10th Berlin Biennale: ‘This is a Space of Generative Violence, There Are No Utopias Here’

For our second report from BB10, ahead of its public opening tomorrow, a focus on KW Institute for Contemporary Art

For our second report from BB10, ahead of its public opening tomorrow, a focus on KW Institute for Contemporary Art

What is it about construction sites that fill errant children with such wonder? Fallen bricks, abandoned drums, teetering columns, filth. Amidst the scrapped and shattered, pockets of possibility unfold, granting willing adventurers entry to worlds that are otherwise, to worlds that are adjacent but not akin to reality. From the mess of it all, towers rise. Towers of junk but towers all the same.

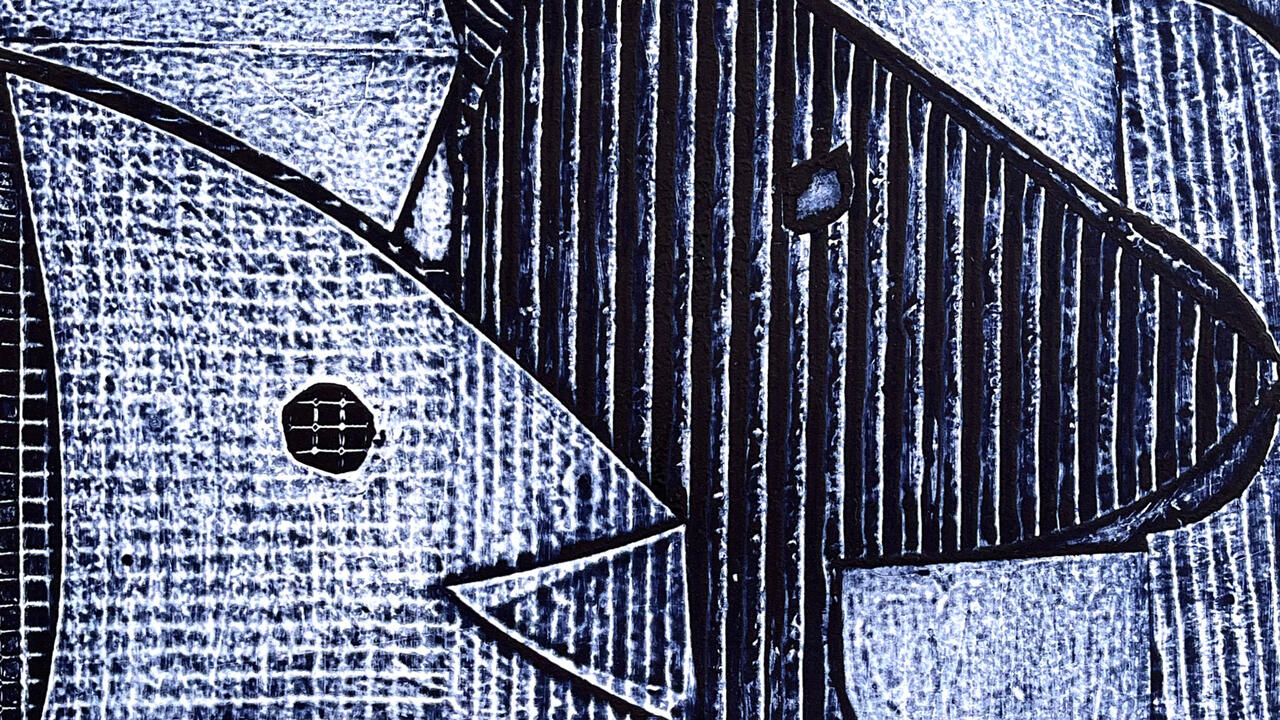

The central room of KW Institute for Contemporary Art is strewn with such debris: piles of orange bricks and upended pillars; polyethylene sheets and a vast orb of cardboard, suspended from the ceiling like a salvaged sun. Set within a warm orange glow, buckets and containers punctuate the space, each tactically positioned to catch drops of water that fall from above. The installation, Dineo Seshee Bopape’s Untitled (Of Occult Instability) [Feelings] (2016–18), which folds an arrhythmic drum-track, a video of a 1976 Nina Simone performance and individual works by artists Jabu Arnell, Robert Rhee and Lachell Workman, speaks not only to the desires of our abovementioned adolescents, those who tempt life out of the lifeless, but also to a central conceit of this year’s Berlin Biennale, curated by Gabi Ngcobo, with the curatorial team of Nomaduma Rosa Masilela, Serubiri Moses, Thiago de Paula Souza and Yvette Mutumba.

Under the title of Tina Turner’s 1985 song ‘We Don’t Need Another Hero’, the tenth iteration of the biennale rejects the notion that the lofty promises of prophets and saviours will ever liberate society from its historically-forged fetters. By way of a substitute, it champions a defiant act of self-preservation that might one day allow us to operate beyond the suffocations of established knowledge systems and power structures. As is visualized by Seshee Bopape’s (de)construction site, this is a space in which to break, bruise and batter that which we ‘know’, and see what, if anything, might be salvaged from the wreckage. This is, it seems, a space of generative violence. There are no utopias here.

Rarely is this violence as visceral as in Julia Phillips’s ‘Expanded’ (2016) series, for which the artist doused haggard sheer fabric in ink and stretched it across sheets of paper, only to remove the material once more and leave behind little but the memory of its presence. That memory is one of pain, as is so often the case. It is one that is ruptured and strained, punctured and pulled apart at the seams, and it invites into the room an image of a body, a skin, that is forever warring with (forever conditioned to war with) itself. Alongside these ghostly forms is a medical trolley strewn with savage, faux-medieval operating tools – the source of the suffering, perhaps. Its title reads: Operator I (with Blinder, Muter, Penetrator, Aborter) (2017).

If Phillips looks to expose the turmoil that is inherent to the body and, by association, the self, Joanna Piotrowska visualizes the anxieties that perforate familial structures. Piotrowska’s photographs are riddled with unease, her figures (invariably monochrome; invariably placed in contact with other bodies) forever hesitant as to their definition as subject or object. A looped 16mm film (Untitled, 2016) depicts a woman, bare-foot, adopting numerous self-defence stances against a black background, while a first silver gelatin print (Untitled, 2014) depicts hands clasping a limp forearm and a second sees a hand stretched over a woman’s face. There is a delicate simplicity to these visual gestures, but it is a simplicity that plays host to quarrelling notions of care, self-preservation, brutality and enduring struggle. It is a simplicity that makes lucid the volatile power structures that are native to each and every human relationship.

If, as Audre Lorde noted, self-preservation is an ‘act of political warfare’, then so too is the psychology of empathy in response to institutional (therefore: state-sanctioned) brutality. Simone Leigh’s film Untitled (M*A*S*H) (2018), which tells the story of a fictional order of black nurses who operated on the frontline during the Korean War, is the first of two included films that speak to the necessity and generative potential of such a compassion. The second is Luke Willis Thompson’s autoportrait (2017), which won plaudits when it premiered at Chisenhale Gallery, London, last year, but has faced biting criticism in the wake of the Auckland-born artist’s nomination for the Turner Prize.

The work is a silent portrait of Diamond Reynolds, who on 6 July 2016 broadcast to Facebook Live the ruthless murder of her partner Philando Castile, a 32-year-old black American, at the hands of officer Jeronimo Yanez. (On 16 June 2017, Yanez was acquitted of all charges.) While some see Willis Thompson’s gesture as a transformative elegy, one that allows its subject the opportunity to reclaim her own image, critics allege that the work aestheticizes – therefore, spectacularizes – black trauma, which is irrefutable. They allege that Reynolds’s willing collaboration in the project does not excuse this curation of (institutional and physical) violence, and that while Thompson does not identify as white (his heritage is mixed European and Fijian), he is white-passing, and therefore has no right to treat blackness as subject matter. On the latter point, we should watch our step, as while the mainstream art world is undoubtedly choked by a white fist, the imposition of rigid codes and regulations pertaining to fair use and appropriation would risk stifling those who they are drawn up to protect. However, when deliberating where to stand in relation to autoportrait, one might keep in mind an open letter written by Hannah Black in response to Dana Schutz’s 2016 painting Open Casket, a white artist’s depiction of Emmett Till: ‘non-Black artists who sincerely wish to highlight the shameful nature of white violence should first of all stop treating Black pain as raw material.’

From its titular definitive to its prioritization of artists excluded from the Western canon, the tenth Berlin Biennale makes an appeal to realism. It swears off the empty promises of false prophets and instead challenges its elected ‘we’ to take stock of, and subsequently control of, their own context. But in its attempt to reify this context faithfully, visualizing how oppressive systems of knowledge and power have left it dented, disorderly and all but devoid of clarity, it, too, sacrifices cohesion. In its meritocratic tempering of curatorially-imposed narratives and in its staunch refusal to ‘provide a coherent reading of histories or the present of any kind’, it opens the figurative door to moments of listlessness, others of sheer confusion. Whether or not this disjoint is by design – this is not an attempt to clean the mess, after all, but to make the mess visible to all – the presence of ‘We Don’t Need Another Hero’ at KW provides a welcome reminder that there will always be more stories to tell. We don’t need another hero, we just need those stories to be heard. However forged in pain, however full of promise.

- Read Pablo Larios’s report from BB10, asking: We Might Not Need Another Hero, But Do We Need Another Fair-to-Middling Biennial?

The 10th Berlin Biennale runs from 9 June – 9 September, 2018, across various venues.

Main image: Dineo Sheshee Bopape, Untitled (Of Occult Instability) [Feelings], 2016–18, bricks, light, sounds, videos, water, framed napkin, installation view (detail), 10th Berlin Biennale, KW Institute for Contemporary Art, Berlin, Including works by: Jabu Arnell, Discoball X, 2018, Lachell Workman, Justice for___, 2014, Robert Rhee, EEEERRRRGGHHHH and ZOUNDS (both from the series ‘Occupations of Uninhabited Space’, 2013–ongoing), 2015. Courtesy: Dineo Seshee Bopape, Jabu Arnell, Lachell Workman, Mo Laudi, Robert Rhee; photograph: Timo Ohler