687

Main image: James Hampton, The Throne of the Third Heaven of the Nations' Millennium General Assembly, c.1950-64. Courtesy: Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, D.C.

This article first appeared in frieze issue 204 with the title ‘Influences: Grace Wales Bonner’