Cady Noland’s American Nightmare

A rare survey at Museum für Moderne Kunst, Frankfurt, demonstrates how the overlapping of dream and nightmare is far from exclusive to the US

A rare survey at Museum für Moderne Kunst, Frankfurt, demonstrates how the overlapping of dream and nightmare is far from exclusive to the US

Hans Hollein’s postmodern design for Frankfurt’s Museum für Moderne Kunst, which opened in 1991, has been compared to a gigantic slice of cake and a beached aircraft carrier. Its asymmetrical interior, with dramatically tapering sequences of rooms, niches and staircases, offers sightlines that bear comparison to an M.C. Escher print. Is it possible that the spectacular way the architecture comes into its own in this major Cady Noland exhibition curated by Susanne Pfeffer has to do with its postmodern character? For theorist Stuart Hall, postmodernism was not least about ‘how the world dreams itself to be “American”’. Noland, who withdrew from exhibiting in the late ’90s, has a reputation for creating critical visions of the American nightmare. In this exhibition, then, we seem to be wandering through at least two dreams, nested within one another, dealing with one and the same thing.

The show opens with the uncanny Publyck Sculpture (1994): a rudimentary children’s swing made of an angular aluminium frame, chains and three whitewall tyres, the kind associated with American cars of the 1950s and ‘60s. The setup evokes bars, fences or the playthings installed in zoo enclosures for bears and primates. Tyres and car-related objects – rear-view mirror, exhaust pipe, oilcan – recur throughout the show, though not as a sentimental homage to the freedom via mobility promised by modern American leisure culture. In one of the upper rooms, Pfeffer has hung Andy Warhol’s White Disaster II (White Burning Car II) (1963) from his ‘Death and Disaster’ series – bleak works incorporating photographs of deaths linked to technical equipment such as automobiles or the electric chair.

Like Warhol’s, Noland’s art examines American media culture and the disturbing effects of its economic structure. Warhol’s much-quoted ‘fifteen minutes of fame’ can befall a person in very different ways, on the way up or the way down, as in the cases of John F. Kennedy-assassin Lee Harvey Oswald or the Manson family. In light of current scandals, such as the one surrounding YouTube star Logan Paul, who recently filmed himself with the corpse of a suicide, the morbidity of a work like Celebrity Trash Spill (1989) appears far from outdated. On the floor we see a copy of the New York Post from April 1989 with a headline announcing the death of the left-wing activist and Steal This Book! (1971) author Abbie Hoffman, various magazines, cameras and camera gear, tripods, a microphone, a sparkly skirt, sunglasses, a sleep mask, a rug, two doormats and a Marlboro cigarette pack. The sad practice of rummaging through celebrity garbage traditionally counts among the more harmless activities of paparazzi and gossip reporters.

In her essay ‘Towards a Metalanguage of Evil’ (1987/1992), Noland quotes the psychoanalyst Ethel Person, who wrote that ‘the psychopath shares the societally sanctioned characteristics of the entrepreneurial male’ except that the psychopath happens to be ‘louder’. Noland produced these works two to three decades ago; in our own time, a real-estate speculator surrounded by sex scandals, a reality TV star and organizer of beauty pageants has become the presidential figurehead of a neo-puritanical politics that courts anti-abortionists, restricts the rights of transsexuals and seeks to pack the Supreme Court with ultraconservative judges. His means of exercising power include public shaming and humiliation, as traditionally embodied in the object of the pillory – an object found in works such as Tower of Terror (1993) and Gibbet (1993–94), alongside handcuffs, beer cans and American flags. Such works have an eerie prescience, despite their age. Our caustic present, it seems, has simply swallowed the fainted glaze of the historical. Yet part of what this exhibition demonstrates is how such an overlapping of dream and nightmare is not exclusive to the United States. As in a mirror, such disquieting practices may be closer than they appear.

Translated by Nicholas Grindell

'Cady Noland' is on view at Museum für Moderne Kunst, Frankfurt, until 31 March 2019.

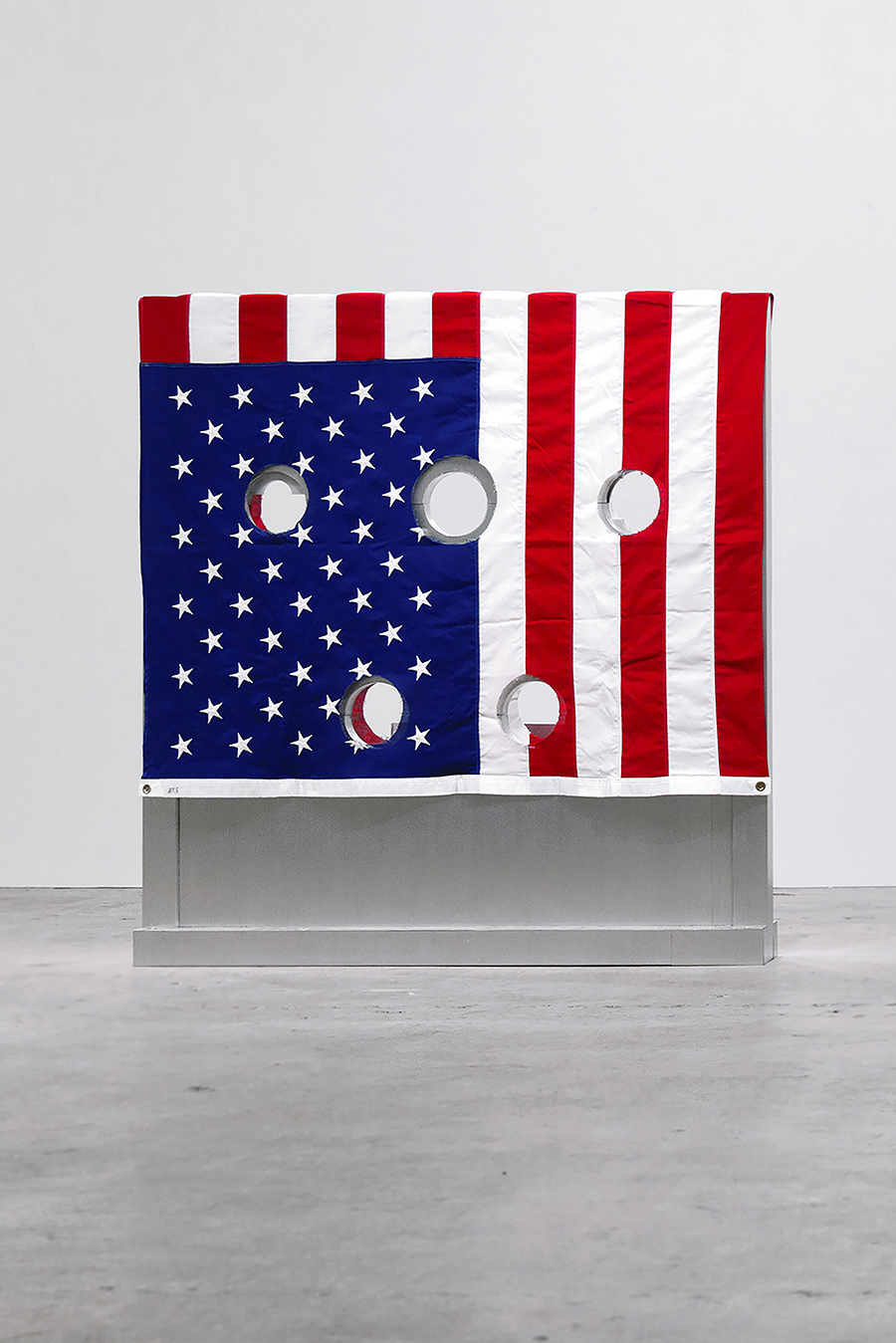

Main image: Cady Noland, The Mirror Device, 1987. Courtesy: Larry Gagosian; photograph: Axel Schneider