9th Berlin Biennale for Contemporary Art

Various locations, Berlin, Germany

Various locations, Berlin, Germany

The 9th Berlin Biennale is easy to dismiss – for being too unpolitical, too hip and homogenous, too jaded, too complicit with capitalism, too slick. But it’s just as easy to like this event, curated by the New York-based collective DIS: it is radically contemporary and, on account of the complexity and intractability of this contemporary reality, it refuses to position itself explicitly. The 9th Berlin Biennale eschewed a grandiloquent criticality whose credibility would inevitably be nullified by its own privileged status and implication. This complex nexus of superficial optimism, digital-native chimera, body optimization, health and performance rituals, post-gender and post-humanism debates, tech obsession, problematization of capitalism and rhetoric of acceleration can thus be either approved of or disparaged – for, essentially, the same reasons.

However slick and thus impenetrable it may appear, the success of this Biennale ultimately hinges on its concept of ‘the present’. With its subtitle, ‘The Present in Drag’, the contemporary is grasped as fundamentally paradoxical and contradictory. And, by implication, the more paradoxical something is, the more contemporary it is too. ‘Paradessence’ is the portmanteau concept proposed by the Biennale for the constitutive simultaneity of this and that, here and there. Logically enough, this makes it impossible to adopt a position in the conventional sense. Because one is always at least two – and often more.

What the Biennale does not do (which makes it so fresh and new compared to its predecessors) is play with the simultaneity of the non-simultaneous, digging into the city’s past, contrasting a ‘former East’ with a ‘former West’. Previous Biennales have often done this, taking place along the route of the Berlin Wall (5th edition, 2008), in the multicultural former squatters district of Kreuzberg (6th edition, 2010), or in the tranquil district of Dahlem in the depths of the former West Berlin (8th edition, 2014). The 9th Biennale works differently. Instead of going into historical depth, bringing incompatible elements together on a timeline, for this year’s Biennale, DIS present everything side-by-side in a restricted space. It works laterally, like the Internet. Everything’s available. Just a few clicks away.

With their choice of venues – the Academy of Arts on Pariser Platz, a sight-seeing boat on the river Spree, the private European School of Management and Technology (ESMT) on Schlossplatz in Mitte, and the newly opened Feuerle Collection in Kreuzberg – DIS proved genuine skill. Each makes a precise conceptual statement: while the boat clearly says tourism and the Feuerle Collection’s private museum stands for the merging of institutions and private collecting (this is the first time that part of the Berlin Biennale has taken place at a private venue), the Academy of Arts and the elite business school showcase an impressive diversity and complexity.

At ESMT, one enters the former East German State Council Building that now houses the business school through a former gateway of the old Hohenzollern Palace. (This houses the balcony from which Karl Liebknecht declared a socialist republic in 1918 and which, after the Palace’s bomb-damaged remains were demolished, was integrated into the new East German building in memory of this historical moment). But this piece of history is immediately over-written by a busy present: walking through the huge lobby, one passes flatscreen monitors flashing current stock-market prices (part of the school’s own interior design) as well as a PR gimmick belonging to Berlin’s insipid city marketing campaign ‘be Berlin’ (including a sleazy testimonial) before walking up the stairs past Walter Womacka’s monstrous stained glass Scenes from the History of the German Worker’s Movement (1964) in the style of Socialist Realism. On the first floor, one then looks back through the huge windows at Schlossplatz, where the first sections of fake-classical façade are currently being installed on the concrete bunker reconstruction of the ‘old’ Hohenzollern Palace: wonderful layering, multiple overwritings with different ideologies, with present, past and future.

The works on show here have trouble competing with the location – standing out are neither Simon Denny’s excursion into the world of the blockchain technology on which the post-national digital economy of Bitcoins is based (Blockchain Visionaries, 2016); nor GCC’s large-scale installation Positive Pathways (2016) allegedly about positive thinking and self-optimization; and certainly not Katja Novitskova’s cut-out figures with flame motifs and mighty animal horns that stand around forlornly in front of windows and between the stock exchange screens on the ground floor (e.g. Expansion Curves (fire worship, purple horns), 2016). The site itself is too powerful; the stories it tells are enough. DIS, who often stated that they saw themselves primarily as tourists in Berlin, chose their venues with the precision of geo-targeting and big data: ‘Siri, show me all the places in Berlin where global capitalism is at home, where the East German past still makes its presence felt, and where a prestigious, ideologically charged construction project is underway.’ This is unbeatably efficient – with the result that what is then presented as content (i.e. art) at these locations is almost beside the point.

The same applies to this biennale as a whole. One often has the impression that the individual works are interchangeable, as if they were just personal expressions of a larger-scale programme. Particularly at Kunst-Werke, the home venue of the Biennale since its inception, one is struck by the strangely diffuse quality of many works, by the degree to which they overlap, sometimes having little to say in their own right. This patchwork that only functions as an overall whole – as an analysis of the present, as a generational statement (in places, the biennale ironically reflects this characterization of ‘digital natives’ back as a projection, but without ever distancing itself from it).

Many of the works here are highly ‘emotive’, with pathos-laden soundtracks, like Cécile B. Evans’s installation-cum-video What the Heart Wants (2016), in which a sad story of loneliness, love and memory in a post-humanist age is told via images of solitary disembodied beings in designer apartments, dancing avatars at server farms, and people falling from the sky. Or Wu Tsang’s martial arts and kung-fu inspired short film Duilian (2016) that blends the historical figure of Qiu Jin, a Chinese revolutionary and sword-fighter, with a queer inflection on the relationship between fighting and dance. In among these works: a sponsored deluxe unisex bathroom installation by Shawn Maximo; Juan Sebastián Peláez’s Instagram-friendly cut-out Rihanna, whose head has slipped into her décolleté (Eweipanoma (Rihanna), 2016); an avalanche of printed-out unanswered emails by Camille Henrot (Office of Unreplied Emails, 2016); or Amalia Ulman’s dreamy look at her own Gucci and Prada loafers which, according to an accompanying text, is the online performance of a faked pregnancy, addressing gender roles and relationships of dependency (PRIVILEGE, 2016). Toilet humour purged of all grossness, clickbait-optimized Photoshop gimmicks, helpless submersion in the communications flood, and flights into the superficiality of invented social-media characters: much of the material at KW exudes a strange feeling of isolation, failed communication and detachment from any specific social context. And at the same time a longing makes itself felt, a timid, suppressed cry for community, but one which then (or so the aesthetic suggests) finds commercial exploitation as the only possible form of collectiveness: looked for a friend, found a business partner.

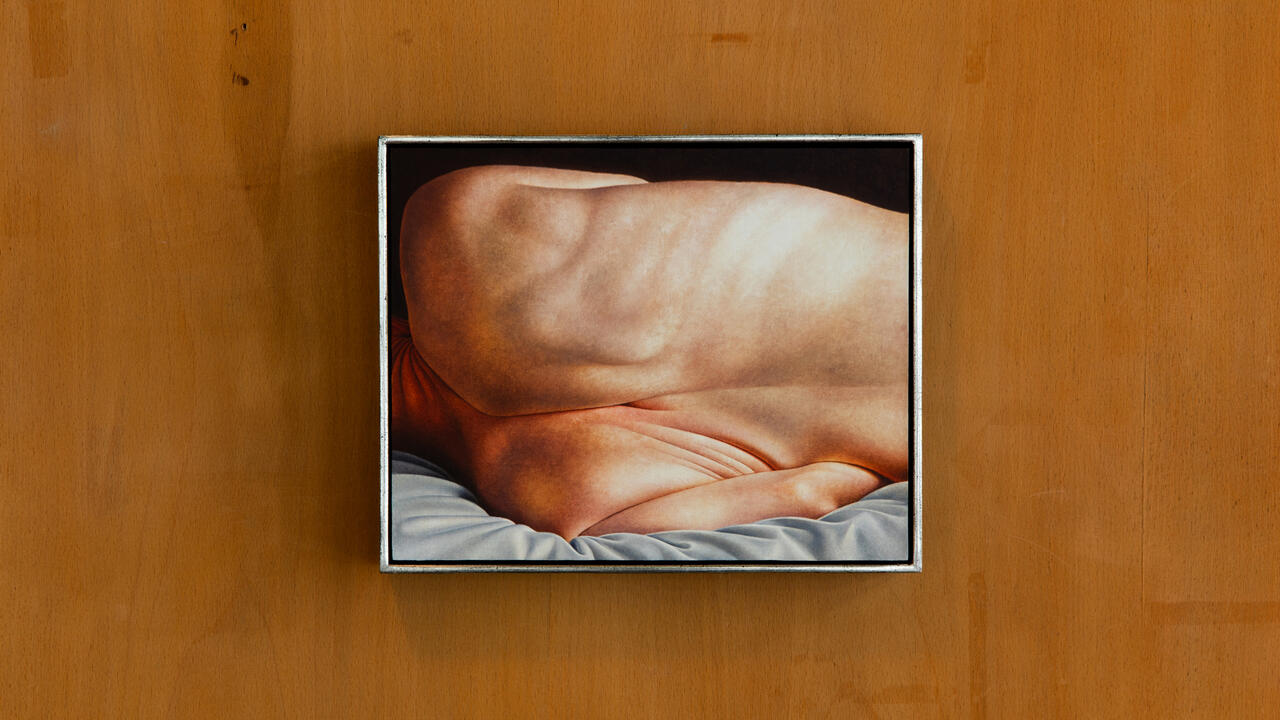

The main force of the 9th Berlin Biennale, however, is concentrated at the Academy of Arts on Pariser Platz – a location with a power similar to that of the State Council Building, also with a view, this time of Berlin’s biggest tourist magnet, the Brandenburg Gate. Its immediate neighbours include the American and French embassies, as well as the European headquarters of the American arms company Lockheed Martin. There are several good pieces here, including Simon Fujiwara’s funny The Happy Museum (2016) for which he worked with his brother Daniel, an expert in the quantification and monetization of ‘happiness’ in business, resulting in an installation with found items in and on plinths and vitrines (most with links to Germany): a hi-tech children’s seat for cars, a garden gnome, a new age flyer advertising ‘inner organ massage’. Apart from this, here, as at the other venues, the show was thronged with work by artists from the extended DIS milieu. Not so long ago, this kind of work was being referred to as Post-Internet. Timur Si-Qin’s contribution is a model landscape that takes photographs of itself (A Reflected Landscape, 2016), Anna Uddenberg marshals an armada of grotesque female figures, some of them in obscene poses, posed on suitcases and the like (e.g. Cutesy Counts and Lady Unique, both 2015), while Ryan Trecartin and Lizzie Fitch are represented by one of their perfectly produced environment-meets-hysteria video installations (including the video Mark Trade, 2016). It is at this site – previously used as a location for the American spy series Homeland – that Max Pitegoff and Calla Henkel installed photographs taken within a villa used as a home for American diplomats in Dahlem (Untitled, (interiors), 2016). Jon Rafman uses an Oculus Rift headset to send visitors on a dystopian trip from the Academy’s upper balcony, in the course of which Pariser Platz seems at first to be flying into the air before falling into a gloomy underwater world where huge beasts devour one another (View of Pariser Platz, 2016). A more concrete impression is made by Christopher Kulendran Thomas who, in a slick interior, presents an advertising campaign for his company New Eelam (2016), combining the history of the Tamil liberation struggle in Sri Lanka with a proposal for a worldwide post-capitalist accommodation platform: Airbnb meets revolutionary rhetoric. Hmm ...

The exact opposite of this piece is Halil Altındere’s video Homeland (2016), a music video shot with Mohammad Abu Hajar, a rapper who fled from Syria to Berlin. This work is strikingly different, throwing the problem with many of the other exhibits into stark relief. Initially, the video adopts the emphasis on a slick surface generally associated with DIS and its artistic milieu. We see a number of slim, healthy people doing yoga on a landing stage. The water shows the reflection of the camera drone making the film. Then refugees step onto the beach, make life preservers out of old plastic bottles, run for their life through catacombs, Abu Hajar flies over a border fence in a bizarre backwards somersault and, on the other side, begins rapping in grim tones, over synthetic beats by club duo Nguzunguzu, about his experiences while fleeing and as a refugee in Berlin. The film is presented in such a way that Pariser Platz is visible behind the huge hanging flat screen. Apart from its thematic real presence in Berlin, the video is characterized above all by one thing: a straightforwardly political position. Whereas almost all of the other works in the Biennale content themselves with showing the absurd coexistence of media representation and so-called reality, of politics and health mania, of isolation in times of digital dating and collaborations in a sealed inner world, without any further comment, in Altındere’s work something breaks through the seemingly impenetrable bubble of algorithmic filters: hard political reality, reflected in the way someone shows old-school anger and vehemence, attacking something instead of just showing it. Politics here is another word for a clear position. The difference consists in the way things are looked at, not just in sheer fact that they are addressed.

In the face of everything that has happened in the world since DIS were appointed as curators of this biennale two years ago – war in Syria, refugee crisis, terrorist attacks, right-wing populism, Brexit, putsch in Turkey, Trump – it feels now that it’s simply not enough to highlight such paradoxes and flee into a ‘post-critical’ gesture. Any hope that DIS might give the Berlin Biennale an injection of new life and update it to the present (which, to an extent, they have) is ultimately shattered by the fact that the present has long since taken on a totally different appearance. Without denying the complexities, it would have been time to adopt a clear political position. It would be going too far to blame DIS for the fact, but: however ‘contemporary’ this Biennale may be, it also reveals that the present has since moved faster that any picture one might be able to make of it.

Translated by Nicholas Grindell