Atelier Van Lieshout’s Doomsday Devices Take Us Back to the Industrial Revolution

At Pioneer Works, Brooklyn, the Dutch artist’s dystopian grandeur forces us not just to think about the industrial condition, but actually feel it

At Pioneer Works, Brooklyn, the Dutch artist’s dystopian grandeur forces us not just to think about the industrial condition, but actually feel it

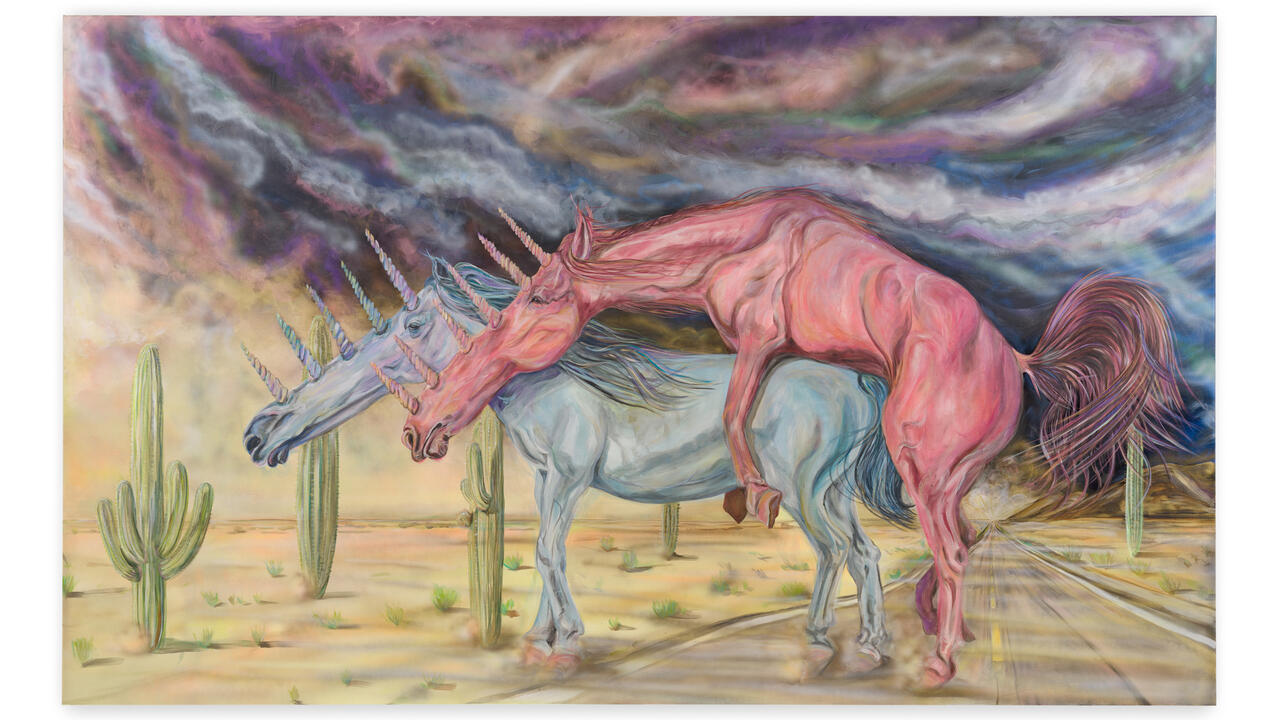

Joep Van Lieshout is a highly unreasonable artist. That, at any rate, was the verdict of the Louvre, which abruptly pulled one of his sculptures from a planned installation in the Jardin des Tuileries in 2017. It was easy to see why: the huge structure, entitled Domestikator, suggested an agricultural shed that had, Transformer-like, assumed the guise of a man anally penetrating an animal. Van Lieshout insisted the work was intended to probe ‘the ethics of technological innovation’ and was ‘not at all explicit’, but to no avail. When his sculpture was rejected, he fumed that museums these days are pathetically risk-averse, ‘directed by teams of lawyers and marketing people.’ He may have had a point.

Now Van Lieshout has crash-landed at Brooklyn’s Pioneer Works, surroundings much better suited to his particular brand of dystopian grandeur. His retrospective exhibition there confirms how awe-inspiringly unreasonable he can be. Towering in the centre of the gallery is the twelve-metre tall Blast Furnace (2013), a sculpture inspired by nineteenth-century steel technology. Fitted out with balconies, staircases, roughly made furniture and even a toilet, it is the centrepiece of his series ‘The New Tribal Labyrinth’, which imagines a cultic return to the days of the early industrial revolution. The work is eerily appropriate in the 1880s Pioneer Works building, formerly used to make infrastructure like railroad tracks and sugar refinery equipment, a proverbial ‘Satanic Mill.’

Blast Furnace could, in theory, be inhabited. As far as smelting goes, though, it is non-functional. Even if it could be lined with brick and fired up, it would need to be fed thousands of pounds of raw metal and coal per day, and connected to a vast distribution system on the other end. Though enormous by the standards of art, it is inadequate by the standards of industry. This is typical of Van Lieshout, who loves to undermine his own mad ambition with dark pathos. His fantastical machines are intended as social metaphors, with a strong Freudian undertow.

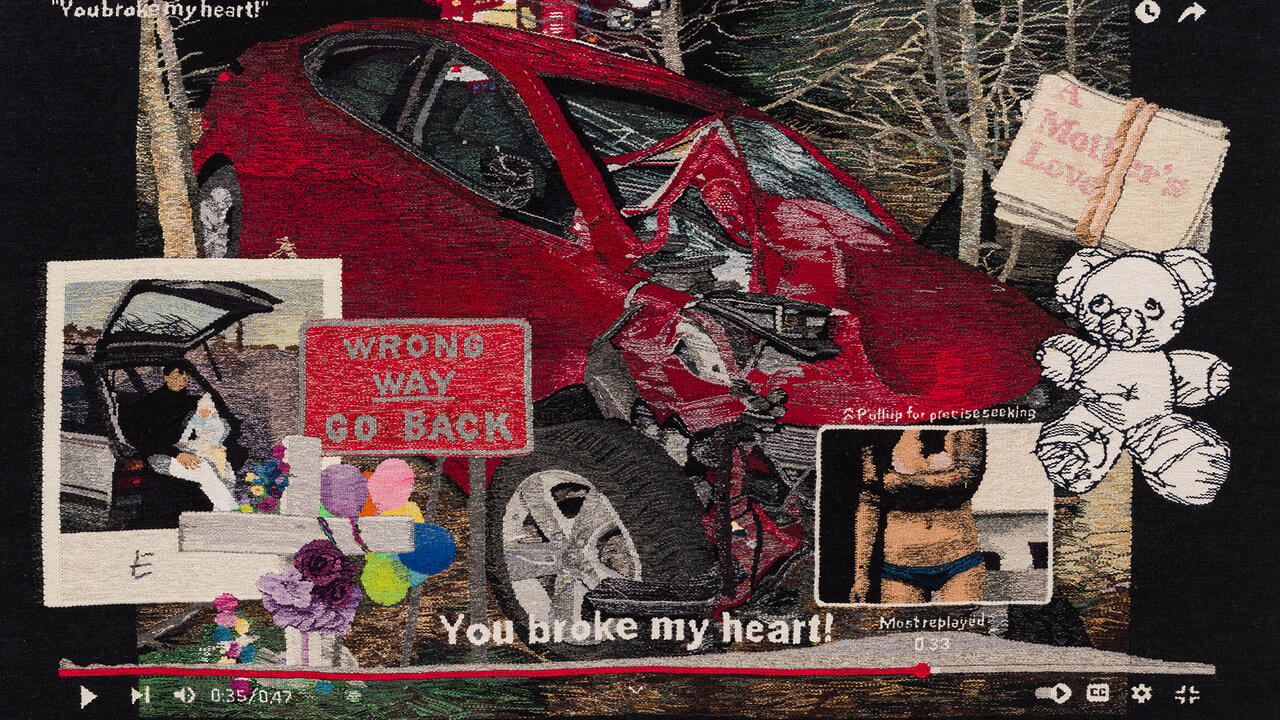

One of the newest works in the exhibition, Chicken of the Future (2019), is billed as a ‘far-fetched science-fiction-like solution for the world’s food problems’. All it would do (if it actually worked) is produce eggs; unlike an animal, it ‘has no unnecessary parts, no conscience, feels no pain’. Another, Gutenberg Press (2019), pays homage to the great innovator of movable type, but is equipped with a hundred tons of hydraulic power. Try to make a book on it, and you’re likely to crush the pages into dust. Looming at the other end of the gallery, meanwhile, is Pendulum (2019), another huge mechanism, bright yellow and equipped with ominous sandbag counterweights and a gong that clangs every quarter-hour. At 5pm every day, this doomsday clock will activate various ‘destruction machines’ scattered around the show, obliterating a range of everyday objects.

What does this all amount to, beyond apocalyptic theatrics and steampunk aesthetics (which, admittedly, Van Lieshout did help to invent)? Those inclined to see the artist as self-indulgent will find plenty to confirm their view here, particularly when he turns his imagination to issues of sexual desire. Witness a sperm-shaped architectural model for a Darwinian ‘luxury brothel’ in which women satiate their appetites with male prostitutes, of whom only the ‘cleverest, meanest, or strongest’ survive. Yuck.

For the most part, though, it is impossible to deny the depth and range of Van Lieshout’s provocations, or the constructive capacity of his Rotterdam atelier. The relationship between bodies and machines has captivated artists, social scientists and philosophers ever since the arrival of the factory system. Do the trade-offs that inevitably come with industry – dehumanizing work conditions, environmental calamity, the loss of traditions – justify themselves through increased prosperity? As our increasingly sophisticated tools extend our capabilities, are they also rendering us obsolete?

Most people don’t really want to face these difficult questions, but Van Lieshout won’t let us turn away. He forces us not just to think about the industrial condition, but actually feel it: that contradictory state of affairs in which the very things that give us vitality also torment our souls. It’s worth remembering that the era of the industrial revolution was also that of the Enlightenment, the so-called Age of Reason. Seen in light of that fateful conjunction, Van Lieshout’s unreasonableness makes all the sense in the world.

Main Image: Atelier Van Lieshout, ‘The CryptoFuturist and The New Tribal Labyrinth’, 2019, exhibition view. Courtesy: Pioneer Works, Brooklyn