Art Brut in America & Unorthodox

American Folk Art Museum & The Jewish Museum, New York

American Folk Art Museum & The Jewish Museum, New York

‘Art Brut in America: The Incursion of Jean Dubuffet’ at the American Folk Art Museum concerns the decade from 1952 to ’62 when the French artist made a temporary loan of 1,200 works produced by his ‘confined comrades’ – mainly artists working in isolation in prison or psychiatric institutions – to fellow artist Alfonso A. Ossorio. Curator Valérie Rousseau opens the exhibition with five works by Ossorio, whose wild rendering and use of vibrant colour was deemed by Dubuffet to be tainted by culture and annexed from his art brut collection. Rousseau sectioned off Ossorio’s works using archival material and photographs, including a slideshow of the collection as Ossorio installed it in his Long Island mansion, where it stayed for ten years.

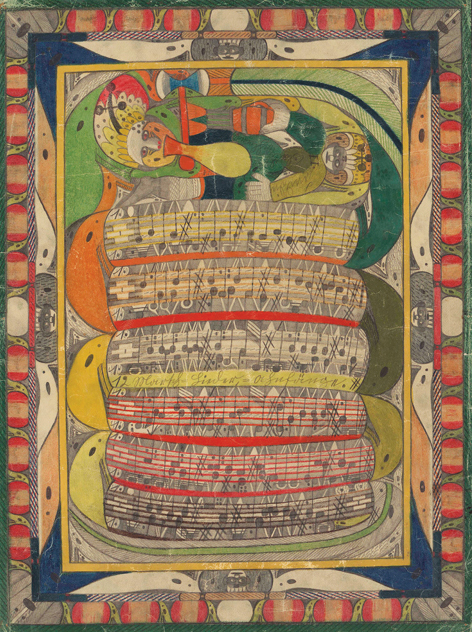

The collection began in 1945, inspired by Dubuffet’s encounter with the work of Adolf Wölfli, whose musical scores become blueprints for intricate, surreal drawings such as Untitled (Saint Adolf Bitten in the Leg by the Snake) (1921). Unlike Wölfli, who was confined to a psychiatric institution for most of his life, Jeanne Tripier only began producing works such as Croquis de fantaisie (Fantasy Sketch, 1937), which blends text and image using inventive materials such as hair dye and sugar, when she was in her 50s, following a relatively ordinary existence in Montmartre.

The disparity in their experiences underscores Dubuffet’s false dichotomy between what he called ‘art brut’ and ‘art culturel’ – or the idea that to tap into artistic emotions one’s subjectivity had to be untainted by culture. However, Dubuffet championed the work he included in his collection as capital-A Art rather than art by the mentally ill; he felt this earlier segregation was as arbitrary as separating out art produced by people with knee problems.

A concurrent exhibition at the Jewish Museum, ‘Unorthodox’, is indebted to Dubuffet’s ethos. It is as if Dubuffet planted a small seed in New York that sprouted half a century later into this show, organized by Jens Hoffmann, Daniel S. Palmer and Kelly Taxter, which can be read as a contemporary interpretation of the same, anti-normative project. Featuring 55 artists from different countries and time periods, ‘Unorthodox’ attests to important social and cultural shifts produced by, amongst others, the feminist and disability rights movements; it also aims to comment on the current state of ‘art culturel’. The curators’ wall text deliberately avoids defining terms such as ‘unorthodox’ or ‘normative’, aiming instead for an experiential argument about what these might mean.

The main gallery space is fitted with hallway-like, cramped walls that resemble art fair architecture. Every wall is packed, giving the impression that the works should be experienced in relation to one another rather than as individual pieces. Valeska Gert’s two performances for video set the tone at the entrance: Das Baby and Der Tod (Baby and Death, both 1969) present the artist’s unselfconscious, over-acted scenes of the first and last stages of human life.

The curators prefer what they refer to as ‘untapped artistic practices’ over ‘usual suspects’ who traffic through global surveys. Acknowledging that the exhibition is one such ‘normative’ context, the point is to gather artists usually excluded from these venues and see what happens when they are clustered together without the company of recognizable names. There were some exceptions. A work by emerging artist Park McArthur is installed in front of sculptures by Diane Simpson; both projects are rendered in a slick conceptual vocabulary that felt incongruous with their more intuitive-looking neighbours. David Rosenak, on the other hand, appears on the surface to be a photo-realistic landscape painter, yet emphasis shifts when we learn from the exhibition material that Rosenak in fact paints only about two works per year and the accuracy of his depiction reflects his battle with Parkinson’s. Today, it is common for an artist such as Rosenak, whose work doesn’t seem to aspire to participate in the global contemporary art conversation, to be included in a biennial-style exhibition alongside more recognizable names. However, it is through the absence of well-known art-world figures that ‘Unorthodox’ outlines an idea of normative, orthodox contemporary art.

‘Unorthodox’ is about undermining a specific idea of what art is and whom it is for. The show is a statement about contemporary museum practice, which is subject, too often, to vested interests, favouring artists with strong collector bases and tested critical reception. Said Dubuffet: ‘Research artistic productions by obscure people, with a special character of personal invention, spontaneity, freedom from conventions and accepted ideas.’ That quotation could just as well sum up the success of ‘Unorthodox’. Although ‘Art Brut in America’ excuses Dubuffet’s reliance on artists’ ‘pure’ subjectivity as source of their formal experimentation, the coincidence of the two exhibitions is evidence that Dubuffet’s project has life beyond its historical moment.