Becky Beasley

Mute, restrained objects and photographs; eloquent but evasive literary references

Mute, restrained objects and photographs; eloquent but evasive literary references

No one symbolizes polite but unrelenting resistance like Bartleby the Scrivener, the famously stubborn copyist in Herman Melville’s eponymous 1853 story. Hired to proofread copied law documents, he soon refuses to verify the copies; he will only copy; and then, not even that. Eventually he refuses to move at all, simply repeating ‘I would prefer not to.’ He sits, ‘a perpetual sentry in the corner’, behind a ‘high green folding screen’, which his employer has procured to isolate Bartleby from his sight.

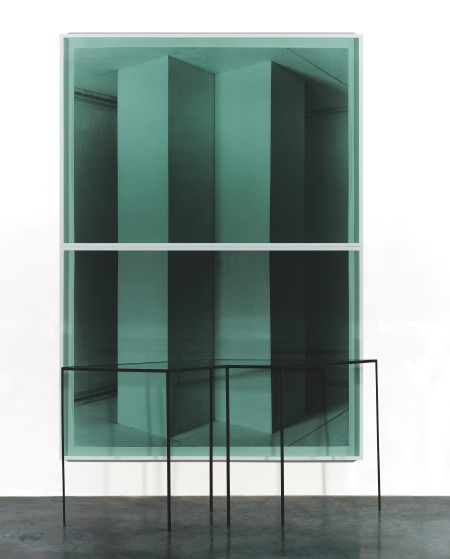

It is this passing description of the folding screen delimiting Bartleby’s semi-private work space that Becky Beasley draws upon in Literary Green (2009), two conjoined photographs that together produce a high-folded partition, mounted behind green glass, in front of which sits an acrylic glass table on delicate metal legs. A similar motif reappears in Glen Herbert Gold (2009), in which four wood-framed green-tinted acrylic glass panels stand upright, fanning outward from central brass hinges.

Beasley’s sculptures and photographs, as mute and minimal as they appear, unexpectedly open onto literary worlds: the screen behind which Bartleby sits; the coffin that a son constructs for his mother in William Faulkner’s As I Lay Dying (1930); the Steinway abandoned by the frustrated pianist in Austrian playwright and novelist Thomas Bernhard’s Der Untergeher (The Loser, 1983). In their respective novels, each signifies a construction that eventually becomes an obstruction to work. These imagined structures – emblems of impossible projects and the stubborn copyists (or artists) who undertake them – provide the models for Beasley’s art.

The artist’s work has gradually developed from murky photographic prints of found or featureless objects cloaked beneath cloth to photographs of wooden objects such as Gloss (2007), showing a shelf based on the dimensions of a piano; or images of coffin-like structures such as Sleep, Night 2 (2007); slipcases for books or boxes for letters made of acacia wood and black glass, which appear as empty vessels but are usually sealed shut; and a series of wooden ‘Planks’ (2008) that lie on the floor or against the wall, like sleds or slabs for dead bodies. Each one of these works has the solemn, monolithic quality of a headstone or a tomb.

We might never know more about these inscrutable pieces if it weren’t for the thorough yet elusive referential structure Beasley builds around her work in her writings and publications. Through factual histories of her materials, contributions from writers and her own essays, she constructs parallel narratives, urging the reader to look outside of her work – and the world of visual art entirely – to track down descriptions of fictional constructions imagined by other authors. Her most recent publication, Thomas Bernard Malamud (2009), whose title combines the names of two of her literary ‘guides’ – Thomas Bernhard and the Jewish-American novelist Bernard Malamud – is a companion to her show ‘German Soup’ (2009) at Laura Bartlett Gallery in London, and, retrospectively, her previous show ‘Malamud’ (2008) at Office Baroque Gallery in Antwerp. Both catalogue and artist’s book, it contains everything from a short history of her favoured material, American walnut wood, to an extensive essay on her interest in Bernhard; yet she skips over any mention of Malamud. Like a family album packed with documentation but lacking any picture of the photographer, it suggests more than it reveals, telling us little about the artist herself.

Formally resembling her series ‘Figures’ (2008), Beasley’s new series, ‘Brocken’ (2009) (which she translates from German as ‘scraps’ or ‘mottoes’) consists of several hinged planks mounted on the wall like shallow shelves. She apparently measured these wooden pieces according to the arm span of her father, with hinges placed where his joints would be. Because of the relation between age, arm span and height, the gallery text explains, ‘a child cannot measure their own grave, an adolescent could, but the fit would be too tight, whilst an adult’s arm span would produce a size into which they would comfortably fit.’ Beasley seems to suggest that the ‘Brocken’, are, in fact, measurements for the length of her father’s grave, illustrating what she might have meant when she said: ‘I want to propose something more distancing which is nevertheless very close, too close almost.’

There’s a vast disparity between the stubbornly minimal, blank look of her sculptures and photographs and the elaborate chain of mutable references Beasley offers us, which might explain her works, but certainly don’t interpret them. Her images remind us that a photograph can’t talk to us about its subjects’ origins or circumstances. Likewise, her sculptures aren’t merely depictions of a long plank or a wooden shelf. Instead they conjure up the hammering of the son who constructs his mother’s coffin, the silent room where Bartleby refuses to work, or the piano destroyed by the frustrated artist. If you were to come back to the artist’s works after chasing their literary sources, hoping to find the reasons why she might do this – why this object? why that reference? – Beasley politely refuses to give any more away. She could, but, like Bartleby, she simply prefers not to.