Wicked! Modern Art’s Interest in the Occult

Contemporary art’s resurgence of interest in magic has a powerful art-historical precedent

Contemporary art’s resurgence of interest in magic has a powerful art-historical precedent

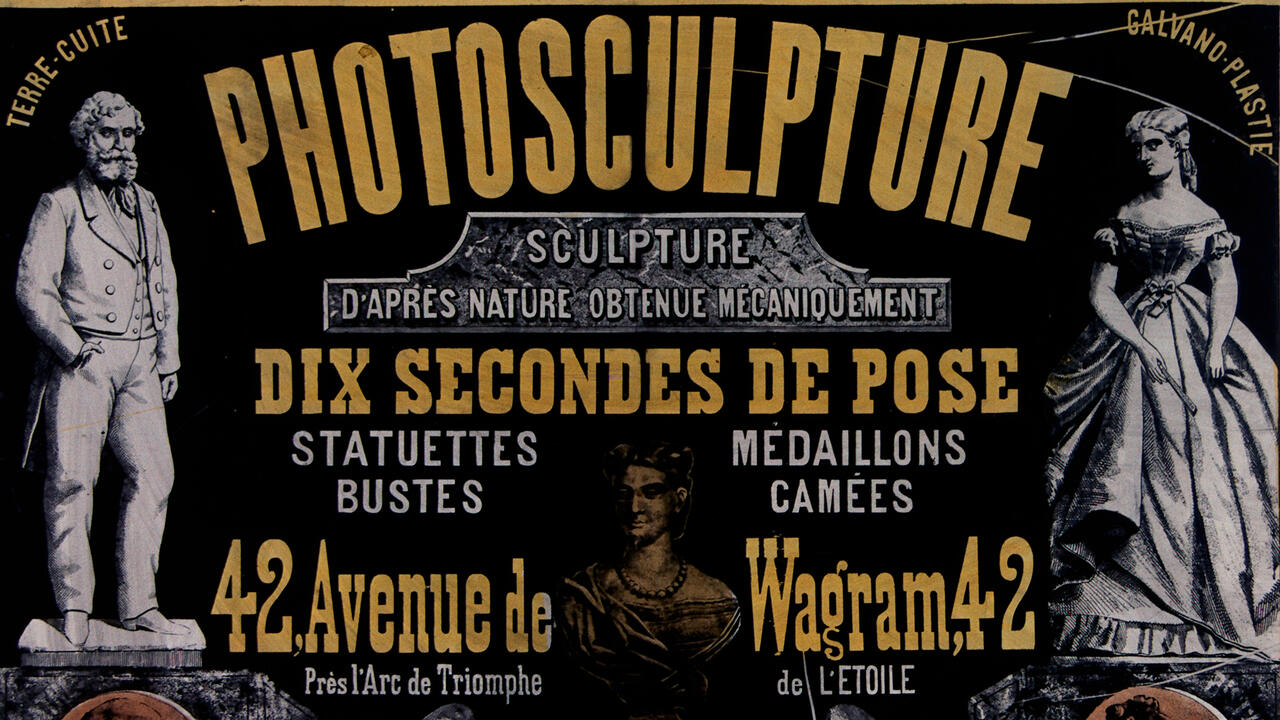

The resurgence of interest in magic today – in art, popular culture and ritual practices – is not without precedent: the occult has faded in and out of the cultural arena for more than a century, its seeds a feeling of lack and longing, from the development of Wicca after World War II to the esoteric counterculture of the 1960s. We can recognize this desire in our current moment – steeped in advanced capitalism, swift gentrification and right-wing political gains – in which magic holds the promise of connection and empowerment. It was also palpable in the 19th century, the setting of the first widespread occult revival since the Christianization of Europe, early-modern witch hunts and the so-called age of reason. It flourished in Europe, and France in particular, in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. We can trace many current magical practices back to this time, from an occult use of the tarot to neopagan worship that identifies the triple goddess with the phases of the moon. Modern art, psychology and feminism also have their roots in this period, along with the monumental socio-economic effects of modernization. The face of Europe changed irrevocably: railways were vastly extended, suburbs sprouted factories and cities towered upwards, their narrow streets expanding into boulevards. Positivist science also ascended through these conditions, bolstered by the quick development and profitability of new industrial technologies. Yet, the dark side of technological progress is often disillusionment, and it is in this sense of longing and decay that we can trace the beginnings of the belle-époque occult revival.

Like so many facets of modern life, the first seeds were sown during the 1789–99 French Revolution. Unleashing bloodshed and terror in the name of reason, its idealism soaring to hysterical heights, the revolution undermined its own guiding principles. The hegemony of rationalism – so central to European thought since the Enlightenment – was further eroded in subsequent decades, in a climate of conflict and unrest that saw the Napoleonic wars of 1803–15, the revolutions of 1830 and 1848, and the short-lived, brutally supressed Paris Commune, an insurgent government that ruled from 18 March to 28 May 1871. (This thread of dissent would be taken up by the Dadaists in the 20th century, in response to the atrocities of World War I.) Traditional Christianity, too, was in profound crisis. Its worldview – circumscribed to binaries of good and evil, spirit and body, culture and nature – was increasingly seen as overly simplistic in the context of a complex, tumultuous universe.

The renewed interest in occultism was driven by a search for alternatives and origins, for a world that holds both chaos and coherence, its rhymes echoing through dimensions, its rhythms hinting at key truths. Movements that were founded in the 19th century, or which saw an upsurge in popularity, include Theosophy, Rosicrucianism, Martinism, Freemasonry, Gnosticism and neo-Catharism as well as local groups such as London’s Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn. In art and literature, these ideas were taken up by the Symbolists: a loosely affiliated, international movement that flourished from the 1880s to the 1910s, particularly in Paris. Symbolist artists were not active practitioners of magic; their interest was rather in evoking the spiritual – an elusive notion, perennially difficult to define, which was understood in contrast to the prevailing materialism of the time. In this sense, the movement can be seen, in part, as a reaction to Impressionism, whose concerns were more formal, based on fleeting sensory impressions and grounded in everyday life. (Which is not to say that they were superficial: see Berthe Morisot’s incisive portraits of her sister Edna and Mary Cassatt’s studies of child subjectivity.)

For the Symbolists, esoteric knowledge was a means of accessing the scope of the mind and the quintessence beyond appearances. And fin-de-siècle Paris had no shortage of material: Edmond Bailly’s Librairie de l’art indépendant (Bookshop of Independent Art), established in 1888, became a central meeting point for Symbolist artists and writers and for the discussion of occult topics, while Lucien Chamuel’s Librairie du merveilleux (Bookshop of the Marvellous) was popular with mystics and scholars. Theosophy was particularly influential. Founded by Helena Petrovna Blavatsky and her colleagues in New York in 1875, the Theosophical Society aimed to distil common elements from the world’s religions and esoteric traditions and establish an essential, universal understanding. The idea of fundamental principles that could bridge East and West, Christ and the Buddha, was immensely attractive to a number of artists – particularly in a context of colonial expansion, which aroused interest in similarities as well as in differences. The artist Odilon Redon was amongst those who frequented Bailly’s bookshop. Engaged in Theosophy – particularly Édouard Schuré’s comparative studies of religious prophets – as well as Buddhist and Indian philosophy, Redon realized numerous depictions of religious figures that evade traditional iconography and narratives. He focused instead on themes of light, death and introspection, as in The Death of Buddha (c.1899) and The Sacred Heart (The Buddha) (c.1906), which was closely based on an 1895 drawing the artist had made of Christ and then renamed.

It is interesting to note that both Symbolism and Theosophy claimed an affinity with science. While they rejected the sway of strict positivism – founded on observation and quantifiable evidence – they believed that the spiritual was one part of a definite truth and that their investigations chimed with a more encompassing science. Indeed, as Nadia Choucha writes in Surrealism & the Occult (1991), occultists often looked to scientific discoveries as proof of their own beliefs. Thus, the fourth dimension, first described by Charles Howard Hinton in his 1880 article ‘What Is the Fourth Dimension?’, supported the idea of the astral plane, while 20th-century physicists corroborated an understanding of the universe as fundamentally fluid and chaotic – from Albert Einstein’s theory of relativity to Werner Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle and Henri Bergson’s writings on multiple planes and the limits of sensory perception. Evolution and the search for biological origins, which occupied scientists from the 1860s onwards, also inspired both occultists and artists – not as a sterile process of natural selection, but as a font of endless variety and wonder, which speaks to the creative energies at the foundations of life. We can read Redon’s self-described ‘monsters’ in this light, most explicitly in ‘Origins’, a lithographic series from 1883. These creatures explore the fantastical possibilities of life’s genetic code, stemming from the artist’s studies of comparative anatomy and embryology, as well as from his close friendship with the plant physiologist Armand Clavaud, whose research on algae, Redon notes in ‘Artist’s Secrets’ (1913), ‘searched […] at the edge of the imperceptible world, for that life which lies between plant and animal’.1 In one image from ‘Origins’, a flower gazes upwards, plush lashes forming petals, its pistil a round, open eye (Was It Upon a Flower That Nature First Attempted to Bestow Sight?). Spirit of the Forest (1890) also explores the rhymes between plant and human life: its skeletal form crackles with vitality, as roots extend from its knotted leg bones and branches sprout from the base of its head (the location of the cerebellum chakra, or ‘well of dreams’, in Tantric thought).

Redon’s monsters underline a key idea in the history of art and magic: that the most original, compelling works often look to our foundations, rather than lofty, distant truths. While Symbolist art was frequently dismissed as being escapist and overly literary – and largely still is today – its focus on the dark, irrational aspects of our nature profoundly influenced the course of modern art, informing Surrealism in particular. (This interest was later echoed by Sigmund Freud, who would investigate the psychological drives and aberrations beyond social conditioning in his 1905 book, Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality.) A crucial source for these artists, and indeed for many modern ideas on magic, were the theories of the French occultist Éliphas Lévi, who emphasized the essential unity of opposites: of light and dark, positive and negative, masculine and feminine. In the frontispiece to his 1854–56 Dogma and Ritual of High Magic, Lévi illustrated this notion in an image of the deity Baphomet: an androgynous figure, both animal and human, winged and hoofed, which points towards the white moon of Chesed (mercy) and the black moon of Geburah (justice or severity).2 That Lévi’s Baphomet was widely misidentified as the Christian Devil speaks to the prevalence of a rigidly dualistic worldview. His idea went hand in hand with a renewed interest in archaic paganism, particularly in the creative and destructive energies of ancient Greek and Roman goddesses. Marvellous, elemental, indifferent to death, joy and suffering, the idea of daemonic power was the most potent opposition to a rational, materialist order; as Celia Rabinovitch writes in Surrealism and the Sacred (2002): ‘With its connections to energy and eros, [the daemonic] remained the most subversive element of archaic thought that had survived throughout Western intellectual history.’3

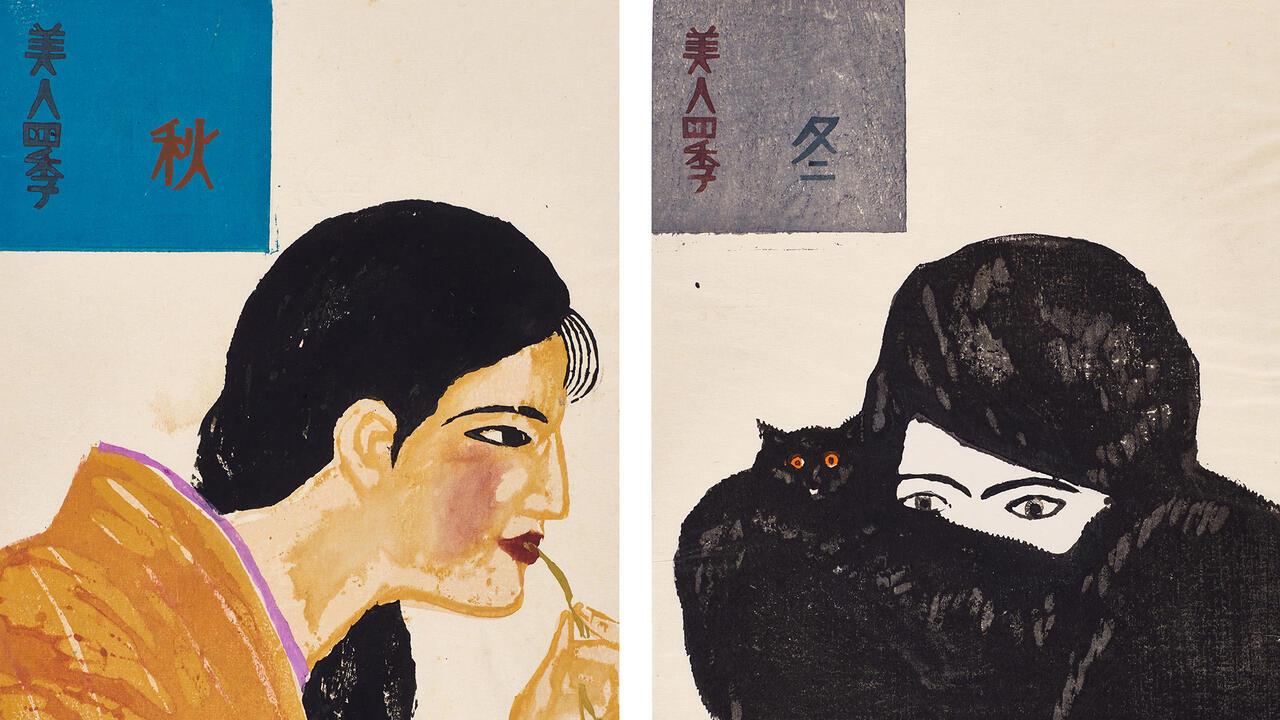

That such a concept of the goddess would undergird a new, more complex understanding of femininity is one of the most enduring and fascinating legacies of the 19th-century occult revival. Of course, this renewed archetype was very much of its time, emerging as an antidote to the rigidity and decay of an industrial, patriarchal society and mired in the anxieties of this context. This ambivalence is palpable in the works of numerous Symbolist artists and, indeed, these images are widely credited with having introduced the figure of the femme fatale. Often appearing as a powerful, mythical figure or a hybrid creature such as the sphinx, harpy or chimera – itself a manifestation of mutable, chthonic power – the femme fatale intertwines death and sexuality, invoking our most immediate impressions of destruction and creation. Fernand Khnopff’s painting The Caresses (1896) belongs to this repertoire: an image of affection and obsession, in which the sphinx embraces an androgynous Oedipus, her indulgent expression at odds with her tensed, possessive bearing. The erotic, commanding female figure also appears in several works by Gustave Moreau, whose 1864 Oedipus and the Sphinx inspired Khnopff’s canvas. Moreau’s The Apparition (1876–77) is one of the most recognizable images of the femme fatale, depicting a semi-nude, bejewelled Salome conjuring the gruesome head of John the Baptist, the rich, red tones of his encrusted, streaming blood echoed in her sumptuous robe.

Such images are, ultimately, indicative of women’s emancipation: an insistent topic by the mid-19th century, which saw the first wave of feminism. And, certainly, the resounding tone of a revived interest in the figure of the goddess – in the 19th century and today – is one of empowerment. That Symbolist artists were overwhelmingly male is a curious point, given that women were central to the occult revival, from Blavatsky to the influential women of the Golden Dawn and female mediums. (It should be noted that Impressionism, which was contemporaneous with Symbolism, was a gender-equal movement.) Representations by women that engage with the occult and the chthonic are more readily found amongst the Surrealists, who were deeply influenced by Symbolism. Whereas artists such as Khnopff and Moreau drew on established iconographies, the Surrealists created new mythologies, linking primordial energies to the creativity of the unconscious. In André Breton’s writings, notably Nadja (1928), woman represents this force through her connection to procreation, dreams and the underworld. For the female artists associated with Surrealism, this ideal was no doubt a burden, stifling them with the laurels of the muse. Yet, in their own art, occultism stimulated novel explorations of nature, creation and subjectivity. These works do not tend towards a facile identification of womanhood with creative power. Méret Oppenheim’s The Green Spectator (One Who Watches While Someone Dies) (1933/59), for instance, portrays nature as a dispassionate, cyclical force, its pared-down, columnar form both human and snake-like, its materials – copper and wood painted to resemble serpentine – signalling its primal origins: the underground world of the serpent.4

For Leonora Carrington, occultism inspired a penetrating personal iconography that is formally brilliant. The artist was fascinated by Celtic mythology, the folklore of Mexico (where she settled in 1942, after fleeing Europe) and modern occult theory, notably Robert Graves’s 1948 book-length essay on myths, ‘The White Goddess’ – ‘the greatest revelation of my life’5 – which articulated the Celtic triple goddess as Maiden, Mother and Crone: ‘The New Moon is the white goddess of birth and growth; the Full Moon, the red goddess of love and battle; the Old Moon, the black goddess of death and divination.’ In Carrington’s painting The House Opposite (1945), the three goddesses tend the cauldron of a sprawling, cosmic home: a metaphor for life and the self, with each space a threshold to the next. Their hearth sits in the underworld, a sapphire spring and two egg-shaped chickens at their feet: symbols of the alchemical egg, the prima materia at the origin of life. Death visits the room above, sucking out the soul of a supine figure, while, in the next space, a woman sits bolt upright in bed, as if waking from a nightmare. Memory and dream reside in the water-filled glade below, where a woman sobs beside a rocking horse – a recurring image in Carrington’s work, recalling a toy from her lonely, restricted childhood. The creature is unbridled in the dining hall, where a woman eats at the table, her white hair resembling a mane, her shadow a horse. Perhaps she is Rhiannon, the Celtic lunar goddess of art, transformation and rebirth. A woman who found an affinity between the studio, kitchen and alchemical laboratory, Carrington uses the home as a metaphor for magical thinking, uniting decay and regeneration, life and the imagination.

This article first appeared in Frieze Masters issue 8 with the headline ‘The Other Side’.

Main image: Leonora Carrington, The House Opposite (detail), 1945, tempera on board, 33 × 82 cm. Courtesy: West Dean College of Arts and Conservation

1 Barbara Larson, ‘Evolution and Degeneration in the Early Work of Odilon Redon’, Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 2:1, spring 2003, https://bit.ly/2XhcA3C, accessed 15 May 2019

2 Tobias Churton, Occult Paris: The Lost Magic of the Belle Époque, 2016, Inner Traditions, Rochester, p. 96

3 Celia Rabinovitch, Surrealism and the Sacred: Power, Eros and the Occult in Modern Art, 2002, Westview Press, Boulder, p. 203

4 Ibid., p. 195

5 Susan L. Aberth, Leonora Carrington: Surrealism, Alchemy and Art, 2004, Lund Humphries, London, p. 79