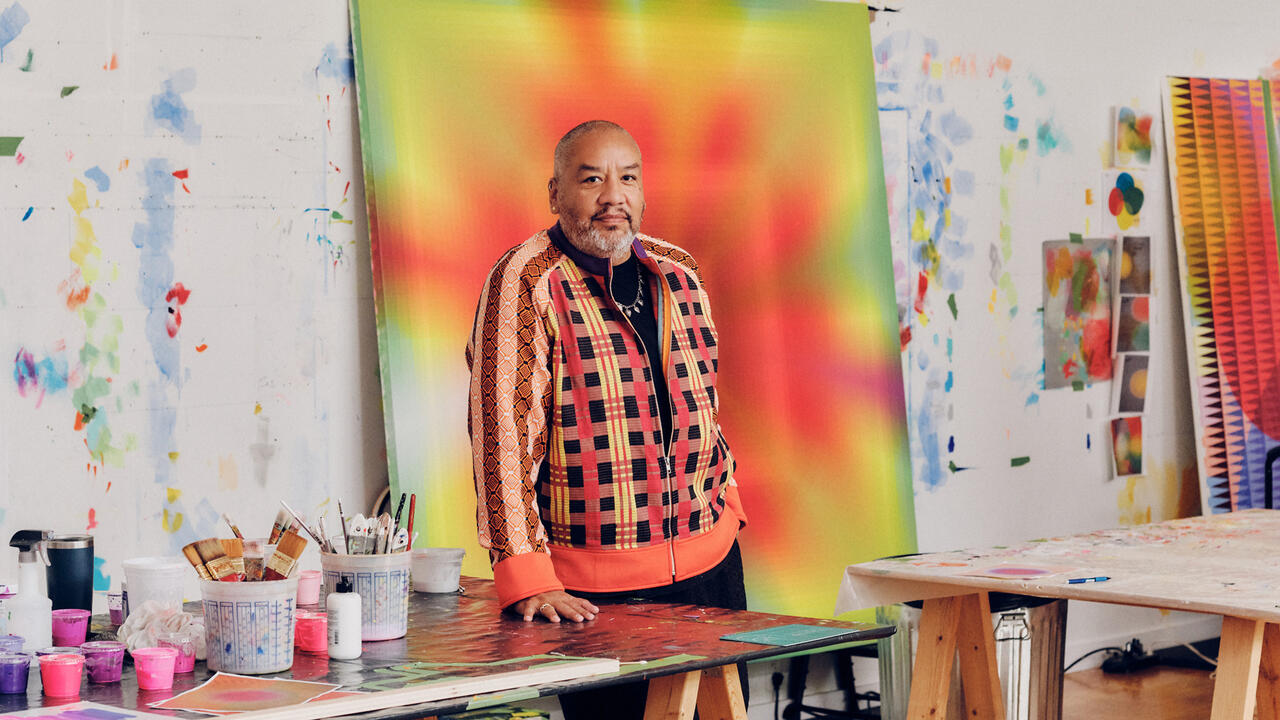

Chains of Love

With a solo presentation at Frieze London, Melvin Edwards discusses symbols, self-expression and his work in the Tate’s ‘Soul of a Nation’ show

With a solo presentation at Frieze London, Melvin Edwards discusses symbols, self-expression and his work in the Tate’s ‘Soul of a Nation’ show

Paul Teasdale Let’s begin by talking about your work included in ‘Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power’ currently on view at Tate Modern, London.

Melvin Edwards There are three works, from 1963, ’64 and ’65, I think. Those were the first years that I’d say my work clearly developed into something that was specifically mine and not referential to anything that I had learned or studied. The fourth work is from some years later, 1969, I guess was its origin, but very different in concept and form. A lot of my ideas come from those very early years, and have developed in parallels as opposed to sequentially. In other words, distinct attitudes about form and content sometimes reference each other, but sometimes they don’t. It’s not necessarily chronological.

PT In terms of references, are you an artist who surrounds himself with images of works that you’ve seen, or perhaps things that you have noticed?

ME I read a lot, I look a lot, but I don’t reference other works in my work. I never have. My basic training was in painting, not sculpture. I took the required sculpture class, which was the traditional model on a stand in front of you, and you worked representationally, and that was that. I spent 1955 to 1960, which were my basic years in university [at the University of Southern California], primarily as a painter. I thought I was pretty much a hotshot painter, actually.

Truthfully, I was confident that it could have developed good ideas in painting, because I had developed changes in my own thinking about what I was interested in, and they naturally went away from figuration, which was everybody’s training then, and into abstraction – not that it was something encouraged in school.

I’ve always thought that art should ultimately be personal. And that’s really been my focus: how to keep it personal. It may be validating for other people to find that your work reminds them of something else, but it’s much more important for me to keep myself alive creatively, to have the point of departure for whatever I develop be personal. In a sense, that’s been part of the basis of how I work.

I guess it’s like theme and variation, if you were discussing music. You invent a theme, you develop a variation on that theme, and then you take that variation as a beginning point for the next variation and so on. So in abstract processes, you get far away from wherever you might have started. And if you have multiple starting points, you just have a lot of space to make art. That’s why my sculpture can have a range of extended social expression and yet be conceptually abstract at the same time.

PT When did you start working with sculpture?

ME I would say around 1959-60. I learned to weld in 1959. I saw a couple of graduate students welding, which in those years was very rare. Five years later, all the colleges and art schools had programmes in sculpture that included welding.

By 1965, I was teaching at the California Institute of the Arts, and a major part of the reason I was hired was because I knew how to weld. What they didn’t know was that I wasn’t that interested in teaching welding. I felt sculptors, like any artist, should find their own voices and the reasons why I make choices would not be the reasons for somebody else.

The artist who taught me how to weld was a graduate student at the time, a man named George Baker. He laid out six sticks of steel and gave me the fundamental methodology for joining them, and then basically said don’t bother me; you can do everything from this. Or if you can’t then you can teach yourself. He was working on his graduate exhibition and didn’t want to be disturbed.

PT Were you influenced by other artists at the time? Were artists in LA aware of what artists in New York were doing, for example?

ME The distance then from Los Angeles to New York was as great as it was from London to New York, in a sense. There wasn’t the means for influence as much as there was the space for getting a few notions and going with them. And that wasn’t just for me that was the situation for everybody.

One question that others have asked me, especially those from the UK, is did Anthony Caro have any influence on my work. And, you know, it sounds like a good question, but people who ask that question don’t understand the chronology. From what I’ve read, Caro started welding in 1959. Okay, well, I started welding in 1959! I was in Los Angeles and he was in London. But of course, he’s a generation older than me and you can certainly say his work gained prominence, but my own breakthroughs were without any knowledge of him, so it’s not a proper question for me. He simply was somebody else, working somewhere else – a fine artist, for sure, but nothing to do with me.

PT Perhaps an obvious point of difference but I sense a strong political interest, even a message, in your work. When did that start to inflect your art making?

ME Put it like this, I think about political issues in my life and always have, because the dynamics of politics, of social realities, have always been present. I grew up in the United States of Apartheid, in the South, where segregation was legal and absolute. I don’t remember meeting a white person before the age of seven, when I moved north to Ohio. Where I grew up in Houston there were black sections the size of towns, containing more than 50,000 people, with self-contained social infrastructure. My life as a very young person was very much inside the community of family and friends.

Then, in Ohio, where I lived for five years, all schools were integrated, so it was like American society in general, integrated but with racial dynamics under the surface. There was discrimination, but not really segregation.

It was only when we moved back to Texas, that I began to learn the world of segregation. But still, I went to a very good high school and had very good teachers – the same high school my parents had gone to. If it wasn’t the same teachers who had taught my parents, they were teachers who had gone to school with my parents. So it was a warm and dynamic community, and the education was very good.

When I went to California for university, I didn’t find any deficiencies in my education – the stereotypical limitations of intellect that people might assume because I had come from the South. California, and Los Angeles in particular, was a very dynamic city with a lot of things to learn. I knew art was the direction that I wanted to go but I didn’t know what it might consist of. (I probably had the teenage notion that I would be a painter and make lots of money, have a nice apartment and girlfriends.)

PT So art for you became a vehicle for self-expression, as a way of confronting lived realities?

ME In terms of socially expressive notions, they happened in the process of works that are essentially experimental. In other words, each work is an experiment in its own dynamics. And the titles don’t come first, you know. For me the subject matter is not explicit as it would be for somebody who illustrates. I’m more interested, first of all, that the work be expressive; that it be sculptural, three-dimensionally significant. I always feel that that combination of that and my own evaluation of what’s in front of me are the most important things.

No work of mine is set off by a particular incident, even though there may be references in titles to specific incidents. Titles of pieces such as Amandla (1981), which was the political theme of the African National Congress: well that was just to express some empathy and solidarity with the movement of people in South Africa to change that society. But it didn’t illustrate anything. I would, if anything, play with things symbolically – like in music, sounds make a difference.

As far as symbols go, there’s still multiple significance, in my works using chains, for instance. Many people jump to the notion that the primary reference is slavery but there are many other reasons to consider using that form, or variances of that form. If a traditional blacksmith anywhere in the world forged a chain, the important thing would be did he do it well? Was it well made? If it wasn’t made well, he wouldn’t be considered a good blacksmith.

Take the word ‘love’ – it’s in every poem in the world, practically, but you could say, ‘I’d love to kill you’. In other words, the meaning of the form, or the meaning of the element within a work, is affected by what the context is, what form is next to it, what form is under it or hidden by it. So you’ll find locks and chains and forks and knives or forms that enclose or do all of those things. I am interested in the dynamic side of sculpture more than the passive side. The simplest of my works are usually the ones that have barbed wire and chain and they’re linear, or they’re geometric. They deal with subtleties of patterns created by the light on the wall. All of this, the range of ways to manipulate the three-dimensional space that sculpture can occupy, is a part of what I play with.

PT You must have a deep affection for steel to work so consistently with it.

ME It’s becoming harder to do!

PT Right. Are you still in the studio every day?

ME For the most part. Unless I have to go somewhere or be somewhere else. Then I just make notes and little sketches of principles or concepts that I should investigate. But if I go anywhere for longer than a week, I have to find some way to make some kind of sculpture or some quick notation.

I have two studios, one in New Jersey, which I’ve had since 1976, and then one in upstate New York, which I need for more space, for the bigger land works I make. I also try to spend a couple of months of each year in Senegal, and there I spend time in the workshop of some metal fabricators. So really I have three places I’ve been working for the last 50 years.

PT I'm guessing you like the working environments that you’ve created, to have stayed with them for so long.

ME Well, ultimately, you know, your environment is your own mind. And while the places influence or corroborate or sometimes give special opportunities, for me a lot of times different environments have more to do with the opportunity to meet different people and understanding different approaches to life and culture. All of that is a bonus to me. For instance, I’ve been coming to England for years, not for my own art but attending literary events, because my late wife [Jayne Cortez] was a writer whose work was well known in London.

I’ve travelled many times to different African countries and to Mexico and Brazil. In the Afro Brazil Museum in São Paolo, there are five works of mine. I went to Japan in the ’90s because they awarded my work the grand prize at the Fujisankei Biennale. If you live in Los Angeles, the influence of Japanese and Asian art is in the air. So you might just say I have an interest in the world.

I think you could say the same about art making now. The Tate exhibition, while it’s only a segment of 20 years and there’s lots more to that reality, is a way of opening a door. People can get an idea of the developments, the significant differences within that community and within American art, and therefore within the world of art in general. My own connections have been as much with, say, Nigeria and Zimbabwe as anywhere else. I worked three summers in Zimbabwe; I’ve been going to Nigeria since 1970. So African art has been a part of my work. I found artists there from my own generation with similar – not the same, but similar – aspirations, as their societies were gaining independence and the opportunity arose to do something different. I just regret that there are artists of my generation in those countries that have not being given their dues. But life has those realities, you know.

PT Do you think the situation is starting to change?

ME Of course the world changes, yes. But the historical discussions need to be amplified and gone into in more depth. I mean, everybody’s happy, or happier, if more attention is being paid to their art. But if there are say 30 artists included in a survey show, I know at least 30 more who should also be. And that just means a healthy amount of activity has already been happening. And that’s to the good, because it argues that the future will be full of improvement.

‘Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power’ is on view at Tate Modern until 22 October 2017.

Melvin Edwards’s solo presentation with Stephen Friedman Gallery is on view at Frieze London 5- 8 October 2017.

Main image: Melvin Edwards, Oklahoma City, 2016. Courtesy: Alexander Gray Associates, New York; Stephen Friedman Gallery, London; photograph: Brandon Seekins