A Century Ago, Tomorrow

In praise of the inventive brilliance of the late Guy Davenport

In praise of the inventive brilliance of the late Guy Davenport

A first-century Greek geographer writes of his wanderings through ancient Greece, misunderstanding everything he sees and hears. A demure servant takes a walk in the snow outside a sanatorium, leaving behind his life, miniscule hieroglyphics and small gems of literary compression. On 8 July 1581, the mayor of Bordeaux, ill with colic, writes a journal entry from his carriage noting that trees grow a ring every year – a good two centuries before it is discovered as scientific fact in 1774. An American in France cuts her hair short, in order to be modern, or like a Roman emperor. A Czech insurance agent sets his book, written in German, in the US, a place he has never seen, and where the Statue of Liberty hoists not her torch but a sword high up in the air. In the 20th century, two brothers from Ohio fly for 14 seconds on a machine modelled on both an insect and the kite that was used to discover electricity.

What ruddy wheels we whittle with words. They spin and crackle and when we make them new again we hardly get it right. Things come around too late, too early or not at all. The anachronisms of human invention, the fact that we walk onto the stage of creation off-cue, are central themes of the late Guy Davenport, a polymath teacher, visual artist and writer. Davenport – who once watched T.S. Eliot lift his feet to make room for an imaginary vacuum cleaner under Ezra Pound’s instruction – knew just about every artist of his era. (His correspondence, dotted with pencil drawings, counts over 2,300 names.) He wrote Oxford’s first dissertation on James Joyce and Harvard’s first on Pound; he has anecdotes about the ill-fated meeting of Joseph Cornell with the filmmaker Stan Brakhage. Yet Davenport, who lived quietly in Lexington, Kentucky, from 1963 to his death in 2005, was known as a professor, a peripatetic walker, a hater of automobiles and – by the children of his town – as a famous painter, which he wasn’t.

‘Understanding is common to all, yet each man acts as if his intelligence were private and all his own.’ This is Davenport transposing Herakleitos. The notion that we are never alone when we make things, resembles, too, the observations of Claude Lévi-Strauss, whom Davenport quotes: ‘When he claims to be solitary, the artist lulls himself in a perhaps fruitful illusion.’ An undercurrent to Davenport’s essays – on scientist Louis Agassiz or on Charles Ives’s music – is hidden kinship, above all between the modern and the archaic, and that accidents and serendipity are twins. We learn that E.E. Cummings’s poetic visage ‘l(oo)k’, in which the word ‘looks’ at you like two eyes, resembles an incomplete Greek papyrus fragment (‘l[oo]k’) as reconstructed by scholars; Cummings majored in Greek at Harvard. We learn, too, that the ancient amphora so admired by John Keats was knocked over by a vegetable grocer. And that, during World War 1, a well-known poet was reading to a brigade of soldiers when she forgot the words of the poem ‘Trees’ (‘What can explain a thing as lovely as a tree’), and was answered by an infantryman in the crowd, who knew it by heart because he was its author, Joyce Kilmer. In the early 1960s, Elisabeth Mann Borgese, the youngest daughter of Thomas Mann, became famous because Arli, her English setter, typed out the words ‘bed a cat’. We learn, too, that the Early English Text Society thought we should say ‘sunprint’ for photograph, ‘inwit’ for conscience, ‘wordhoard’ for vocabulary.

‘Why can’t I be just a plain modernist?’ Davenport once asked. ‘Aren’t I old enough?’ Perhaps the best way to understand Davenport’s essays (one about the painter Balthus is written in quatrains) or stories is through techniques we know from modernist art and poetry: collage, verbal assemblage, anachronism or the ‘subject rhymes’ and prose ideograms of Pound. Fragments of a wonderfully roving conversation Davenport had with Samuel Beckett in a churchyard in Paris, translations into Latin of R. Buckminster Fuller, or reflections about light in art history all appear, effortlessly, in his stories: ‘Vermeer was windowlight reflected from canals. Hobbema, the light before rain. The north had all its light sifted through forest leaves, and has never forgotten it. Only Durer dreamed of real light.’ This quote is from the novella The Dawn in Erewhon (1974), whose title slants a painting of Wyndham Lewis with Samuel Butler’s Erewhon (1872).

All of Davenport’s writing embodies this dream of innocent sleep.

In Lexington, Davenport formed part of a group of friends and artists that included Thomas Merton – a Trappist monk and writer, who was once visited by the Dalai Lama – and the photographer Ralph Eugene Meatyard. For Davenport, art is ecumenical and, by separating the sister arts, we have devastatingly betrayed the original meaning of the Greek word graphein, which means at once ‘to write’ and ‘to draw’. Tatlin! (1974), Davenport’s first collection of stories, begins in Moscow in 1932, at the opening of Vladimir Tatlin’s exhibition of constructivist works at the People’s Museum of Decorative Arts. The show contains a glider called Letatlin, a ‘bird’s ossature with syndactyl wings for a man to fly in’. (Davenport’s lexicon is contained by no dictionary.) It then jumps back to 1905. The story, like all of Davenport’s output, connects artistic modernism with the discoveries or inventions of the archaic: Herakleitos saw ‘the complementarity of all things wrestling each other like athletes red with dust’; Niels Bohr stole his ‘hooked atoms’ from Demokritos; while Tatlin – like Da Vinci, the Wright brothers and literary invention itself – ‘had gone back to Daedalos’.

For Davenport, human invention knows no genre: it falls from time. His most famous book is titled Da Vinci’s Bicycle (1979); a later work, The Jules Verne Steam Balloon (1987), resonates with the same visionary anachronism. Every Force Evolves a Form (1987), a collection of essays, and the phrase written on Davenport’s gravestone, was borrowed – while sounding, Davenport notes, like the words of Walter Gropius or Le Corbusier – from Mother Ann Lee, the founder of the Shakers and, incidentally, the inventor of the modern broom. (‘There is no dirt in heaven!’) Modernism may have been too committed to canons of accepted men but, in Davenport, for every Pound there’s a Eudora Welty, for every Gropius a Mother Ann Lee. In so many ways, Davenport, who was the last great amateur – in the old sense of the word, meaning someone who simply loves things – has more grain to him than a three-dimensional map, and more place names than a phone book.

I once phoned Bonnie Jean Cox, Davenport’s partner of 40 years – who herself appears in some of the stories, and who died in July – to get permission to quote a letter of his. She was excited that Davenport might be known in Germany, where I live. But Davenport is neither regional nor provincial. His works, written from no centre except that of the imagination, recall the fact that scientific discoveries, and certain poems and phrases, happen at the same time, inexplicably. They occur in the shape of a parabola, meeting but not touching. From parabola we get ‘parable’, which shares the Greek root ‘thrown beside’. The cubists made this ‘throwing-beside’ a split in perspective. (‘Picasso was prehistoric.’) ‘It was in 1914 that Wittgenstein began his tragic inquiry into the officiousness of language. Language, he saw, was a picture, and in 1913 pictures became language. Cubists wrote.’ Davenport inherits his parabolic, cubistic vision where anecdote, historical witness, apocrypha and improbable realities collide – resolutely modernist constructiveness and artifice reach up, and down, to primitive and archaic truths which, like shale or positrons, are hard, true and unstable, eternal and invented.

Davenport’s suspension of time shares a feature common to emergencies, idylls, stories and facts. ‘History’, Davenport has Robert Walser say in a story, ‘is a dream that strays into innocent sleep.’ All of Davenport’s writing embodies this dream of innocent sleep: the white clover, descending like butterflies over the snow. His is a collaged world (at once pastoral and parabolic) of Tatlin and loops of smoke, where neckties absorb wine like candlewicks, pocket neckerchiefs are as big as maps and hot air balloons are believed to be animals – all inventions which, in the truth of their history, are laid down too quietly and quickly into obsolescence, or just nearly.

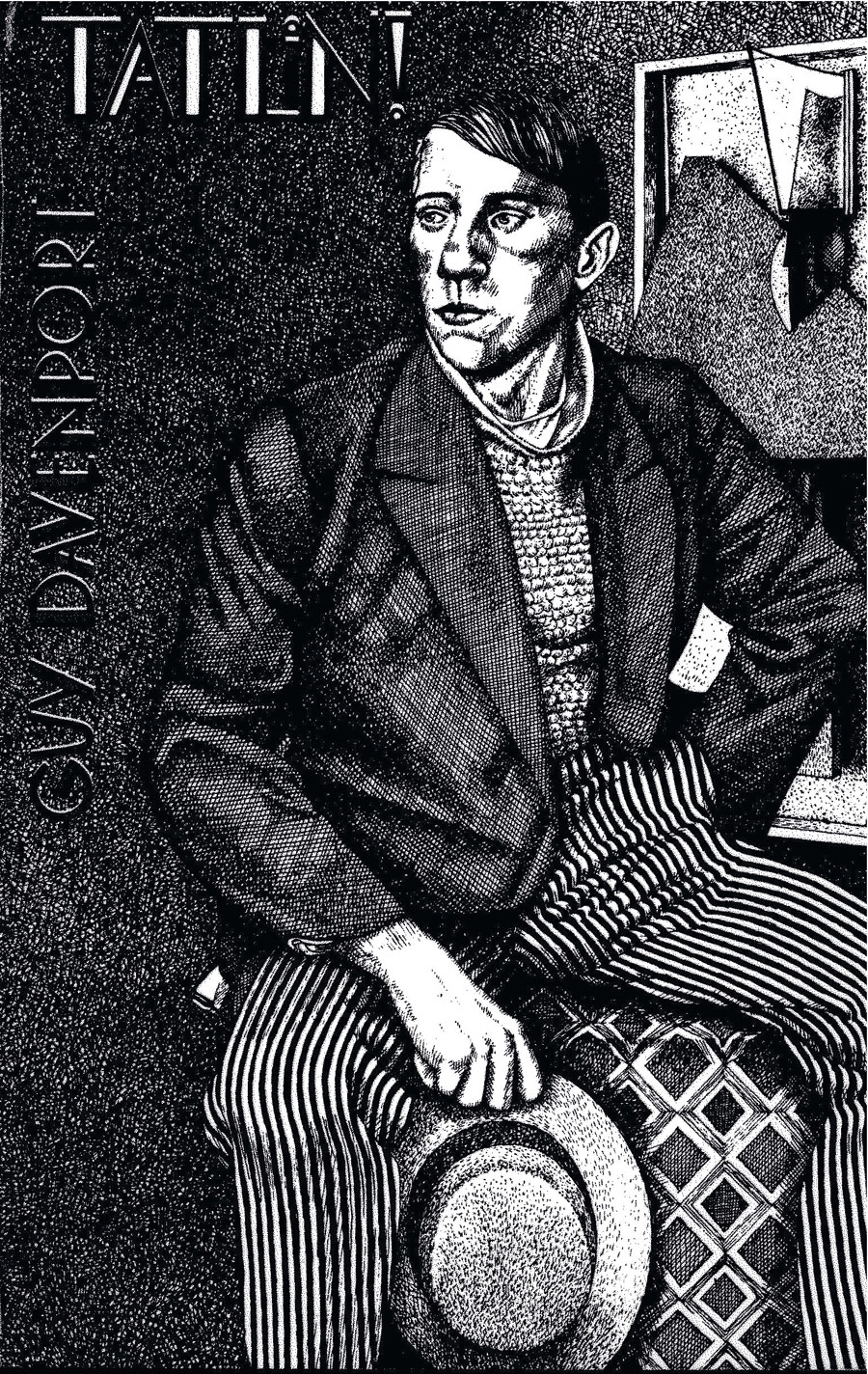

Main image: Guy Davenport, 1992. Courtesy: Counterpoint Press, Berkeley; photograph: Guy Mendes.