Weaving Histories

The impact of pre-Columbian techniques and designs on 20th-century artists

The impact of pre-Columbian techniques and designs on 20th-century artists

Sheila Hicks was a student at Yale when she took a class on pre-Columbian art in the mid-1950s. At the time, there was only one book in the library on Andean textiles, Raoul d’Harcourt’s Textiles of Ancient Peru and their Techniques (1934) — still essential reading on the subject — and she saw that Anni Albers had checked it out. Hicks was captivated by the textiles produced by Andean tribes in the centuries before the Spanish Conquest of 1532, as well as those predating the Incas who ruled for the preceding 100 years. ‘The richness of the pre-Incaic textile language is the most complex of any textile culture in history,’ she has said.1 The study of Andean textiles is virtually mandatory for anyone serious about weaving. Even before the Early Nazca period (approximately 1‒450), almost all weaving techniques — such as kelim, interlocking and eccentric tapestry; pattern weaves, weft scaffolding, twining and plaiting; lace, brocade, wrapped weaving and double cloth — were already known. Hicks was impressed by how, before written language, these ancient peoples organized ideas through thread. Her own earliest weavings — such as Muñeca (1957), which is titled after the woven dolls found in Andean tombs — were simply ‘attempts to understand material structures’.2

Hicks’s art tutor, the former Bauhaus professor Josef Albers, saw her experimenting with weaving techniques and introduced her to his wife, Anni. Hicks had been teaching herself to weave on a portable backstrap loom, as described in D’Harcourt’s book, requiring weavers to tension the warp threads with their own bodyweight by fastening them to a tree or post. It is a traditional Andean technique, which Anni introduced to her own students when she was teaching at Black Mountain College in the 1930s, after she and Josef first travelled to Mexico and saw it still in general use.

Today, Anni is widely acknowledged as a pioneer of Modernist textiles and is venerated as a grand matriarch of contemporary Fibre Art. Her study of the art and textiles of pre-Columbian America, which informed her view of textiles as a legitimate and progressive art form, is well known. The story of how Mesoamerican and Andean art came to shape Western Modernism is one that takes us back and forth across the Atlantic and the Equator, and which begins decades before Josef and Anni first scrambled up the high stone steps of Monte Albán in 1935.

While the term pre-Columbian is applicable to the entire American landmass before the arrival of Christopher Columbus in 1492, the most extensive civilizations emerged from two regions: what is now southern Mexico and Guatemala; and the Andes, from Columbia down through Ecuador and Peru to Chile. In the late-19th century, the largest collection of Andean textiles outside of Peru was in Berlin. In 1875, German archaeologists Wilhelm Reiss and Alphons Stübel excavated the Peruvian coastal necropolis of Ancón and discovered vast quantities of artefacts perfectly preserved by the arid desert conditions. Chief among these were the fine textiles used to wrap mummies, dating from the 6th to the 16th centuries, which Reiss and Stübel sent back to Germany, in particular to Berlin’s Museum für Völkerkunde (Ethnological Museum). Stübel later collaborated with Max Uhle, a young archaeologist from Dresden, who was sponsored by the museum to stage expeditions to Argentina and Bolivia in 1892.

Anni, who was born in 1899, grew up in the Berlin suburb of Charlottenberg and would have almost certainly visited the Museum für Völkerkunde as a child. Paul Klee and Franz Marc are also known to have visited it, along with fellow members of Der Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider) including Lyonel Feininger, Wassily Kandinsky and August Macke. The art of pre-industrial tribal cultures — then known as ‘primitive’ — was held in high esteem by Der Blaue Reiter, as it was by the German Expressionist group Die Brücke (The Bridge), which included Ernst Ludwig Kirchner and Emil Nolde. After World War I, Primivitism thrived in Modernist circles; industrialism was viewed with ambivalence, even abhorrence, and the handcrafted products of supposedly prelapsarian, pre-rational societies became models for the ideal integration of art and life, spirituality and daily use.

‘The richness of the pre-Incaic textile language is the most complex of any textile culture in history.’ Shelia Hicks

The theorization of Primitivism was influenced by Wilhelm Worringer’s book Abstraktion und Einfühlung (Abstraction and Empathy, 1908), which proposed that abstraction in tribal art was a response of its naïve, uncomprehending makers to the chaos of the world. Since postwar Europe had once again become chaotic, artists such as Klee concluded that the only appropriate artistic response was through the rationalizing structures of abstraction.

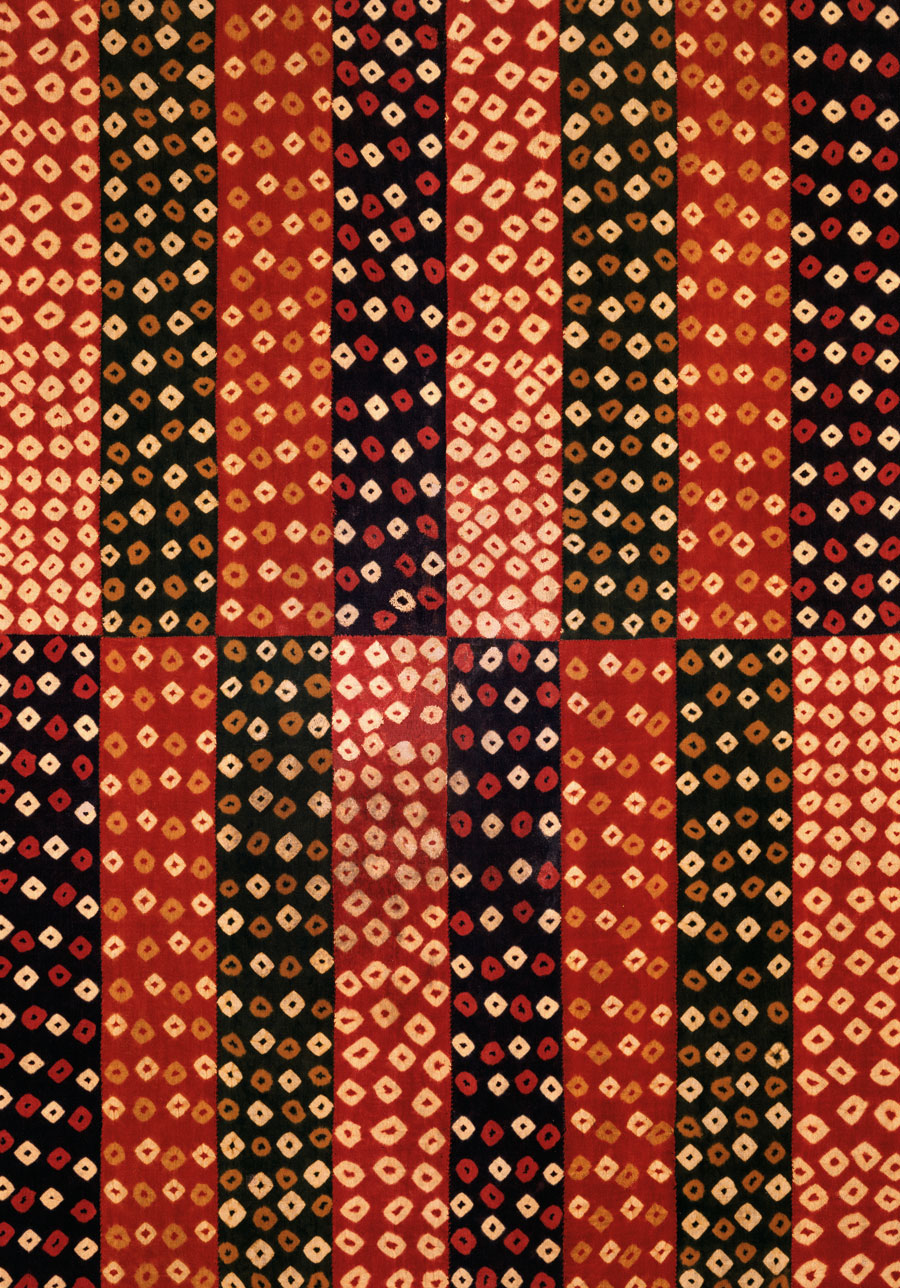

When Anni enrolled as a student at the Weimar Bauhaus in 1922, several Blaue Reiter artists — including Feininger, Kandinsky and Klee — were teaching there. The master of the ‘Preliminary Course’, Johannes Itten, also happened to be a weaver and a scholar of historic Andean textiles. The weaving workshop boasted more students than any other and was led (unofficially, at first) by the gifted student Gunta Stölzl, who remained at the school from 1919 until 1931, and departed as the only female Bauhaus master. Most of the students at the workshop were women. During the early years, they copied geometric Andean motifs, such as leaves or birds, from books by Reiss, Stübel and others. By 1923, however, the Bauhaus rejected such pictorial ornamentation in favour of abstraction, and the checkerboard and zigzag patterns common to Inca designs found their way into both weavings and paintings. The notion of the Gestamtkunstwerk — the total work of art, the synthesis of all art forms — is exemplified by the furniture that Stölzl began to produce, such as the colourful Afrikanischer Stuhl (African Chair, 1921) that she made with Marcel Breuer, in which she used the chair’s wooden armature as a tensioning loom.

One of the revolutionary ideas that emerged from the Bauhaus weaving workshop was the view that the warp — the vertical, structuring threads — is just as important as the weft — the thread woven through, usually the carrier of colour and pattern. At the Bauhaus, Anni learnt to twist warp threads in order to create open leno weaves, where the fabric separates to expose its underlying structure. From her studies of Peruvian textiles, she also developed double- and multi-ply weaves, in which she could create areas of solid colour, rather than having to hide the fixed warp with coloured weft.

In 1933, the Bauhaus, then located in Berlin, was closed by the Nazis and both Josef and Anni — by then salaried teachers — found themselves unemployed. The same year, John Rice, a classics professor with radical ideas about education, was setting up an alternative liberal arts college in North Carolina and was in need of a director. The young architect Philip Johnson recommended Josef and, since Anni was partly Jewish, the couple took their chance to leave Germany. Black Mountain College, which has assumed mythical status in the annals of art pedagogy, continued many of the principles first developed in the Bauhaus, with some of the same teachers. Anni once again taught weaving, while Bauhaus theatre teacher Xanti Schawinsky developed a ‘Stage Studies’ course.

Soon after arriving at Black Mountain College, Josef and Anni made their first trip to Mexico where, in 1935, they visited the ruins of Monte Albán, a magnificent Zapotec settlement on a hill near the city of Oaxaca. Over the following decades, they made a total of 14 trips to Mexico and South America, including Peru and Chile in the 1950s. Aside from the ancient art they saw, they also observed contemporary folk art techniques being practised, some of which were as influential on Anni as the artefacts she had seen in Berlin. In the mid-1930s, Anni broke with Bauhaus principles when she began using the term ‘pictorial weaving’ to refer to certain of her textiles, which she saw as abstract pictures — not meant to be used, only looked at. In a pivotal work titled Monte Albán (1936), she adopted the Mesoamerican ‘floating weft’ technique, in which an extra, non-structural weft thread is used to draw lines on the surface of the weave.

Beyond Black Mountain College, the Bauhaus was infiltrating America through other channels, too. In Chicago, in 1937, former Bauhaus teacher László Moholy-Nagy set up the New Bauhaus, with Walter Gropius as a consultant. Marli Ehrman, who had studied at the Weimar Bauhaus, was enlisted to head the weaving workshop. Moholy-Nagy and Ehrman were influential on a younger generation of American weavers, in particular Lenore Tawney who studied at the Chicago Institute of Design (as the New Bauhaus came to be called) between 1946 and 1947. Tawney was amongst the first wave of fibre artists recognized not as weavers or designers but as artists in their own right. In 1957, she moved to New York where she became close friends with Robert Indiana, Ellsworth Kelly and Agnes Martin. Her 1961 exhibition of loose, open-warp weavings at the Museum of Staten Island is considered a watershed moment in the legitimization of Fibre Art. In a statement for the exhibition, Martin wrote of the work’s ‘complete certainty of image, beyond primitive determination or any other aggressiveness, sensitive and accurate down to the last twist of the smallest thread’.3 Like Anni and Stölzl, Tawney acquired much of her technique by studying Peruvian textiles, although she was equally fascinated by the mechanics of the modern Jacquard loom.

Lenore Tawney was amongst the first wave of Fibre Artists recognized not as weavers or designers but as artists in their own right.

Also at the Chicago Institute of Design was Claire Zeisler, who studied alongside Tawney in the 1940s. Both were independently wealthy and middle-aged by the time they enrolled at art school: Zeisler was 59 when she had her first solo exhibition at the Chicago Public Library, the same year as Tawney’s Staten Island show. Before her studies, Zeisler collected paintings by Klee and Pablo Picasso, amongst others, as well as tribal art including Andean textiles. She later said that, like Tawney, though she studied the techniques of Peruvian weaving, the patterns did not interest her at all.4 Instead, her knotted, vibrantly hued fibre sculptures (often bright red) shared much with the Postminimalism of artists such as Eva Hesse.

Sometimes, the legacy of Bauhaus education took even more circuitous routes to arrive in the US. Trude Guermonprez was a German textile artist who trained in the early 1930s, first under the Bauhaus weaver Benita Koch Otte in Halle and then with the Bauhaus sculptor Gerhard Marcks in Berlin. She elected to stay in Germany during the war, despite her parents’ choice to emigrate to North Carolina, where her father, a musicologist, took a teaching position at Black Mountain College. In 1947, Guermonprez joined her family in America, covering for Anni during a sabbatical. In 1949, she was invited by another of her former teachers, the Bauhaus potter Marguerite Wildenhain, to help found a progressive new art school in Guerneville, California, called Pond Farm, which was based on Bauhaus principles.

In California, a separate branch of Fibre Art was flourishing. While Anni was making some of her finest work in relative obscurity at Black Mountain College in the early 1940s, textile artists on the West Coast were benefitting from the region’s thriving craft scenes and developed design industry. At that time, the most famous weaver and textile designer in the US was Dorothy Liebes, who had set up her studio in San Francisco in 1937. By 1938, she was employing 17 people and, soon, her client list included architects Edward Durell Stone and Frank Lloyd Wright. Liebes was unusual in that, before weaving, she had studied anthropology at the University of California, Berkeley — an institution with one of the country’s most significant collections of pre-Columbian textiles.

At the turn of the century — following his work for the Berlin Museum für Völkerkunde and, later, for the Penn Museum in Philadelphia — Uhle was recruited by the philanthropist Phoebe Hearst (mother of William Randolph Hearst) on behalf of Berkeley. It was under Hearst’s patronage that Uhle did some of his most important work, in particular excavating the Peruvian temple and burial site of Pachacamac. The treasures he found there were sent back to the anthropology museum in Berkeley, founded in 1901 by Hearst as an American counterpart to the Museum für Völkerkunde in Berlin.

Art students at Berkeley, therefore, enjoyed rare access to pre-Columbian art and textiles — an emphasis that was encouraged by the head of the Decorative Arts School, a weaver and anthropologist named Lila M. O’Neale. When she began to teach, following her Ph.D. in Peruvian textiles in 1932, her post was in the Department of Household Art, an almost entirely female section of the School of Agriculture. O’Neale fought for an expanded curriculum that included architecture, anthropology, art and art history and, in 1939, the name was changed to the Decorative Arts Department and relocated within the College of Letters and Science. In 1950, Berkeley was still the only university in the country offering a masters degree in textile art. Ed Rossbach, who came to be recognized as a maverick of the Fibre Art movement in the 1960s and ’70s, taught there for nearly 30 years until his retirement in 1979. For Rossbach, it was the Hearst Museum’s holdings of pre-Columbian basketry that were especially impactful, an influence that he sometimes overlaid with Pop imagery featuring Mickey Mouse or John Travolta.

Over time, as in the work of Tawney and Zeisler, pre-Columbian techniques and designs became just one of many sources shaping contemporary Fibre Art. The knotted panels made by Diane Itter, for instance, who graduated from the University of Pittsburgh in the late 1960s, relate as often to Andean art (as with Peruvian Fields, 1985) as to Amish quilts or Op artists such as Victor Vasarely. The Colombian artist Olga de Amaral studied at Cranbrook Academy of Art, Michigan — historically a centre for technical crafts education in the US — in the mid 1950s. When she returned to Colombia in the 1960s, she took with her an awareness of the nascent Fibre Art movement — and its relation to contemporary Western sculpture — and adapted it to her own cultural heritage, notably the pre-Columbian use of gold, which remains a prominent medium in her weavings.

The Czechoslovakian-born artist Neda Al-Hilali moved to Los Angeles in 1961. She travelled widely throughout her career, so textile traditions from Afghanistan, Iraq and Japan mingle in her work with those from Guatemala and Mexico. To work with textiles, Al-Hilali has claimed, is to be part of ‘a long chain of needle workers and weavers that goes back through the ages’.⁵ She is lucky, she says, to have lived through a place and time — California in the 1970s — that was uniquely receptive to experimentation in a field steeped in tradition. For her, as for other Modernist artists working with techniques mastered over two millennia ago, innovation required a respect for the past combined with the foresight to apply ancient knowledge to a future that was perpetually under negotiation.

1 Jennifer Higgie, ‘Fibre is My Alphabet’, interview with Sheila Hicks, frieze, issue 169, March 2015

2 Nina Stritzer-Levine, ed., Sheila Hicks, Weaving as Metaphor, Yale University Press, New Haven and London, p.47

3 Nancy Princenthal, Agnes Martin, Her Life and Art, Thames and Hudson, London, p.75

4 Oral history interview with Claire Zeisler, June 1981, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution

5 Oral history interview with Neda Al-Hilali, 18–19 July 2006, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution