Ulla Wiggen’s Discomforting Gaze

In her comprehensive retrospective at EMMA in Espoo, Finland, the artist questions the limits of human understanding in the age of technology

In her comprehensive retrospective at EMMA in Espoo, Finland, the artist questions the limits of human understanding in the age of technology

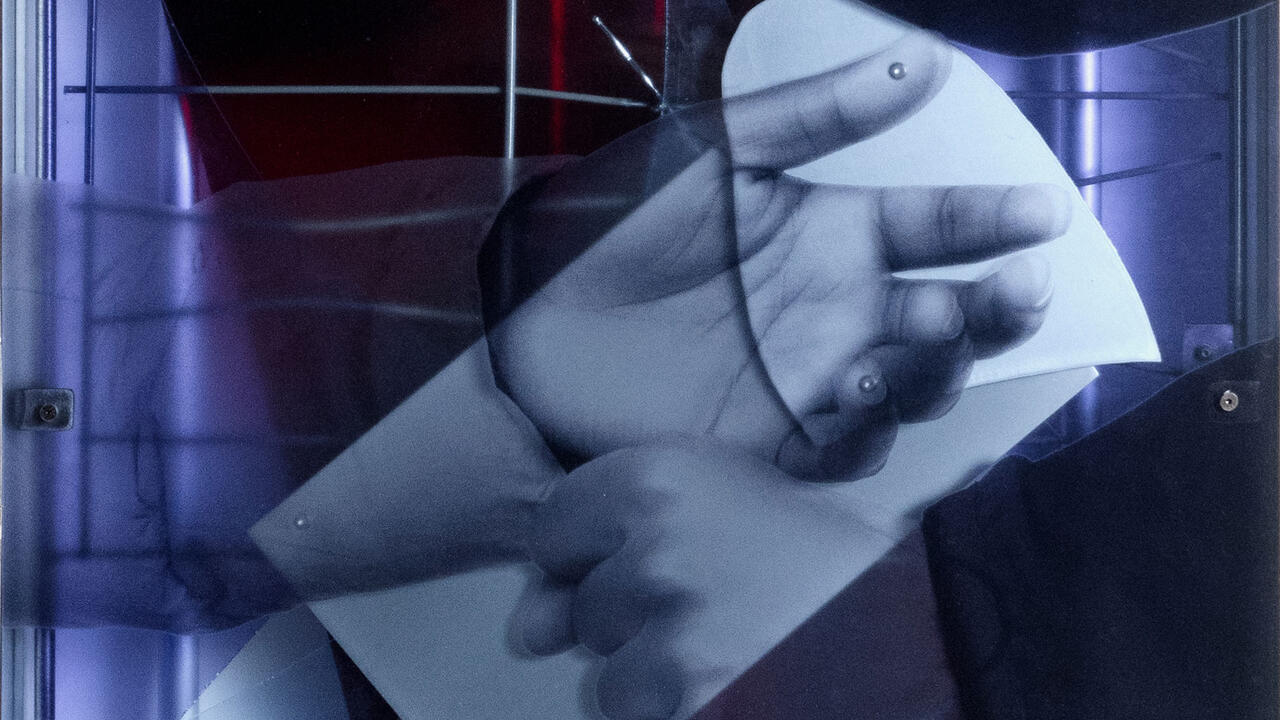

Swedish artist Ulla Wiggen is best known for her mid-1960s paintings of electronics and computers. These flat yet intricate works resemble blueprints, often depicting circuit boards dotted with transistors, capacitors and electrical pathways. The recent surge of interest in Wiggen’s early work is due to its foresight as much as its visual appeal. Her paintings prefigure today’s digital world and highlight how we interact with our devices only at an interface level. The exact function of each piece of hardware is even more opaque today, decipherable only to the most technically proficient.

‘Passage’, Wiggen’s extensive retrospective at the Espoo Museum of Modern Art (EMMA), features 45 works from the past 60 years. After a long hiatus from art, during which she worked as a psychotherapist, Wiggen recently resumed her practice, making paintings which reflect on how advances in science and technology have shaped our understanding of the world. Curated by Pernilla Wiik, the exhibition was previously presented at Fridericianum in Kassel, and will travel to Västerås Art Museum in Sweden next spring.

Among the recent works presented at EMMA is a series of iris paintings that Wiggen began toward the end of the last decade. These acrylic compositions on elliptical wooden panels range in diameter from approximately 50 centimetres to just over one metre. Iris XXIX Christopher (2023) features a green eye rendered with tightly packed, elongated brushstrokes in various tints. The outer rim is a deep moss green, while the pitch-black pupil is surrounded by a yellow-hued area – known as the collarette – with a craggy border that occasionally flares outward. In Iris IX (2018), the collarette is more uniformly green, while the outer rim is markedly more yellow.

Each iris painting is imbued with traces of individuality, reminding us that human bodies, unlike those of machines, are not standardized. Staring into these jet-black, oversized pupils can be unnerving. They reveal little in the way of personality or disposition, evoking the Cartesian notion that, while we are certain of our own thoughts, we can only infer those of others. Imagining them staring unblinkingly at screens suggests that, in our hypermediated culture, painting is a slow, even anachronistic, form of image-making.

Wiggen is at her most expressive – bordering on the surreal – in a series of paintings from the early 2010s that depict inner organs in medical textbook-like detail. In Passim (2014), a fleshy intestine stretches into a crisscrossing pattern, as if excised from the body and arranged for close examination. Mirroring the organ, the backdrop is a fleshy pink, with another intestine running along the image’s border. Similarly, Gyrus (2014) features four cross-sections of a pelvis and inner organs from above, resembling images produced by CT scanners.

The contrast to Wiggen’s early depictions of electronics is striking. Organs, unlike circuit boards, are lumpy, squishy and packed together in formations that are evolved rather than designed. Innards, like hardware components, usually remain hidden and are the domain of specialists. We know that genes, epigenetics and the health of our organs affect our emotions and thoughts. Yet, the precise impact they have on an individual level remains unknowable, giving these works an unsettling edge.

Throughout her career, Wiggen has traced what we cannot easily see: the microscopic details of circuit boards; fibrous bands on the iris; the topology of our inner organs. In doing so, she invokes Marshall McLuhan’s famous assertion that media extend our senses (Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man, 1964). Walking through Wiggen’s show at EMMA leaves one contemplating the limits of perception and whether our obsession with detail truly leads to a better understanding of ourselves and our place in the world.

Ulla Wiggen’s ‘Passage’ is on view at EMMA, Espoo, until 26 January 2025

Main image: Ulla Wiggen, Circuit Family, 1964, gouache on panel and gauze. Courtesy: © Ari Karttunen / EMMA – Espoo Museum of Modern Art