Yvonne Rainer

Raven Row, London, UK

Raven Row, London, UK

As someone cursed with the wayward gait of a drunk learning to ice-skate, I’m prone to thinking of dancers as a special, slightly frightening breed of magical creature, like the earthly descendants of certain birds. How, then, to make sense of Yvonne Rainer’s ‘Dance Works’, which sends me into this familiar state of baffled awe but depends on something other than exquisite technique? (It even permits a certain carefully rendered clumsiness.) Bruce Nauman’s contemporaneous and uncanny trapeze act, Walking in an Exaggerated Manner around the Perimeter of a Square (1967–68), is a much more useful guide here than the heart-fluttering theatrics of Swan Lake.

But maybe bewilderment is the desired response. This sprawling retrospective captured over a decade of radical experimentation stretching from 1961 to 1972, in which Rainer found the contours of her own enigmatic and slyly contorted form of choreography. In an inspired move, curator Catherine Wood juxtaposed a shifting sextet’s live recital of four pieces – two of them never before performed in Britain – with a programme of short films including various movement studies, recordings of rehearsals and Rainer’s first (and most ghostly) fiction film. It was a combination that illuminated the reticent strangeness of works half a century old then fully restored their modern shock. If at first its contents seemed thorny and hermetic, spun out of rhythms too maddeningly difficult to crack, then slow adjustment to its wavelengths revealed a mercurial, discreetly astonishing sort of art that encourages puzzlement, disorientation and awkwardness in the bodies of its dancers and the minds of its audience alike. There’s no obfuscating virtuosity here, only a set of riddling enquiries into dancing itself.

The biographical prelude to this run of game-changing pieces is rich with seductive detail. Rainer began circulating in New York’s subterranean art world in the mid-1950s as Minimalism and performance art took shape. She studied under Merce Cunningham and appeared in productions staged by the fascinating (and little-mentioned) choreographer James Waring that mixed camp hysteria, Noh-haunted ceremony and vaudevillian mischief. As Rainer recalls in her memoir Feelings Are Facts (2006), Waring ran a company of ‘misfits’: ‘too short or too fat or too uncoordinated or too mannered’ to dance elsewhere. That ‘misfit’ status is crucial to her work: the lissome body you see twisting on monitors throughout the exhibition is too oddly proportioned – ‘long back and short legs’ as Rainer writes – to meet the fairytale standards of classical ballet. Rejecting these factual trappings, ‘Dance Works’ presented the figure twirling alone, which is at once smart and risky, remaking her as an out-of-nowhere, avant-garde siren.

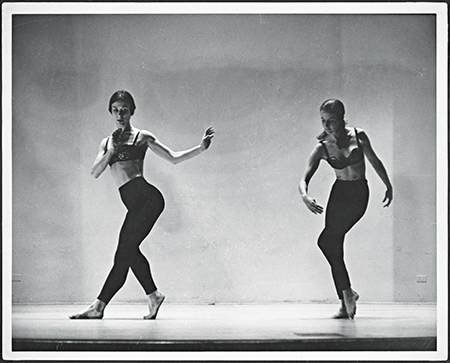

Diagonal (1963) is a dense and playful piece that refuses to coalesce but tests out many forms of movement at a dizzyingly rate. Phases where the six dancers seem to be in concert with each other are suddenly cut off as solitary routines unspool according to a hidden rhythm. The montage of movement is intoxicating: there are limbs as sinuous as spilt ink, spells of punch-drunk stumbling and Cubist panic. So many falls are smoothly escaped it seems the dancers are knowingly skittering on the brink of slapstick comedy. This mesmeric set of convulsions looks perplexing but it’s also obliquely educational: its splintered weave of stray manoeuvres, spiky irruptions and feinting grace captures the versatility of the body, like a choreographer’s manual come to life.

Trio A (1966) sees the troupe woozily shaking their limbs, twisting on the spot, making hieroglyphic moves with their arms, then lurching forward, pausing (the half-asleep moments in between steps are significant) and falling back again. The dancers are purposefully out of step, keeping to their own disconnected solos. Upstairs, the half-hour extract from Rainer’s first film, Lives of Performers (1972), is more readily grasped and perhaps open to mocking as a lugubrious example of certain formal tendencies in the experimental cinema of the 1970s – dream-theory interludes, hoary alienation effects and all. Still, there are some wondrously eerie tableaux in which pairs of lovers appear frozen, and a lone figure’s solo in which she seems to dance with her own shadow. All the films are so luminously grey they might have been shot on the moon. The sculptural entanglements of these sleepwalking bodies betray a chronic infatuation with Robert Bresson’s films, which had settled into their role as hallowed touchstones for cinephiles in the preceding decade. The longer you look at Rainer’s work, the more Bresson seems like a spectral presence stalking through it, sanctioning the wintry asceticism, the insistence on expressionless faces and the meticulous choreography of commonplace movements. A few dictums from his book Notes on Cinematography (1975) would readily apply to much of Rainer’s work: ‘not artful but agile’; ‘on the watch for the most imperceptible, the most inward movements’; ‘a single mystery of persons and objects’. This makes the ecstatic outburst of Ike and Tina Turner’s ‘River Deep, Mountain High’ during Chair Pillow (1969) an unexpected joy. All the dancers move in unison, clutching and throwing pillows, twisting and striking chairs, but there’s some private oddity exuding from it, too. As the chorus repeats and the actions loop the dancers start to look like mannequins in a lunatic piece of puppetry.

There remains the essential conundrum of what dancing that has wholly jettisoned narrative might mean, especially the sort schooled in Minimalism’s cool defiance of the comprehensible. But any hunt for clues would be forlorn. Lying next to Rainer’s book is my copy of Fred Astaire’s modest autobiography Steps In Time (1959) in which he professes his bemusement at the thought that his footwork might be unravelled in pursuit of a certain meaning: ‘I have no desire to prove anything by it [...] I just dance.’ And just to dance is demanding and mysterious enough.