Celia Hempton

Galleria Lorcan O'Neill, Rome, Italy

Galleria Lorcan O'Neill, Rome, Italy

Removing four tiny glass bottles from her bag, each marked with a white label and containing thimbles of ochre-coloured liquid, Celia Hempton presents me with carefully blended fragrances that are meant to echo the scent of, well, a vagina. Meeting Hempton for the first time, there is something strangely and immediately personal about this exchange; in the most incongruous of settings, a busy café, I raise each bottle to my nose to experience these subtly sweet aromas that recall the most private of corporeal moments.

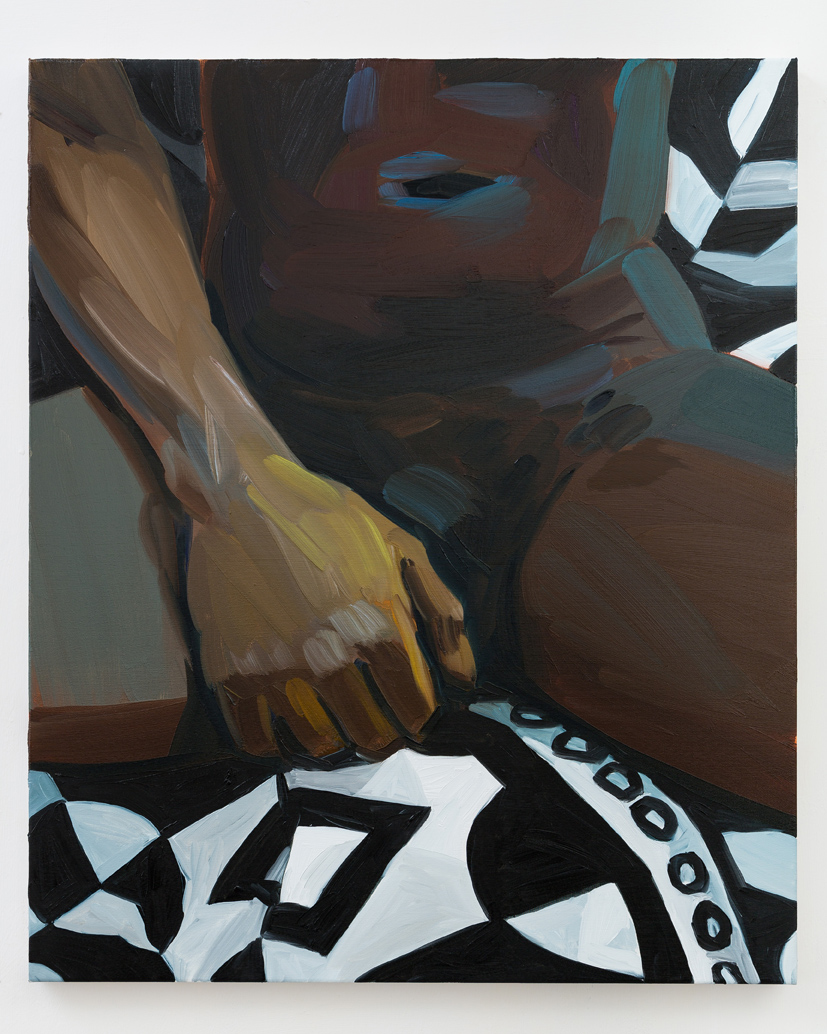

The London-based artist’s current exhibition (on until 30th June 2014) is equally as intimate, presenting 13 canvases that depict close up views of both male and female genitalia. Each painting has a bold, graphic register and is bathed in bright colour. Lemon yellow, pale pink, turquoise blue and lime green create a mood of warm vibrancy. This is flesh at its most appealing; rendered with delicate brush strokes glowing luminously with rainbow hues. A number of the canvases are installed upon background wall paintings; cool, hazy washes of patchwork colour providing a broader landscape in which the nude figures perform.

There is a confident, if not aggressive, overtone to the imagery, painted with candour and hung on the wall at eye level. Each canvas is titled with the name of the sitter – Eddie, Kamal, Justine, Caspar, Erasmus – evoking for the viewer something akin to a facial portrait, inverted. The artist produces each work from life, her models (often close friends) posing for hours at a time. She describes how there is an unequal vulnerability in this exchange, her eye scrupulously examining and reproducing these private parts.

The relationship between vulnerability, exposure and exhibitionism has been radically affected by the context of today’s hyperactive digital spaces – the curtain of the blue movie cinema has been replaced with a computer screen. How is this shifting attitudes towards flesh and sexuality for generation Web 2.0? A recent BBC survey revealed that one in four young people first view porn at the age of twelve or under. Hempton’s body of work titled ‘Chat Roulette’ (which will be exhibited at Southard Reid, London, in October 2014) responds to this development. Using the website chatroulette.com, which connects you via your webcam with other registered users at random, she ‘meets’ and paints anonymous subjects. Darker in both colour palette and atmosphere, these canvases become almost abstracted in their portrayal of flesh; pixilation blurs clarity, yellow and blue light recalls the glare of the computer screen at night within a grungy interior space. The artist describes how this ‘subject matter has a sense of wilderness or indifference about it — the interaction is less personal.’

By mediating the sexual encounter, making bodies and parts of bodies anonymous, does the internet depersonalize the sexual encounter? There is a strange irony about candid sexual material potentially forging states of isolation – the pornographic close up shot purposely cuts out the face from the act of fucking, excluding the part of the body by which a person is most usually recognizable. Hempton’s canvases at Lorcan O’Neill Gallery are individuated, painted from life, and seem to suggest a mode of countering this state; the purity of line, clean colour palette and sharp definition of works such as Jo (2014) seek to reactivate flesh – these are not deconstructed bodies, isolated organs, but the colourful and sensual private parts of people with names.

Gustav Courbet’s L’Origine du monde (1866), with its translucent pale skin exposed beneath thick dark hair, is called to mind as is Egon Schiele’s work, or nudes by Brücke artists Max Pechstein and Ernst Ludwig Kirchner. Hempton’s paintings build upon this history, problematizing the notion of the gendered gaze – Hempton speaks of different registers of sexuality and how ‘sometimes when I paint I feel like a girl, sometimes I feel like a boy.’ Are her images akin to Manet’s Olympia (1863), boldly claiming the autonomy of their subjects? The artist describes her interest in another work by Manet, The Ham (1880), delighting in its anthropomorphic character, suggested sexuality and visceral appeal.

The internet’s democratization of pornography has shifted the point of reference for the nude and artists are increasingly responding to this environment. In an age where we can see anything we want at the click of a button, Hempton’s paintings employ modes of detached voyeurism, or precise observation, to subversively reactivate the self and instill flesh with a sense of individual subjectivity.