Wolfgang Tillmans’s Ways of Seeing

Jeremy Atherton Lin profiles the German photographer and reflects on the artist’s lifelong search for the truth

Jeremy Atherton Lin profiles the German photographer and reflects on the artist’s lifelong search for the truth

Wolfgang Tillmans is half-rotating on a swivel chair in his Berlin studio. It’s one of the many ways the artist thinks with his body. He’s wearing a baggy white T-shirt printed with luminescent feathers by artist Anders Clausen, the cover art of Spoken By The Other, an EP released by Tillmans and producer Oscar Powell in 2018. The roomy sleeves provide burrows for Tillmans’s restless hands. In other moments, he brings his palms together, as if in gratitude, or points in zigzags, drawing connections in the air.

‘I somehow have this sense of history – of the now being history,’ Tillmans says. ‘And of the history of now being possibly rewritten at any time.’ This notion has permeated the artist’s work for three decades. It’s present in truth study center (2005–ongoing): rectangular tables on which news articles, scientific reports and Tillmans’s own photographs are neatly configured under glass. The evolving project contemplates how society produces, contains and abandons facts, what Hannah Arendt called ‘fragile things’ in her 1967 New Yorker article ‘Truth and Politics’. In a recent iteration of truth study center at Art Twenty One in Lagos, Nigeria – from where Tillmans has just returned, after installing the show – a printout of a Guardian article on microplastics found in human lungs was displayed near two plastic wrappers from Itsu zen’water bottles.

The title ‘truth study center’, Tillmans explains, was always ‘absurd, an impossibility’. Growing up gay, in ‘discord’ with convention, meant he was ‘naturally vaccinated against any pretensions of purity’. He soon learned ‘that there are two ways of looking at things’. Tillmans began using the alias Fragile when he started making music as a teenager. He tells me that by the time he had reached the age of 14, in 1982 – ‘before I was gay, even’ – he was acutely aware of the AIDS epidemic. Alongside his fascination with astronomy, he began to collect articles about the disease from the Frankfurter Allgemeine. This unusual interest was driven by an admixture of scientific curiosity and intuition. ‘I somehow felt this was relevant,’ he remembers, ‘this idea of a virus attacking the very cells that are there to protect you. I felt it was a significant image.’

His ambiguous phrasing reveals the mindset of a young person developing into an artist. The quest for ‘a significant image’ persists in his studio today, where printouts are taped to one wall, and a still-life photo of a burgundy clover has been ‘test hung’ opposite. In another of his contemplative gestures, Tillmans holds his fingers in a bowl shape, open and teacherly, as though some vulnerable truth were cradled in the palm of his hand. Early in our conversation, we lost ourselves in a discussion of the rapid advance to encoding billions of transistors on a single microchip, a marvel Tillmans alludes to in his vocal piece, I want to make a film (2018). But where, I asked, does the technological meet the poetic? ‘I guess that’s very much describing what I try to get at,’ he responded. ‘I obviously don’t have an answer, but I have a humble but somehow vibrant feeling for the significance.’

This month, the artist’s retrospective ‘To look without fear’ opens at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. There are 18 truth study center tables planned, around half of which are from the work’s iteration at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, in 2006. ‘At that time, of course,’ Tillmans remarks, ‘the title didn’t have much resonance. Surrounded by claims of absolute truth in the early 2000s, strongly moved to do this work, I had no idea that ten, 12 years later, this would be totally the focus of world politics.’

Now the challenge is what to install in the era of truthiness and truthers and Trump Media’s Truth Social app. ‘How do I deal with that?’ Tillmans asks. ‘Obviously, I don’t want to continue the cacophony that is all around us.’ This prompts me to ask if he ever meditates, which I then rephrase as striving for quietude. ‘It’s funny,’ Tillmans laughs. ‘You went quiet after you said the word “meditate”. And I immediately thought of [the philosopher Jiddu] Krishnamurti, who resolved this whole subject of meditation for me when he said forget the symbols of the gesture, of authority. Know there is no sacred action. If you look at a flower and just let it be itself and fully understand and respect it as it is, that is meditation. That was a huge weight off my shoulders,’ he says, tapping his collarbone, ‘because I felt, OK, I am able to meditate. Even though I am often working a lot and under some pressure, the good thing is that, in the morning I can wake up and look out of the window and have the most in-the-moment experience, which,’ he laughs, ‘doesn’t exactly last forever during the day.’

In the moment of looking out the window, I ask, does he ever not want to take a picture? ‘That, I think, is the crux, or the essence, of what I negotiate,’ he replies. ‘It’s extremely close to the very core of my practice. How can I be in the here and now and at the same time, take a picture? And that pivots within me without much conflict. I think that allows me to be who I am and do what I do. I am able to be there. And that’s the incredible thing, that this is a meditation. It can be a glimpse or one intense look.’

Over the years, moving through overlapping social scenes, I have looked at Tillmans looking. I’ve seen him scan a group of smokers on the pavement outside a gallery opening in Manhattan and photograph a napkin on the sticky bar at the now-closed Joiners Arms pub in East London. In each case, he grinned as he observed – as if his radiant countenance were a camera flash. ‘But what’s super important,’ he insists, is that ‘the intention, the desire to make more, cannot come between being with a person, being in a space. If the purpose of looking is only to make, then there’s nothing to look at.’ In turn, Tillmans has looked at me looking. Before we were formally introduced, we locked eyes on a Friday evening in the middle of the run of his show ‘2017’ at the Tate Modern. I was startled by his presence, but it seemed somehow true to his practice to return to the gallery and see visitors engaging.

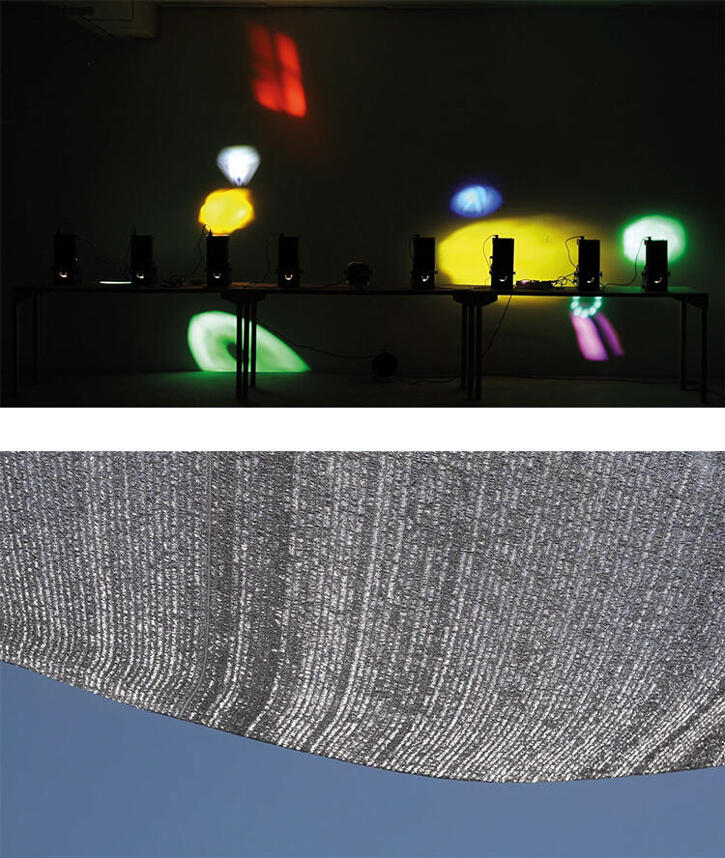

Tillmans has made clear he does not intend to construct narratives in his work. His images are not there to suggest what occurred before and after. Over the years, I learned to stop interpreting discarded or clinging garments in works such as grey jeans over stair post (1991) or Shiny shorts (2002) as costumes in a striptease or props in foreplay. Instead, I’ve come to really see the surfaces, to behold the folds of fabric. Now I sense that for Tillmans, conversation is likewise about making sparks rather than settling into plot points. He’ll share something, then qualify that he’s ‘a little bit shy’ (his synonym for ‘reluctant’) about the topic becoming too much of ‘a story’. For instance, ‘Fragile’ (2018–22) – Tillmans’s Goethe Institute-sponsored exhibition that has toured to eight countries across the African continent – is a truly remarkable undertaking, but he’s generally evaded global media coverage, reserving interviews for local press instead. He was also compelled to ensure works in the exhibition – the sweaty nightclub close-ups in Chemistry Squares (1992); his out-of-camera ‘Silver Works’ (1992–ongoing) and sculptural series ‘paper drop’ (2001–ongoing); the 2016 portrait of wet Frank Ocean; the landmark Lutz & Alex sitting in the trees (1992) – moved directly between venues without shipping to Europe and back, a small challenge to what Tillmans describes as ‘the absurdity’ of outdated colonial transport routes.

‘Fragile’ arrived in Accra in October 2021, just as the country’s parliament began to debate The Promotion of Proper Human Sexual Rights and Ghanaian Family Values Bill, a piece of legislation seeking to outlaw not just queer sex but related organizations and allyship. ‘It was bizarre, in Accra, to have this on morning television and being discussed openly in the most derogatory, prejudiced way,’ Tillmans says. ‘And to see the all-pervasive display of Christianity, of private preachers, just like businessmen, advertising their church and their path to salvation. And just how fraudulent the whole thing is.’

Under the proposed legislation, someone who ‘promotes or supports’ queer identities (in the bill’s expansive terminology, LGBTTQQIAAP+) could be jailed for up to ten years. In an interview on the BBC World Service on 26th October 2021, Ghanaian MP Sam George hauled out the old cliché: ‘God created Adam and Eve, not Adam and Steve.’ Religious leaders in the UK, including the Archbishop of Canterbury, voiced their concern over the draft bill – a painful irony considering that ‘buggery’ was criminalized in Ghana under British law, via the colonial application of the Offences Against the Person Act of 1861.

I ask Tillmans whether such conditions prompt self-censorship. ‘I guess one can call it self-censorship, but one can also call it consideration,’ he replies, then describes his selection process: ‘Is this too obvious? Is this too pleasing? Is this too controversial? Is this too flat? Or is this just right?’ To Tillmans and his team, ‘it was clear, of course, that we are not there to create a scandal. And I feel confident that I can show my way of looking at humans without showing nudity or genitals.’ No nudity? I ask. ‘Well, there is, like, Anders pulling splinter from his foot (2004). But there are no genitals.’

In 2018, at a press meet-and-greet on the morning of the opening of the first ‘Fragile’ exhibition at the Musée d’Art Contemporain et Multimédias in Kinshasa, journalists seemed primarily interested in Tillmans’s political activism. He initially attempted to placate them with only general impressions in the wake of his high-profile anti-Brexit campaign. ‘They kept asking again. And then, even though I was told not to, I just said, “You know, really, I owe the freedom to live the way I live now, and love the way I love, to generations of other activists, who did things in the past, who spoke out. And, to me, as a gay man, I have this very personal access to knowing that activism has changed things for the better for people like me.” And then there was silence in the room.’ He guffaws, still palpably relieved to be out of that particular spotlight.

The political situation in each country ‘Fragile’ toured is different, of course. While the post-Apartheid South African constitution enshrines the legal right to same-sex marriage, in Lagos, Tillmans encountered ‘one of the only few “out” people in Nigeria,’ a lone citizen who has taken to marching the streets carrying a protest sign, risking years of imprisonment. ‘I asked him, “Yeah, but, is visibility not antagonising people?” And he said, “No. You have to do it.”’ Two days later, at the artist talk for ‘Fragile’, Tillmans found himself being ‘quite outspoken about civil rights, and that gay rights and women’s rights are human rights’. This time, the audience appeared sympathetic and afterwards nearly everyone in attendance – gallery technicians, students – approached him to take selfies.

Near the end of our conversation, I read aloud two sentences that Tillmans wrote 30 years ago. They comprise his brief but impassioned response to London’s Gay Pride in 1992, published in i-D magazine. At the time, AIDS was highly stigmatized and antiretroviral combination therapy not yet available to people with HIV. Tillmans wrote, ‘I’m fucking angry and I don’t want this to kill me and I don’t want it to make me go insane. I want to survive and I want to be happy.’

After reading these lines, I ask how he’s doing now, and tell him he seems happy. ‘Yes,’ he grins, perhaps equivocally. ‘I guess I was also a happy person, most of the time, then. But I remember life in the early ’90s, for me, was a flip-flopping. A constant, yes, happiness, but there could always be a dark mood, a fear, a swollen lymph gland, something like a white layer on your tongue. Suddenly, the mind going: is this candida, an onset of AIDS? But one also didn’t necessarily want to know. Why would you?’

It’s been gradually dawning on me that when Tillmans expresses wariness of a given subject becoming a ‘story’, what he’s suspicious of may be the way grand narratives can stifle and contain. In this way, ‘story’ distracts from that which he strives to inhabit and convey: fleeting, significant states of being. The immense personal loss Tillmans suffered due to the AIDS virus and the consequences of his own HIV diagnosis in 1997 have been written about elsewhere. He said enough when he told a Dazed journalist in 2017: ‘I’m aware of the fragility of life.’

Tillmans also chose Fragile as the name of his record label, on which he recently released a full-length album, Moon in Earthlight (2021). It’s a spellbinding suite of loops, field recordings and fragmentary lyrics. The title derives from ‘Earthlight’, the name given to the diffuse reflection of sunlight from the Earth’s surface and clouds. Faintly illuminating the dark portion of the Moon during its waxing crescent phase, this creates a visual phenomenon sometimes described as ‘the old Moon cradled in the young Moon’s arms’.

On one of the tracks on Moon in Earthlight, ‘Possibility/Kardio Loop (a)’, Tillmans speaks over a warped sample of the audio output of an echocardiogram machine. He repeats a series of phrases: ‘The possibility of a happy life / The promise of a happy life / The hope for a happy life.’ It sounds like a voice memo recorded on the hoof; a car horn blares in the background. It’s as if Tillmans is attempting to help the words escape him, to self-select, reconfigure and find a formulation that most closely expresses this fundamental aspiration.

This article first appeared in frieze issue 229 with the headline ‘Wolfgang Tillmans’.

The exhibition ‘Wolfgang Tillmans: To look without fear’ is on view at the Museum of Modern Art, New York from 12 September 2022 to 1 January 2023

Main image: Wolfgang Tillmans, Paper Drop Novo, 2022. Courtesy: the artist, David Zwirner, Hong Kong/New York, Galerie Buchholz, Berlin/Cologne and Maureen Paley, London