Candice Breitz

KOW, Berlin, Germany

KOW, Berlin, Germany

Candice Breitz’s ‘Love Story’ makes the most of KOW’s brutalist gallery space. On entering the first floor, you are presented with Profile (2017), a short film in which a diverse array of speakers claims to be the South African artist, making contradictory statements about her identity: ‘My name is Candice Breitz’, ‘I am a boy’, ‘I’m black’, ‘I am white as Tipp-Ex’. It keys you in to the show’s central conceit: notions of identity challenged by people telling stories that are not their own. But already, you can see down onto the ground floor, where booming voices emanate from behind a black curtain the height of a two-storey house.

Behind the curtain, you are confronted with a cinema-sized screen showing actors Alec Baldwin and Julianne Moore performing refugee narratives. Love Story (2016) cuts with bewildering speed between the actors and the disparate stories they tell, but after a few minutes, six discrete narratives emerge: a transgender hijra from India; a gay Venezuelan academic; a female swimmer from Syria; an atheist from Somalia; a former child soldier from Angola; a victim of sexual violence from the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Moore and Baldwin sit in director’s chairs in front of green-screens and tell these stories directly to the camera, asking the interviewer questions, producing tears, referring to themselves in the third person: ‘Alec, people will listen to you. You’re famous.’

As we listen, the stories intertwine thematically, from perilous Mediterranean crossings and political violence, to doubts about the interview process itself. But just as you begin to make sense of the narratives, you notice tiny spot-the-difference changes between scenes. Moore wears a heavily bejewelled bangle, but a few frames later it’s gone. Baldwin is wearing sunglasses, then an allergy bracelet and a small gold brooch, then a leather wristband. You become disconcerted by tiny differences between shots that you can’t quite believe have been staged: red eyes, Vaseline-covered lips, stubble missed while shaving.

Descending into a dark basement, you meet, on smaller screens, the six refugees whose stories are being performed above. The way you encounter their ‘real’ narratives has been completely changed by what you have just experienced. The refugees have taken on a subtle celebrity; before you hear them speak, you recognise them by the jewelled bracelet, the sunglasses, the brooch. As they tell you their stories, you are forced to compare the real speakers with those you had imagined when listening to the actors above. The idiosyncrasies of their spoken English have been edited out in Baldwin and Moore’s performances, making you aware of the extent to which specific voices prejudice your understanding of a given story. And as you face Shabeena Saveri (a transgender hijra, but also a smartly dressed academic) and Sarah Mardini (a swimmer and Syrian refugee, but also an ostensibly typical German teenager with long hair and a denim jacket), the subtleties of your prejudice are highlighted further. Your sense of authenticity has also been changed. Set once more in front of green-screens that allude to the artificiality of film, these ‘authentic’ narratives also feel staged somehow, because you are now primed to notice how mediated a recorded interview really is.

The concept of privileged, white American film stars speaking the words of real refugees, and thus making us reflect on who we listen to and why, has the potential to be, if not offensively simplistic, then certainly unsubtle. But Breitz transcends the potential for banality by not presenting her work as a closed statement. At an hour and a quarter, visitors might sit through Moore and Baldwin’s film, but not the 22 hours of footage in the basement. This means that even the most committed visitor, having heard everything the stars have to say, is forced to abandon the real speakers before they have finished telling their stories. It is a necessarily uncomfortable experience in an unexpectedly subtle exhibition.

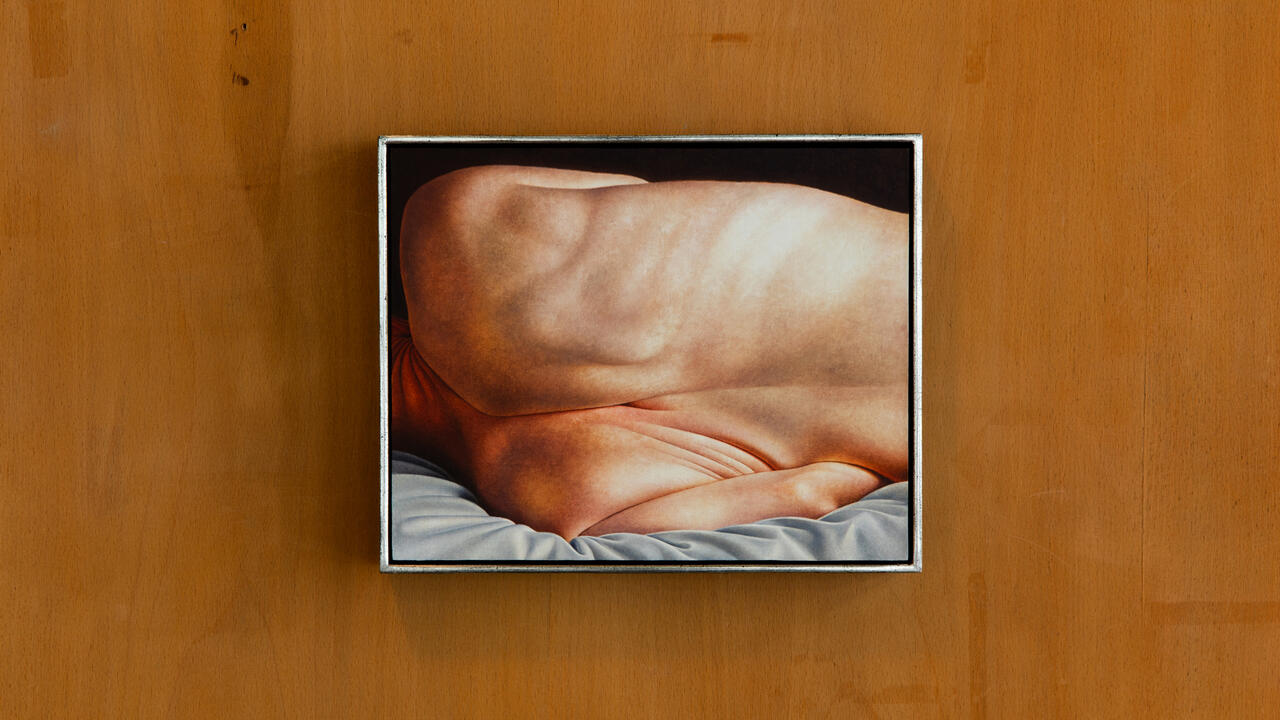

Candice Breitz, Love Story (still), 2016, 7-Channel Installation, Farah Abdi Mohammed. Courtesy: the artist and KOW, Berlin