Alexander Tovborg’s Spiritual Yearning

At Kunsthal Charlottenborg, the artist’s ecclesiastical paintings channel the ethereal visions of William Blake and the earthy primitivism of Paul Gauguin

At Kunsthal Charlottenborg, the artist’s ecclesiastical paintings channel the ethereal visions of William Blake and the earthy primitivism of Paul Gauguin

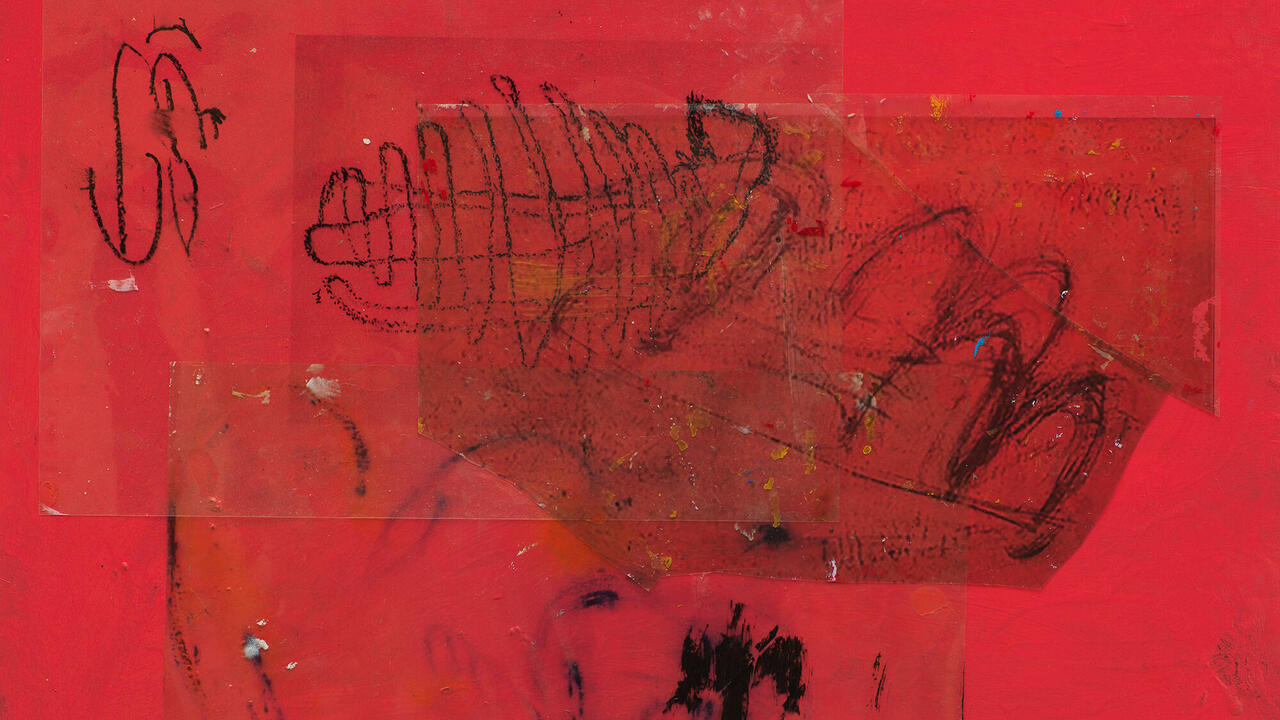

A central nave flanked by a series of aisles and transepts, the layout of the Kunsthal Charlottenborg bears a close resemblance to that of a cathedral. It’s fitting, then, that Alexander Tovborg has reimagined it as a place of worship in ‘The Church’, his largest solo exhibition to date, and his most searching exploration yet of spiritual yearning – and personal gnosis – in our increasingly secular age. Long blocked-up with plasterboard, the institution’s ten vaulted windows have been exposed by the Danish artist, who’s overlaid their panes with collaged images of flowers and fruits cut from sheets of translucent, jewel-toned acetate, which recall the simplified forms and reverent joy in nature’s fecundity that characterize Henri Matisse’s stained-glass windows in the Chapelle du Rosaire in Vence. As the Earth makes its daily journey around the sun, these images are projected onto the floor like visions sent from heaven, their shapes shifting by the hour, until night falls and they finally fade out.

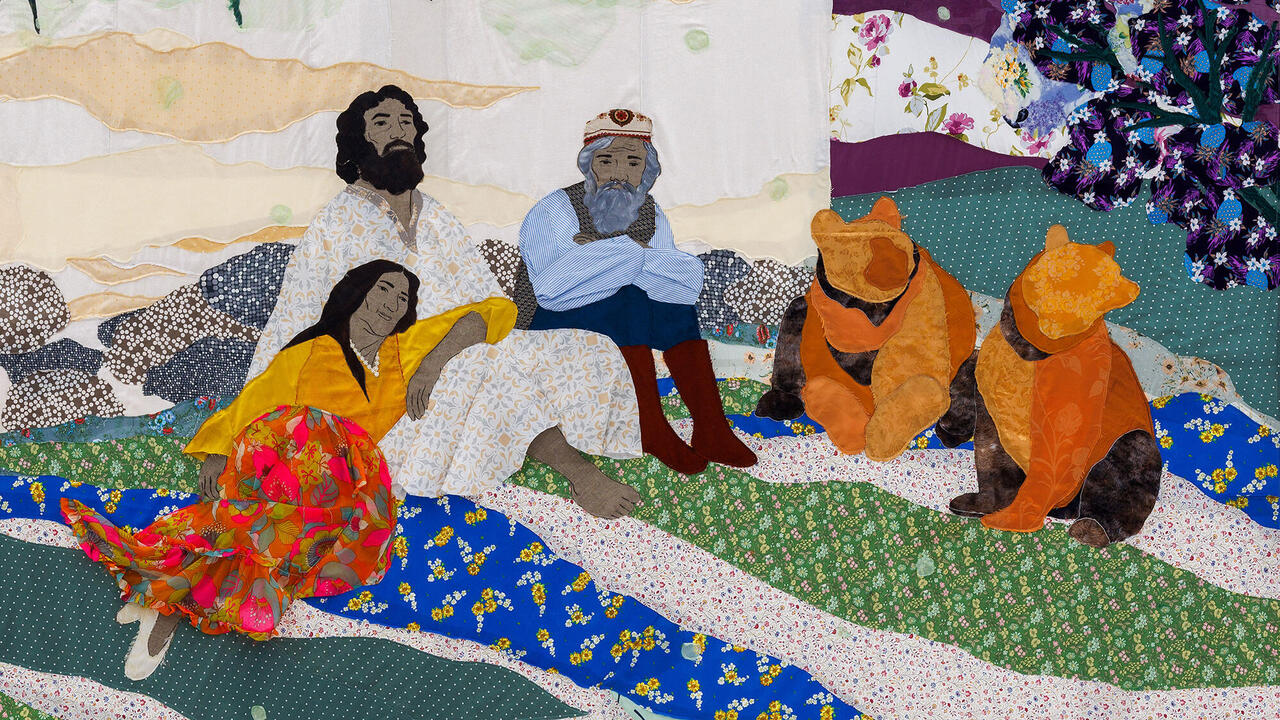

Conceived as a single installation, ‘The Church’ presents its constituent works as though they were ecclesiastical furnishings and decor. Accordingly, a ceramic font shaped like a Madonna and child, Døbefont (Dea Madonna Baptismal Font, 2023), is installed near the show’s entrance, while in a ‘lady chapel’ at its far end hangs Beatrice (2023), an extraordinary, cinema screen-sized painting that channels both the ethereal visions of William Blake and the earthy primitivism of Paul Gauguin. Its subject is a scene from Dante’s The Divine Comedy (c. 1308–21), in which the spirit of the poet’s deceased muse suddenly appears as he approaches paradise, demanding: ‘What right had you to venture […] here?’ We might equally ask this question of Tovborg, who doesn’t identify as Christian, but nevertheless places Christianity’s sacred narratives and iconography at the centre of his practice. I suspect he’d respond that these things represent human attempts to know the unknowable divine and are thus by definition flawed. Why not, then, pry open their mythopoeic cracks?

In place of an altar hangs Eve (2022–23), a trio of near-identical canvases portraying the titular biblical character. While she has adult facial features, there’s a foetal bulge to her forehead, and the benign-looking serpent nestling against her body suggests an umbilical cord. Having consumed the forbidden apples of the tree of knowledge, she’s about to be reborn as the first true human, burdened and blessed with moral sense. Maybe this was her plan all along. Better to be cast out of Eden than to spend eternity as the infantilized pet of some patriarchal deity. The Book of Genesis is revisited in a smaller painting, Edam (2022–23), where Eve and Adam are recast as a composite intersex being (a logical move, given scriptural accounts of how she was fashioned from his rib), who resembles a serene, blue-skinned sprite. The work is essayed on wood sawn from a church pew, in acrylics laced with holy water. I get to thinking about how art objects become imbued with an aura of the numinous. Had Tovborg used an unsanctified liquid to thin Edam’s pigment, would this enigmatic, ravishingly beautiful vision of humanity’s beginnings feel any less charged?

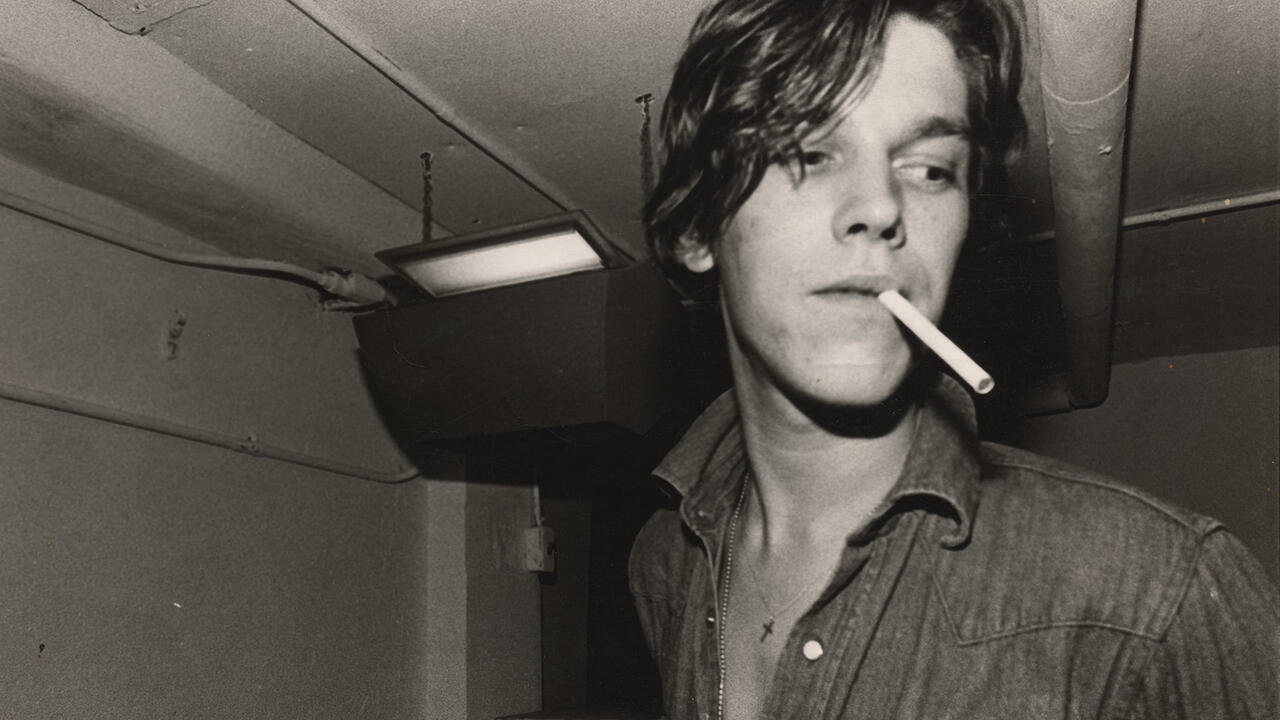

Suspended from the ceiling, the rainbow-hued Teenage Jesus (2022) is a painting of a crucified adolescent Messiah and a reminder that the gospels say nothing of Christ’s life between the ages of 12 and 30. The work suggests he experienced his first, unrecorded Passion and resurrection during puberty. If so, what are the theological implications? As a chronic agnostic, I’m not sure. What I’m more confident of is the sincerity and deep spiritual pull of ‘The Church’. Philip Larkin’s poem Aubade (1977) described Christian tradition as a ‘vast, moth-eaten, musical brocade’. Tovborg holds it up to the light and makes it glow.

Alexander Tovborg’s ‘The Church’ is on view at Kunsthal Charlottenborg until 6 August.

Main image: Alexander Tovborg, The Apple II, 2023, installation view. Courtesy: the artist; photograph: David Stjernholm