Carl Cheng Makes Art for the Anthropocene

The meeting of environment and technology is front and centre in the Californian artist’s retrospective at Institute of Contemporary Art, Philadelphia

The meeting of environment and technology is front and centre in the Californian artist’s retrospective at Institute of Contemporary Art, Philadelphia

On the last March weekend of 1988, visitors to Santa Monica State Beach witnessed something peculiar: a 14-tonne concrete roller, Carl Cheng’s Santa Monica Art Tool (1988), embossing the sand with an aerial view of a Los Angeles-inspired metropolis. Titled Walk on L.A., the topography teemed with cars, motorways, buildings and handprints (a tongue-in-cheek gesture, since Cheng’s artmaking ‘tools’, which yoke his industrial-design acumen to conceptual projects, minimize evidence of his hand). As beachgoers realized the work’s titular directive, the cityscape dissolved back into sand. Periodically activated until 2007, Cheng’s project challenged the prevailing vision of public art – and land art – as permanent, static and monumental. Its ephemerality – an allusion to the precarity of California’s coastal infrastructure amid anthropogenic climate change – feels particularly poignant today, as Los Angeles grapples with the aftermath of devastating wildfires.

Documentation of this piece overtakes a wall in Cheng’s first major traveling survey, currently showing at Institute of Contemporary Art, Philadelphia. (The Californian artist, now in his 80s, will also participate in the Hammer Museum’s ‘Made in L.A.’ biennial this autumn.) While the works on view take forms as varied as moulded-plastic photographs, coin-operated dioramas, video installations and a greenhouse, they consistently convey certain bedrock principles: nature is dynamic; natural processes are technologies; technologies are part of nature; and, as the show’s title asserts, ‘Nature Never Loses’.

Cheng incorporated as John Doe Co. – evoking agricultural machinery and a white-coded moniker – in the latter half of the 1960s: before the rise of the artist-as-corporation, but around the time that artists were becoming involved with industry through programmes like Experiments in Art and Technology. Characterized by Cheng as a ‘new product’ in an informational card, Early Warning System (1967–2024) features translucent blue plastic cubes stacked atop a bed of wheat. As a distorted, projected montage of landfill and oil spills unfolds near the structure’s apex, a radio plays local live marine weather reports. Though the scratchy sound verged on indiscernible during my visit, the warning is unmistakable.

Cheng may be attuned to the realities of the anthropocene, but he doesn’t make the mistake of portraying the environment as merely acted-upon. A black and white snapshot, labelled Nature Laboratory (1966–90), shows an array of sundry objects, found or moulded, that Cheng left on his studio roof to be carved by the elements. These natural processes, which humans have historically mimicked and harnessed, reappear in a controlled context with his ‘Erosion Machines’ (1969–2020), two examples of which are on view. Conjuring up such contemporaneous, systems-minded works as Hans Haacke’s Condensation Cube (1963–67), Cheng’s fluorescent, laboratory microwave-style contraptions feature what the artist calls ‘human rocks’ – amalgamations of plaster and found-object fragments – being gradually eroded by steady streams of water. There is an uncanny affinity between these formations and plastiglomerates: 21st-century rocks that form when molten plastic trash fuses with rock, shell and other natural materials, an instance of the anthropocene sculpting itself. The notion that technology is somehow ‘outside’ of nature, Cheng reminds us, is a convenient fiction; in Anthropocene Landscape 2 (2006), green, brown and golden circuit boards arranged on aluminium re-create an aerial view of a landscape, gesturing to the extractivism that underlies the devices to which we are so beholden.

Artworks throughout the show – even those made six decades ago – look and feel startlingly contemporary. It’s prudent to be sceptical about the impulse to overpraise an artist’s prescience, as if the ability to anticipate the future (or future ‘turns’ in artmaking) is what confers art’s importance. But it’s also true that what we call foresight often comes from the hard work of attending to, and articulating, the world around you in the present – and, at that, Cheng has always been remarkable.

Carl Cheng, ‘Nature Never Loses’ is on view at the Institute of Contemporary Art, Philadelphia until 6 April 2025

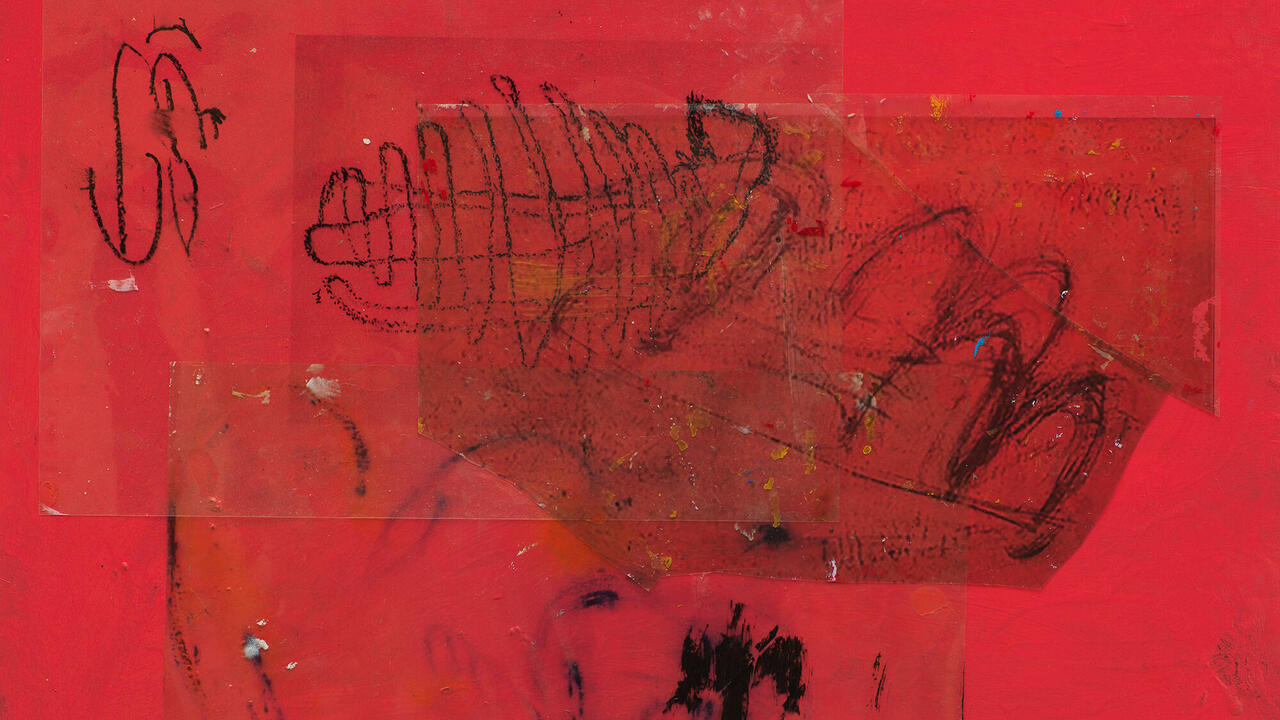

Main image: Carl Cheng, Human Landscapes—Imaginary Landscape 1 (detail), 2025, in Carl Cheng, ‘Nature Never Loses’, 2025, exhibition view. Courtesy: Institute of Contemporary Art, Philadelphia; photograph: Constance Mensch