Caspar Heinemann’s Revisionist Elegy to the Unabomber

An exhibition in Paris dabbles in speculative fiction inspired by FBI photos taken in Ted Kaczynski’s cabin

An exhibition in Paris dabbles in speculative fiction inspired by FBI photos taken in Ted Kaczynski’s cabin

In FBI photos taken inside Unabomber Ted Kaczynski’s cabin shortly after his arrest in 1996, a small box of Tide laundry detergent can be seen resting on a dusty workbench. Oddly conspicuous, tilted toward the camera, it’s the perfect Barthesian punctum – trivial as evidence, yet inescapable, its bullseye logo, like the Looney Tunes title card, bores a tunnel into the image. The thought of Kaczynski doing his laundry offers an alternative to the various popular depictions of him (murderer, hermit, incel, mad genius, technophobe, revolutionary). Briefly, he’s just another person participating in unheroic, life-sustaining drudgery.

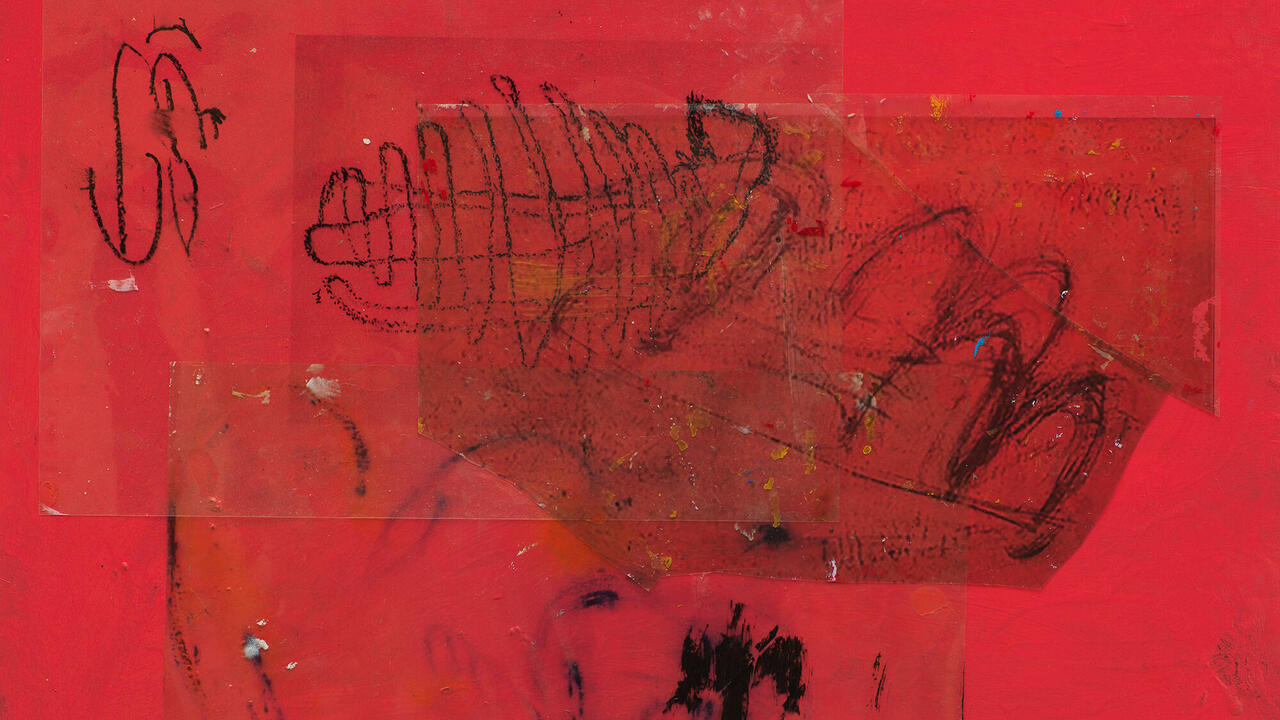

In Caspar Heinemann’s pen, ink and pencil drawing Rising Tide (all works 2023), Kaczynski’s soap box receives a closeup, appearing spot-lit mid-pour, white crystal powder cascading in a dramatic waterfall. The work features in ‘The Frayed White Collar’ at Edouard Montassut, Heinemann’s polyvalent revisionist elegy to Kaczynski. Other drawings, such as Theodora and Her Cabin (Interior), allude to the police’s famous composite sketch, in which the Unabomber appeared hooded, moustached and wearing oversized aviator sunglasses. Heinemann’s drawings, however, reimagine Kaczynski as Theodora, a trans woman living out a parallel life of solitude in the Stemple Pass cabin. The artist shows her checking her lipstick in a vanity mirror before heading out for a contemplative forest hike. In Theodora and Her Cabin (Exterior), she poses in front of her home like a cottage-core influencer, at ease and smiling, hair freshly blown-out, the aviators now less anonymous serial killer, more outdoorsy quaintrelle. Heinemann’s world-building originates from a brief episode Kaczynski recounted in his journals about having questioned his gender as a young person, leading to an unfruitful visit with a psychiatrist.

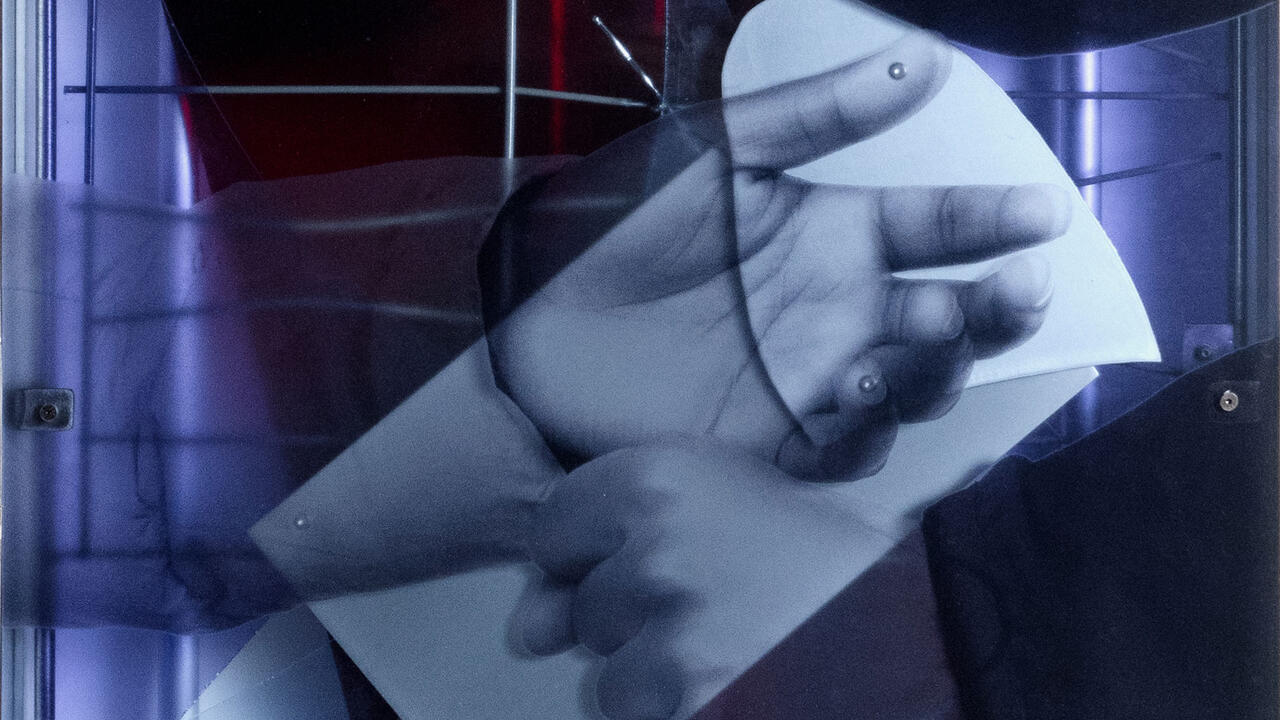

Further along, a wall-mounted sculpture (Grandfather’s Axe, 2023) assembles a kind of diorama out of wood scraps, miniature furniture, ornate wallpaper, electrical wire and one exquisite kitsch photograph of a topiary sculpture in the shape of Leonardo da Vinci’s The Last Supper (1495–98). Funny and strangely moving, the work deconstructs one of Kaczynski’s elaborate explosive devices to question what might’ve been had all that patient woodcraft and delicate ingenuity involved in bomb-building been channelled into a benign basement hobby, or even art – that is to say, a less violent means of coping with the despair and existential terror of modernity.

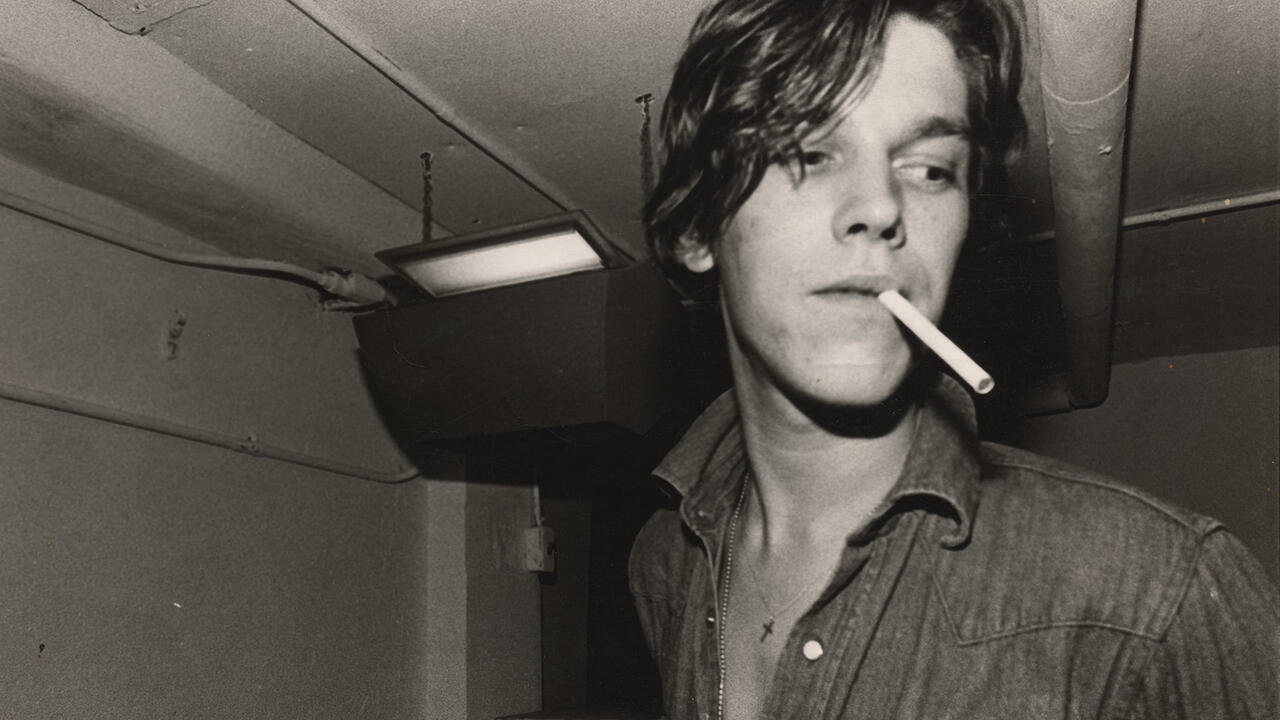

Heinemann’s self-portrait, Between Man and Man, complicates the reading. Stylistically, it’s a slight departure from the giddily overwrought and cartoonish collage of fact and fiction found in the other drawings, adopting instead a lightly worked sort of realism that looks to have been traced from an iPhone selfie. By dabbling in speculative fiction, which inherently demands wilful misreading and subjective over-identification, the artist places himself within the uneasy matrix of rage, yearning and solitude that made the Unabomber. It’s easy to wish Heinemann had elaborated, allowing ‘The Frayed White Collar’ to become the idiosyncratic melodrama teased in works like Rising Tide and the show’s beguiling title rather than a conceptual framework exploring the idea of a speculative fiction about Kaczynski.

An accompanying text reproduces an email correspondence between Heinemann and another artist, ‘Ed’, in which Heinemann details some plans for the show, including a breathless list of themes and references related to Kaczynski. Cheekily, Heinemann redacts all of these, blacking them out like the sensitive material in a declassified piece of evidence. In turn, ‘Ed’ praises Heinemann’s ‘refusal to calm interpretative panic’. With so many potential points of entry, though, we’re slightly left out in the cold as to the spark-inducing peculiarities of Heinemann’s empathic communion with Kaczynski. And so, we’re left to imagine our own.

Caspar Heinemann’s ‘The Frayed White Collar’ is at Edouard Montassut, Paris, until 27 January

Main image: Caspar Heinemann, Theodora and Her Cabin (Exterior), 2023; Rising Tide, 2023; Theodora and Her Cabin (Interior), 2023, pen, ink, and pencil on paper, 60 × 60 cm. Courtesy: the artist and Édouard Montassut