Wu Tsang

Clifton Benevento, New York, USA

Clifton Benevento, New York, USA

Wu Tsang has always attended to the voice in its multiple valences, taking advantage of its ability to convey both an intimate, embodied presence and something more intricate and less authorial. The voice, after all, can be thrown or disguised, or used to imitate or channel. In Tsang’s performance work, the voice’s channelling power forms the basis of ‘full body quotation’, a technique in which the performer ‘re-speaks voices mimetically – not just the text but tone, breath, accent, idiom,’ according to the artist. Often employed as a pointedly self-aware means to represent those silenced and dispossessed, Tsang has used full body quotation to re-create the halting, computer-voiced speech from autism activist and writer Amanda Baggs’s video manifesto In My Language in his work Shape of a Right Statement (2008). Likewise, his project Full Body Quotation (2011) includes key lines of dialogue from participants in the much critiqued (and still very popular) ball culture documentary Paris is Burning (1990).

Accordingly, the voice was again the focus of Tsang’s second solo show at Clifton Benevento this September. The exhibition contained two video works and a pair of sculptures, the latter consisting of tan, diaphanous robes fringed with crystals and piled upon dress forms. Wearing a red velvet shawl reminiscent of the sculptures (crystals also featuring heavily in his outfit), his eyes and mouth adorned with makeup, poet and writer Fred Moten gesticulates joyously during Girl Talk (2015). Filmed in a sunlit garden, Moten whirls in slow motion to the trickle of a lion-headed water fixture and the acapella rendition of jazz standard ‘Girl Talk’ by singer Josiah Wise.

Carried by Wise’s starkly emotive voice, Girl Talk feels celebratory and pleasantly direct, especially in comparison with the two-channel Miss Communication and Mr:Re (2014). The latter work features a series of voicemail messages left by Tsang and Moten for each other over the course of two weeks. At the gallery, a screen displayed transcriptions of the messages, the two voices panned to either side. Playing simultaneously, the voicemails fall in and out of sync, making it difficult at times to catch more than fragments of what’s being said. Still, those details, however decontextualized, stick with the listener: Tsang describing ‘olive trees that stretch into the distance’, Moten intoning the word ‘doom’ over and over and fixating on the name of a UCLA cardiologist. The two also muse on the nature of comprehension itself, forming a meta-commentary that runs throughout the often opaque piece. Moten describes the ‘radical inability properly to present myself’; Tsang ponders the knight’s move in chess, that act of approaching something and then swerving to the side, and the nausea induced by straining for authenticity, as ‘every fibre of my being does not want to be authentic, does not want to embody who I’m supposed to be.’

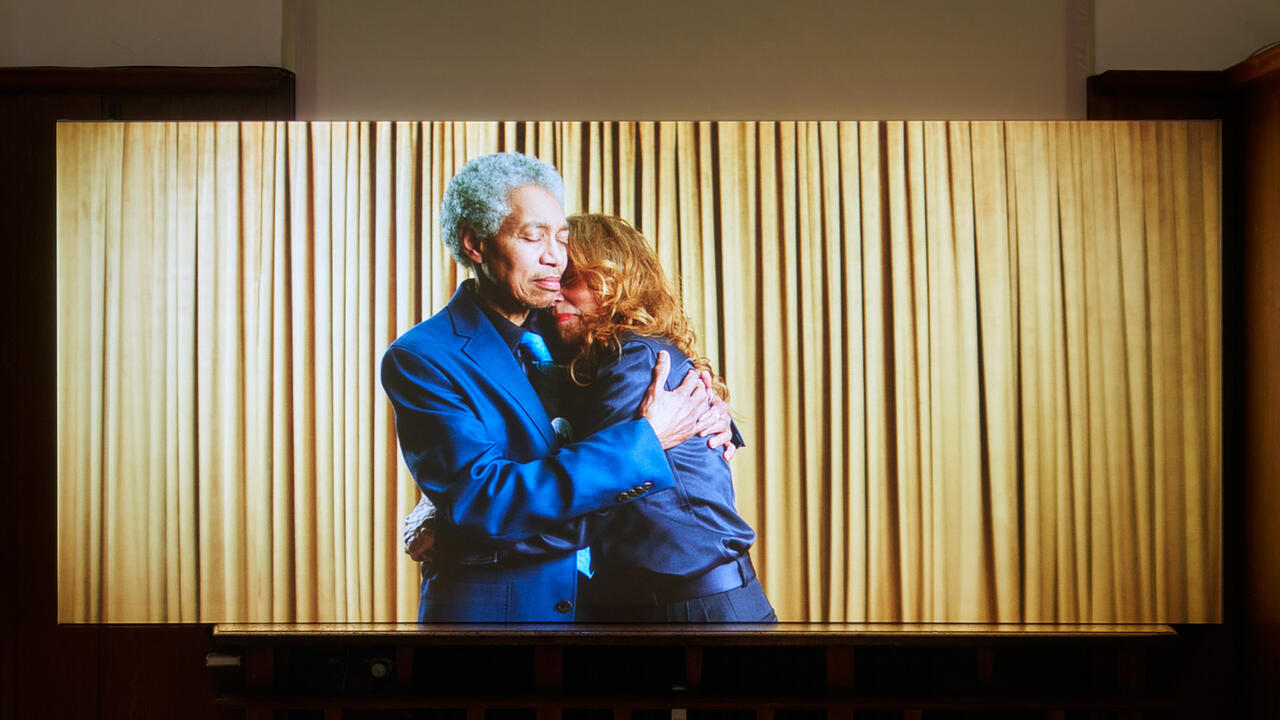

Given the intimate nature of voicemails, I first felt as though I was trespassing. Opposite the first screen, two monitors bear close-up shots of Tsang and Moten. The two look on silently, as if watching the visitor eavesdrop. Tsang seems on the brink of tears, while Moten squints slightly in what resembles mild, bemused disappointment. But then their faces change. Tsang begins to look almost giddily happy as Moten slyly smiles. They appear wearing lipstick. Moten gets up and turns his back to the camera, not seeming at all angry. As they slowly shift, their faces, like their voices, become inscrutable despite the intimacy of their presentation, easing any sense of judgement. By the end, I felt slightly embarrassed by the idea that I could trespass at all – as if hearing a voicemail or looking into someone’s eyes necessarily gave me access to some authentic interior world of being.