Toppling Statues Is Not About History, It’s About the Present

The world demanded by Black Lives Matter is not the world in which Edward Colston belongs

The world demanded by Black Lives Matter is not the world in which Edward Colston belongs

Since 1895, a statue of the English merchant and slave-owner Edward Colston sat serenely on a pedestal looking over Bristol’s city centre. The bronze which depicts the wanton slaver in all gentility was, according to its plaque, ‘erected by citizens of Bristol as a memorial of one of the most virtuous and wise sons of their city’. Over a hundred years later, on 7 June 2020, it was also citizens of Bristol who, after a multi-racial, ten-thousand strong Black Lives Matter protest, decided that Colston was no longer the pride of their city. It was Bristol who tore Colston from his plinth and dropped him into the same harbour where he would have docked his slave ships in a spectacularly beautiful poetic turn.

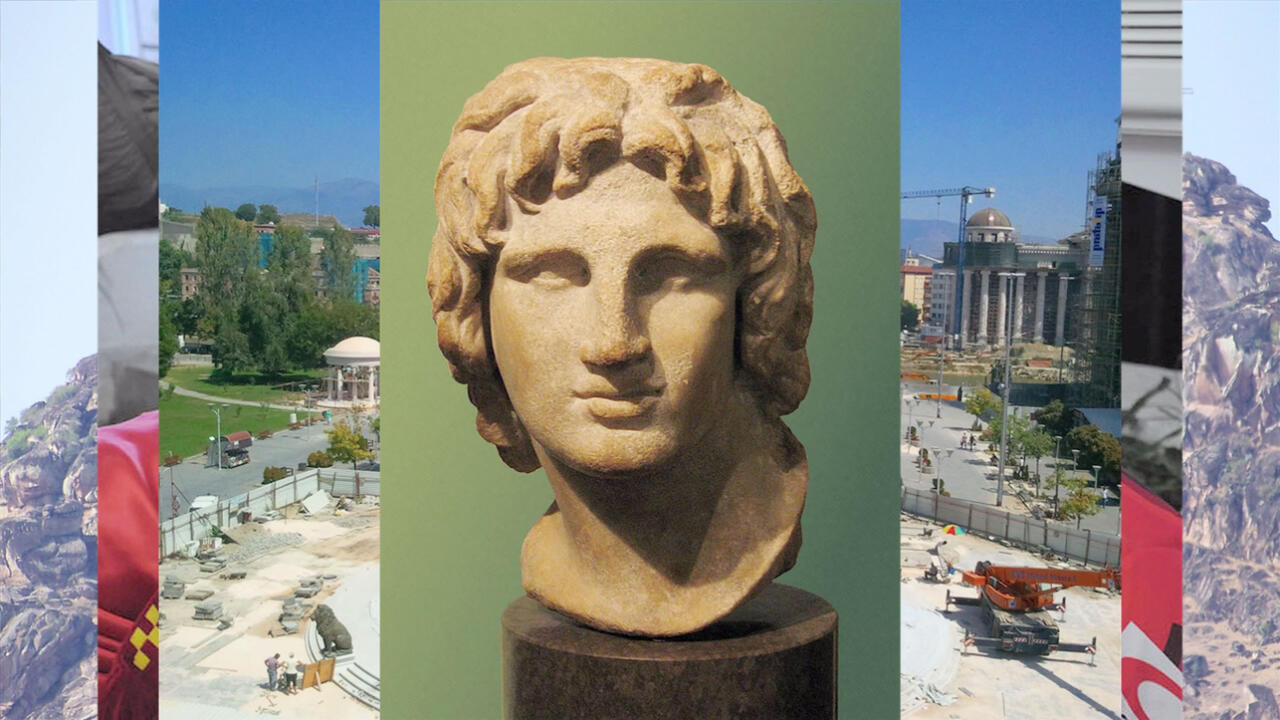

In the days since, the spectres of those who profited off the horrors of the slave trade and empire have been toppled across the UK. Labour councils have launched reviews into statues of slave traders with a view to removing them from public space and universities are scrambling to rename halls of residence. In the US, at least three statues of Christopher Columbus have been dismounted, including one in Boston, which woke up without a head. Belgium is taking down statues of King Leopold II – the cruel colonist whose fortune was built on millions of deaths and countless more severed hands in the Congo River basin. It seems that the familiar bronze and stonework across the West, which recasts the men who created the unjust global order as pensive white men, is facing a reckoning.

Colston’s toppling – filmed on shaky phones – has reignited a debate about which (or whose) histories public art should commemorate. This debate, however, is a red herring. At stake is the notion that art in the public realm is collectively owned. If that is the case, why then (like always) have a few monied individuals and fringe groups been able to thwart ordinary people in remaking the iconography of public space? I remember the first iteration of this debate – the near universal condemnation targeted by the press at students who sought to remove the fawning, colonial shrines to figures such as Cecil Rhodes from their campuses as part of a broader challenge to decolonise the British university, curriculum and all. Oriel College, Oxford, whose statue of Cecil Rhodes stands proudly over the city’s High Street, announced a consultation but quickly u-turned when donors threatened to withdraw millions.

The real debate is about where power lies. It is one about who gets to decide what we are confronted with in public space and, more importantly, what kind of society we are. The ‘pros and cons’ approach, balancing the wicked greed of these men against their ‘philanthropy’ and ‘benevolence’, is the same reason why establishment figures today continue to use charity to launder their reputations. Inheriting the wealth of these figures comes with the burden of doing PR work for them. In the refusal of protestors to accept this complicity in action, they have recognized and reckoned with a fundamental truth – one which many black and brown people had already known – that what happens here is causally related to what once happened over there, and continues to happen over there, and happens right here in Britain.

If the broader context has shown anything, it’s that it was never about statues, or plaques. It is not about history, it is about the present. The world remains a deeply unjust place, one in which vicious greed allows a few to amass obscene wealth through ruthless exploitation. This exploitation is embedded in our cultures, and made invisible by symbolism. Indeed, the same corporations who declare their shallow commitments to racial justice rely on the labour of black and brown people in the Global South under the most horrifying conditions. Here in the West, it is their property that police brutality protects. To that end, demonstrators were modelling the kind of world that is at stake, acting collectively to upend not simply the iconography but the material structures which protect it and profit from exploitation and brutality. The project is not simply a moment, but a process to rid the world of such injustice.

The past few weeks have been replete with episodes and actions that were previously unthinkable. Against the backdrop of existential pandemic crisis, the Black Lives Matter re-emerged – stronger and more radical. We saw as the streets of cities and towns across the world filled with huge multi-racial crowds carrying homemade signs and chanting ‘Abolish the Police!’ and ‘Whose Streets, Our Streets!’. We’re seeing the collective action in service of rebuilding the Commons, in which power is held by the people and not by the monied. The world being demanded is not the world in which Colston belongs. If we get our way, everything he represents will be dead in the water, shrines and all.