Around Town: Basel

Three new exhibitions from Lena Henke, Yngve Holen, and Anne Imhof

Three new exhibitions from Lena Henke, Yngve Holen, and Anne Imhof

For its conspicuous summer season, Kunsthalle Basel hosted two variations on a theme of barely swallowed rage. On the ground floor, Yngve Holen’s ‘VERTICALSEAT’ spoke an austere, minimalist language, wrought from cage fences, blown-glass ovals in the shapes of Boeing Dreamliner airplane windows, and a Porsche Panamera coolly sliced into quarters (CAKE, 2016). Excised from their usual domains, these objects are reduced to an array of violent, inequality-creating machines paired with the glaring eyes of surveillance systems and top-down control. Holen’s was a fast-paced and inhospitable show: I was virtually pushed out of the space by the aggression of the work, and by the hot light emanating from a pair of bus headlamps, Hater Headlight (2016), which burned angrily on my retinas for several minutes afterward.

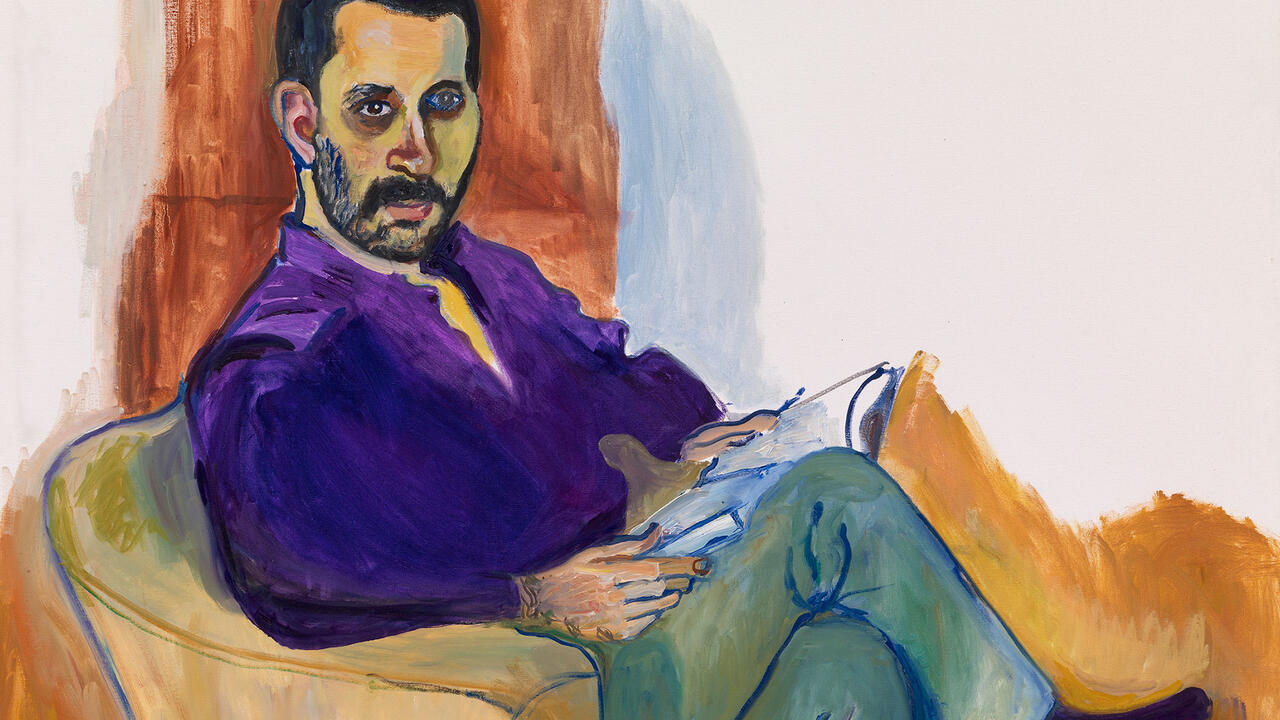

Upstairs, Anne Imhof’s ‘Angst’ expressed an interminably slow rage: diffuse, suggestive and hard to shake off. The baroque, operatic structure of the exhibition featured a small cast of actors (and, occasionally, falcons) performing a series of scenes – ‘The Lover’, ‘The Clown’, ‘The Spitter’ – over a number of days. The macho sculptural scenography included punching bags; a dirty, ‘Angst’-branded hot tub; wall rails, towels and gym bars; complemented by spectral, barely finished paintings by Imhof depicting the cast making signature gestures. The focus on the paintings in the exhibition text seemed a little overstated, perhaps to prevent those who visited outside performance times from feeling like they had missed the event.

When I attended the performance of ‘The Spitter’, the default iPhone alarm tone echoed around the space regularly, sending confused audience members to check their coats and bags, like so many Pavlovian dogs. In fact, the sound was used as a means of indicating that the actors should move – glacially, as though through glue – to arrange themselves into defiant tableaux: leaning, crouching, posing, looking away. The punching bags were routinely shoved and transformed into pendulums. Falcons appeared as ‘prophets’. Actors ingested olive pips and Pepsi, then spat them out rhythmically, or applied cream to their stomachs and palms and shaved them. Time burned away on cigarettes disaffectedly smoked, shared and extinguished in the hot-tub water.

If these skinny, bored bodies in casual streetwear seemed like a collection of models at a photo shoot, then the cannibalization of fashion in ‘Angst’ appears as an act of deliberate autophagy. One of the lead actors in Imhof’s piece is a prominent model for Balenciaga and Vêtements – labels currently commanding attention for garments that speak a kind of capitalist-realist language. Adolescent angst looks beautiful on the young and is good for selling a style, yet today’s youth is more disenfranchised than that of any generation for decades. As they sucked on and spat out Pepsi and pits, with their gangly, veiny, limp arms, Imhof’s actors appeared smacked out – as if their cheap pop were heroin. Yet, if these young people seemed to be selling their bodies for little return, it’s perhaps indicative of today’s atmosphere of publicity, in which we create images of ourselves that we can trade for an audience’s attention, as we march to the beat of the smartphone’s drum.

Elsewhere, at the bellwether off-space SALTS, an exhibition by Owen Piper and Lili Reynaud-Dewar described a long-term, collegial pair of practices, while a compellingly embodied poetry exhibition curated by Harry Burke emphasized language as image – including Arlene Schloss’s text works, in which ‘ai’ and ‘i’ sounds were replaced with scrawly drawings of eyes. In the garden outside, Lena Henke’s installation, ‘MY HISTORY OF FLOW’, (guest-curated by Anna Goetz) comprised a full-sized, cylindrical water tank placed on top of a squat, white cubic exhibition space, like an outhouse or grotto. With the tank connected to the nearby river Birs, and the entire structure angled a couple of degrees askew, water cascaded into the space from horizontal slits on one of the interior walls – an experience exacerbated on the opening day by a downpour, creating a flooded space that could only be traversed by stepping stones formed from logs and piles of unsold local newspapers.

Henke’s title carries connotations of menstruation, which female consumers see scaled with colours and symbols on the packaging of sanitary products, suggesting an unabashedly tell-all tone, as though the water pouring in from the walls and pooling on the floor might relate directly to the history of the artist’s own body, with all the varying degrees of delight and gloom that might suggest. The objects inside, however, articulated a more surreally imaginative engagement with architecture and infrastructure: the space was populated by ceramic lily pads, after famed garden architect Roberto Burle Marx, while a small wonky ceramic building, in the shape of Pier Francesco Orsini’s Leaning House (1552), was, in fact, the only upright object in the tilted structure. The obvious antecedent for Henke’s installation is Robert Gober’s watery masterpiece Untitled (1995–97), permanently displayed nearby at Basel’s Schaulager. The water running down the stairs of Gober’s installation into a rock pool under the floor dramatizes a sense of solemn tragedy that moved me to tears when I first saw it. As a kind of wobbly travesty, Henke’s installation was a scrappy catastrophe of a building and a miniature history of hysterical, playful, emotional architectures.