Atiéna R. Kilfa Pays Homage to Film Noir

At Den Frie, Copenhagen, the artist deconstructs the genre’s archetypes to disarming effect

At Den Frie, Copenhagen, the artist deconstructs the genre’s archetypes to disarming effect

Rooted in German expressionist cinema, film noir is notable for its dramatic lighting, disorienting camera angles and entrenched sense of dread. The genre, which flourished in Hollywood during the 1940s and ’50s, captured something of the existential crises of the postwar years. Atiéna R. Kilfa’s film Rotor Vector (2024) – currently on view in her solo exhibition, ‘Special Effect’, at Den Frie – pays homage to the unease of the genre, starring a protagonist that could easily have stepped out of a sinister crime story.

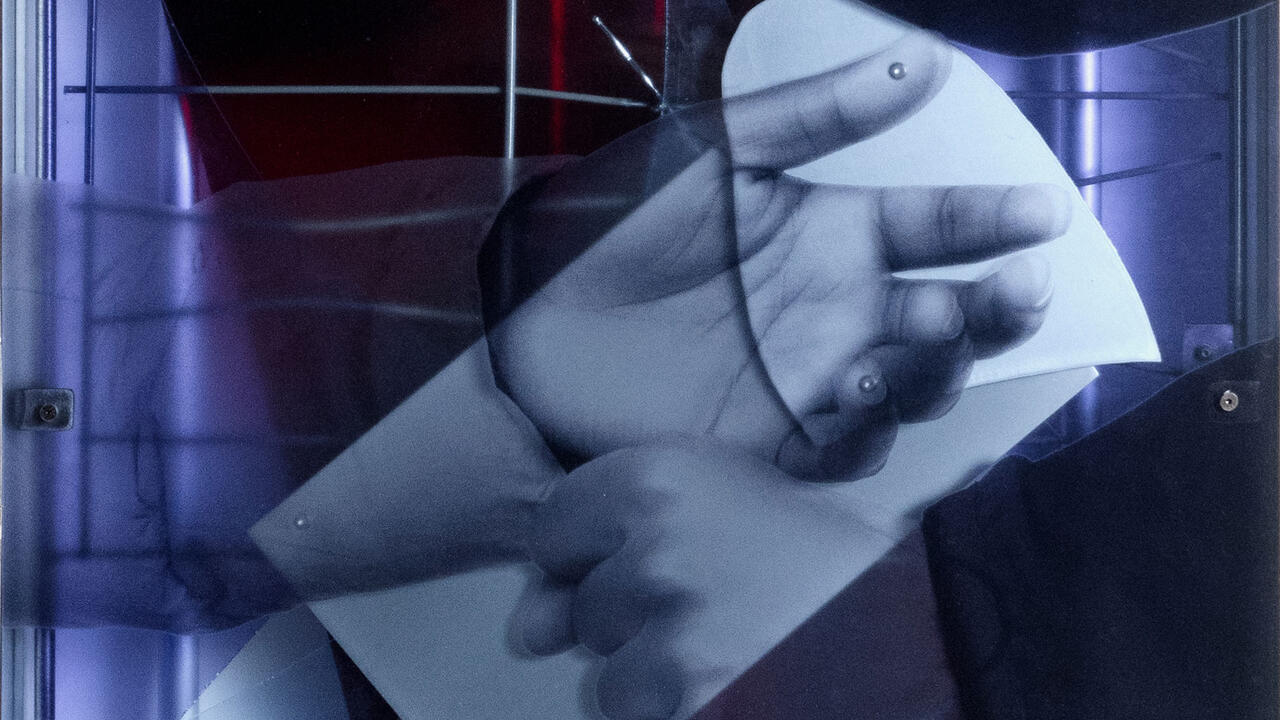

The grey-haired man dressed in a tuxedo and seated at a desk is the archetypal film noir gangster. As the camera zooms in, we find our attention drawn to details such as the folds of his shirt, the glasses resting on a newspaper, the deep creases around his eyes. The crisp black and white footage combined with the lack of soundtrack heighten our appreciation of this skilful piece of filmmaking, which, while undeniably beautiful, also carries a certain tension – as if the viewer has just been summoned to carry out an act of violent retribution against one of the man’s rivals.

The movement in Rotor Vector stems from the camera, which slowly pans across the scene and immerses the viewer in Kilfa’s minimalist set, featuring a desk, a filing cabinet and a greyscale backdrop of trees. The title itself refers to rotation about a point of origin – in this case, the male protagonist. Other tremors of movement add to the foreboding atmosphere: the flickering bulb of a table lamp; the bubbles rising in a glass of water. But Kilfa cripples any hint of a climax when the camera turns to reveal that the old man is, in fact, nothing more than a cut-out. There is a jarring moment when we realize that this is not the film nor the character we were expecting.

Kilfa is keenly interested in our perception of archetypes and what happens when those expectations are disrupted. In her film The Unhomely (2022–23), Kilfa delved into the architectures of home and the conventions of 1970s cinema. In Rotor Vector, she delights in upending our preconceived notions of the stereotypical macho criminal, using reimagined film noir techniques to unravel his identity. Whereas in The Unhomely, the actors that the artist filmed within an empty house recalled the stand-in humans of an architectural model, here, it is the cut-out that takes centre stage to surreal effect.

By leading the viewer to anticipate a certain outcome only ultimately to confound it, Rotor Vector inevitably draws comparisons to Sigmund Freud’s concept of the unheimlich or uncanny. The surreality of the doppelganger is heightened by the location of the screen itself, which is placed in the centre of the exhibition space, enabling the viewer to walk around – though never quite enter – the film. The leading man’s eyes seem to follow us as we move around the gallery. Two delicate drawings (Bedroom Floor and Living Room Floor, both 2024) elaborate on this negotiation of space. Using the frottage technique pioneered by Max Ernst in the 1920s, Kilfa produces rubbings of the floors from her previous and current homes that echo the handmade set construction and analogue filmmaking techniques of Rotor Vector.

Though the relationship between Kilfa’s film and drawings may not be immediately apparent, both have a focus on architecture and the performance of identity – whether within the film set tableau or the private space of the home. The real star in this show, however, is Rotor Vector, which leans into technical and cultural archetypes, only to deconstruct them to disarming effect.

Atiéna R. Kilfa’s ‘Special Effect’ is on view at Den Frie, Copenhagen, until 8 September

Main image: Atiéna R. Kilfa, Rotor Vector (detail), 2024, film still. Courtesy: the artist