Agnes Denes

Ludwig Museum, Budapest, Hungary

Ludwig Museum, Budapest, Hungary

Agnes Denes’ best-known work, Wheatfield – A Confrontation, was planted in summer 1982 in a landfill on the southern tip of Manhattan below Wall Street (now Battery Park). Photographic documentation of Wheatfield… often appears in survey books of the American Land art movement, yet the image of the piece can seem like a non sequitur without seeing Denes’ other works alongside it. Readers are left guessing what the artist must have done to arrive at Wheatfield…, and what else she has accomplished since then.

A major survey exhibition mounted by the Ludwig Museum in Budapest demonstrated the extent of Denes’ labours. Commissioned by the late Katalin Néray (and seen through by Ludwig curator Róna Kopeczky) the exhibition also celebrated Denes as a Hungarian expatriate, intimating that her connection with the land might evolve from her Magyar roots. This association also personified and feminized her work, suggesting that her practice evolves from an emotional attachment to the land and embodies a sense of care associated with late-feminist theory.

Land art and earthworks are akin to landscape architecture and ‘greening’ projects inasmuch as they require significant research, lengthy gestation periods and long-term commitments from clients. Projects are often borne of competitions, meaning that many of them never move beyond the proposal stage, which explains the status of Denes’ work. The exhibition was stacked with proposals – architectural drawings, sketches and schematics – for projects that haven’t been realized, yet represent months or years of input from the artist. As if acknowledging this temporal deferral that riddles her work, Denes has developed a strand of her practice based on time capsules – a popular memorial technique. Time Capsule Art Park, Lewiston, New York (1979), for instance, is to be opened in 1,000 years and contains the microfiche of a questionnaire about the current state of and future predictions for humanity. For Denes, the burial of the capsule represents mankind’s common fate and its relation to the eco-cycle.

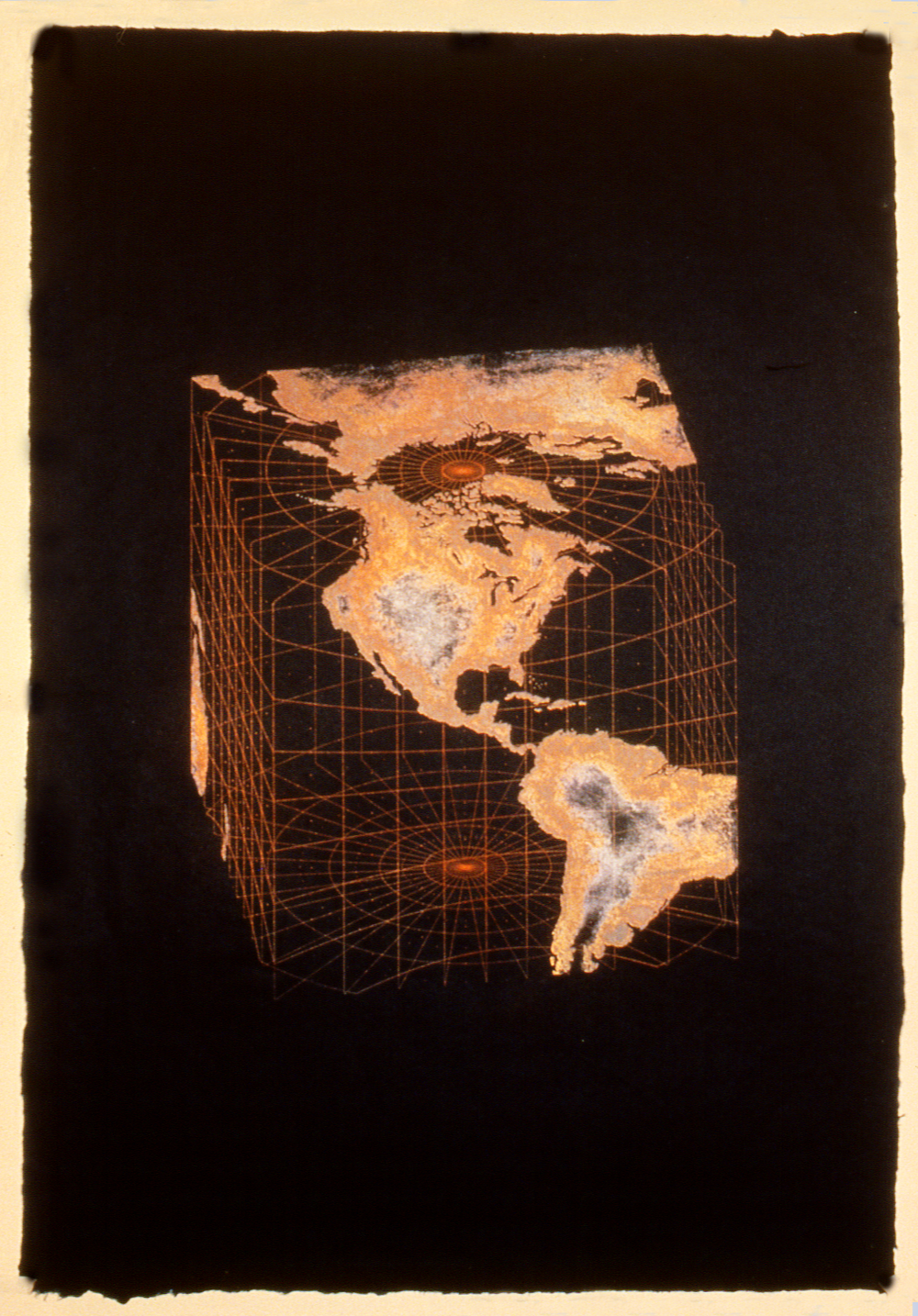

Denes’ ‘Antarctic Time Capsules’ (1980–6) rely on an equally active but sustaining eco-cycle: that of deep freezing, coupled with glacial movement. The artist planted capsules packed with a range of biological and technological samples into fissures at the summits of Antarctica’s four major glaciers, predicting that they could be ejected into the sea in some 50,000 years and wash up in Africa, South America and Australia. Again, the audience can only experience this work as documentation in the form of drawings, maps and texts. Tree Mountain – A Living Time Capsule (1992–6), on the other hand, utilized the participation of 11,000 people to plant 11,000 silver fir trees (hence the five years it took to enact the work). Planted on the site of a gravel mine in Ylöjärvi, Finland, as an environmental reclamation project, the trees are arranged in a mathematical sequence of elliptical radii from the summit of a 420-metre-high hillock, which will become apparent to the naked eye as the trees mature over the next 400 years.

Denes’ renderings of the geometrical patterns the trees will make are beautiful – full of the swirls and whorls scientists have found in the compositions of cells and atoms. There are about 20 such drawings in the show – mainly plans for pyramids (The Pyramids, 1969–ongoing) made by hand with pencil and India, gold and silver ink on vellum. The drawings are geometrical representations of mathematical theories, rather than plans for built structures. Each one has thousands of delicate marks created by hand with the precision of a computer, making one marvel at Denes’ dexterity and wonder (again) at her patience. Denes is principally fascinated with morphing the pyramid shape into avian forms that look like a heron in flight (Bird Pyramid, 1984), which suggests that gravity is the other force, after time, that she wants to overcome. In this light, Denes’ projects seem to connect to the lineage of Leonardo da Vinci’s plans for flying machines and Frank O. Gehry’s pioneering use of Dassault aircraft design software, rather than to the traditions of monumental Land artists.