What Ray Johnson Can Teach Us about a Good Postal Service

‘Frog Pond Splash’, published 20 November by Siglio Press, presents four decades of the artist’s mail-art exchanges with poet William S. Wilson

‘Frog Pond Splash’, published 20 November by Siglio Press, presents four decades of the artist’s mail-art exchanges with poet William S. Wilson

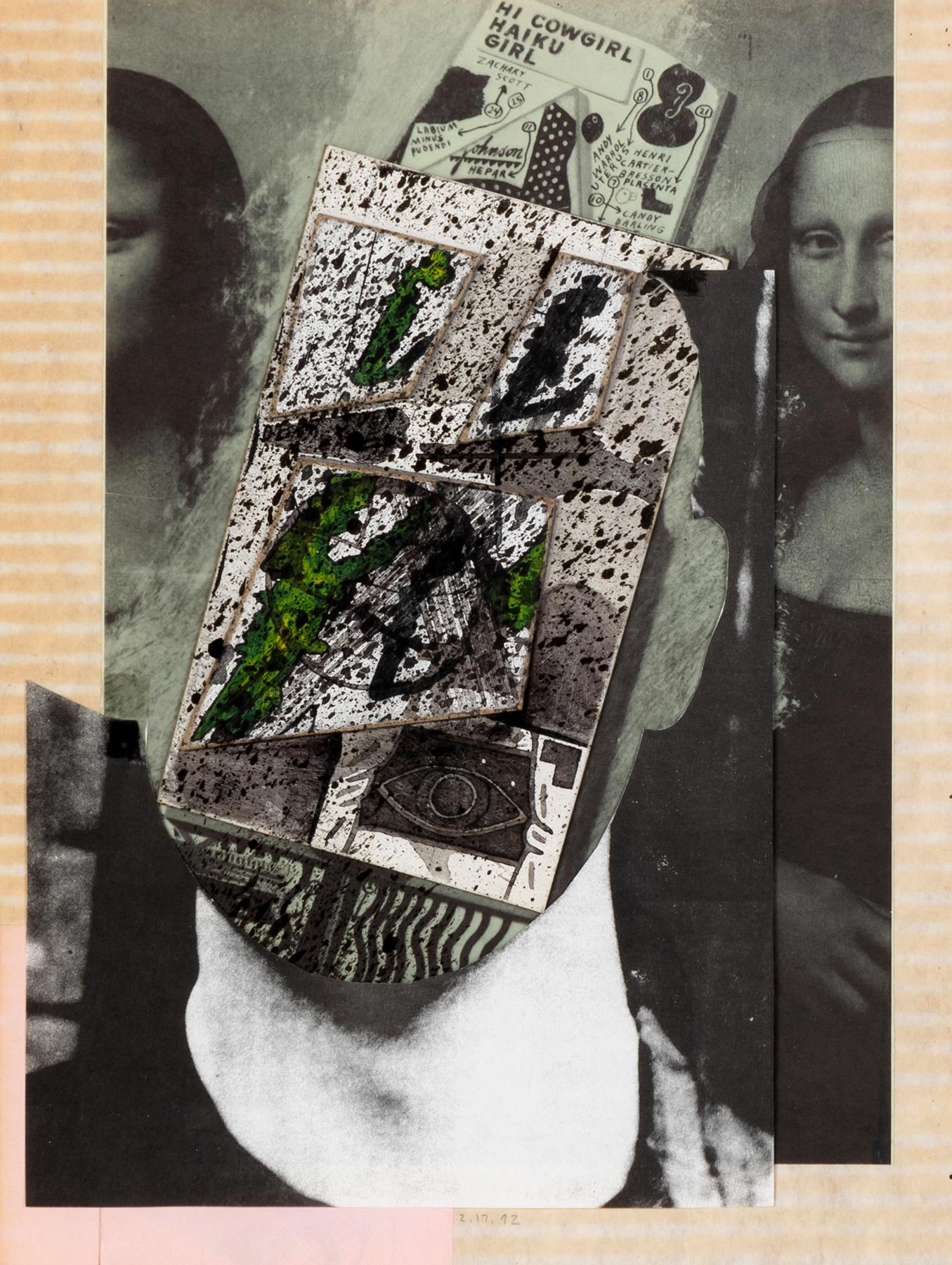

From his early studies at Black Mountain College in the late 1940s to his untimely death by suicide in 1995, Ray Johnson had an intuitive understanding of the latent potential for communication that could be uncovered once easy comprehension was bracketed in favour of playful chance encounters and associative logics. Buoyed by a circle of fellow artists, poets and co-conspirators in downtown New York – that included Lynda Benglis, Joseph Cornell, Willem de Kooning and Andy Warhol – Johnson, a painter and poet attuned to both avant-garde and pop culture, digested the zeitgeist for his own creative output. Best known today for his vertiginous collage works made from film magazines and newspapers, as well as his innovative system of mail art – a network of artistic and epistolary exchange he dubbed the ‘New York Correspondence School’ – Johnson illuminated relations between the verbal, visual and processual.

If Johnson’s creative bravura was defined by his willingness to cede meaning, significance and magic to the fragment and all its potential for becoming whole, his best interlocutor and biographer, the writer and poet William S. Wilson, is distinguished by his remarkable ability to keep apace. Frog Pond Splash, edited by Elizabeth Zuba and scheduled for release by Siglio Press on 20 November, presents a selection of Johnson’s collage works across four decades, placing them alongside excerpts of Wilson’s writings on Johnson, including essays, letters and emails that Wilson wrote to his friends until his death in 2016. In modelling the techniques of Johnson’s associative and collaborative methods, shot through with Wilson’s astute, probing writing, the handsomely bound volume furnishes an understanding of the deep artistic rapport that the pair sustained over more than 40 years of friendship. With Wilson, as with his other interlocutors, distance was often the defining metric for Johnson, who relocated permanently to Long Island but maintained his relationship to his creative milieu through correspondence.

In Frog Pond Splash, the juxtapositions between Wilson’s writings and Johnson’s collages function not didactically but in parataxis, which re-structures the reading and viewing process. As Zuba writes in her afterword, the collection intentionally includes unpublished emails and texts ‘to extend and refract the collages’ – which are arranged by visual relationships to the text, rather than chronologically – as ‘multiples, pairs or parts of a whole’. One such collage by Johnson – a 1992–93 silhouette of Lou Reed superimposed with a frog – appears across an excerpt from A Book about a Book about Death (2009), which Wilson wrote in response to Johnson’s ‘A Book about Death’: a collection of 13 printed collages, made between 1963 and 1965, and mailed to friends as separate pages. In this new context, Wilson’s essay functions as metacommentary on Johnson’s work. Johnson saw incompleteness as a kind of ethics, writing to Wilson of his faith in ‘the truth of objects and events under construction in this incomplete existence, wherein we don’t know the purposes which will be served by anything we do’.

Johnson’s mode of sustained correspondence and the strength of the relationships it fostered is yet another kind of ethics, one that, as Zuba writes in the book’s afterward, ‘permits urgent immediacies and suspends determination’. Awaiting the arrival of Frog Pond Splash in the post – an institution whose fate has been jeopardized by the fascistic current US President – I pored over the letters Wilson had archived online. ‘The first principle of Ray’s art is that anything isolated is beautiful, albeit opaque,’ wrote Wilson in his introduction to Johnson’s 1965 book, The Paper Snake. ‘The second principle is that meaning awakens in that isolated beautiful thing when it is juxtaposed to something like it.’ Reading of this kind, with generosity and commitment, is a powerful social act, and it is a gift to share in such an intimate balance of criticism and care.

Main image: Ray Johnson, Untitled (Dorothea Lamourstuvwxyz) (detail), 1980-81-82-93, published in Frog Pond Splash. Collages By Ray Johnson with texts by William S. Wilson, Siglio Press, 2020.Courtesy: The Ray Johnson Estate