China’s Virtual Victory: from Typewriters to Huawei

China’s triumph over Western information technology is world-historical, not just a niche curiosity

China’s triumph over Western information technology is world-historical, not just a niche curiosity

An intriguing quote appears near the end of People’s Republic of Desire (2018), Hao Wu’s documentary about China’s widespread live-streaming platform, YY, where wealthy celebrity fans donate hundreds of thousands of dollars to their favourite stars, seeking admiration from poorer fans: ‘I don’t think this virtual world is that much different from real life, only that this platform helps to release some energy that is otherwise suppressed in real life,’ says Chen Zhou, YY’s CEO. Money is a source of enormous influence in contemporary China, he implies, much as it is in the US. But does competition between their tech industries also reflect broader differences between the powerhouse nations in real life?

New York’s Museum of Chinese in America’s recent exhibition, ‘Radical Machines: Chinese in the Information Age’, harkens back to an earlier moment in the development of Chinese commu-nications technology, when the language’s symbol-based script posed major challenges for movable type, Morse Code and typewriters. Chinese does not have an alphabet; each character has a unique meaning, and the measure of Chinese literacy is in knowing roughly 2,000 characters. This presents a singular problem: how to reduce this script into typeable components? A 19th-century European prototype cut up the strokes of the characters into further line fragments on a grid. Later, the Chinese typewriter boasted a heavy tray of 2,500 unique keys, requiring the typist to remember the location of each one. From the comic strips and video clips on display in ‘Radical Machines’, we are reminded that this technology was once seen as laughably complex in the West, a metaphor for China’s inability to enter the modern information age.

Then, typewriters became obsolete. Word processing, modern computing and new input systems – Pinyin, word prediction, touch screen handwriting, voice-to-text – brought Chinese typing to the masses. Today, as Thomas Mullaney points out in The Chinese Typewriter: A History (2017; the exhibition is based on this book), China is not only the largest IT market on the planet, but also ‘home to a script that is among the fastest and most successful within our era of electronic writing’.

YY and livestreaming are just one piece of a Chinese tech sector that is giving the US a serious run for its money; its social media platforms, like WeChat, are often more multi-functional, versatile and integrated than WhatsApp, Facebook or Instagram. Tencent, the social media giant that owns WeChat, is worth more than Facebook. Chinese companies are also setting sights on US consumers and American politicians are taking note. A 2017 bipartisan bill proposed expanding the jurisdiction of Cfius, which investigates mergers between foreign and US companies, but has mostly been targeting Chinese tech companies.

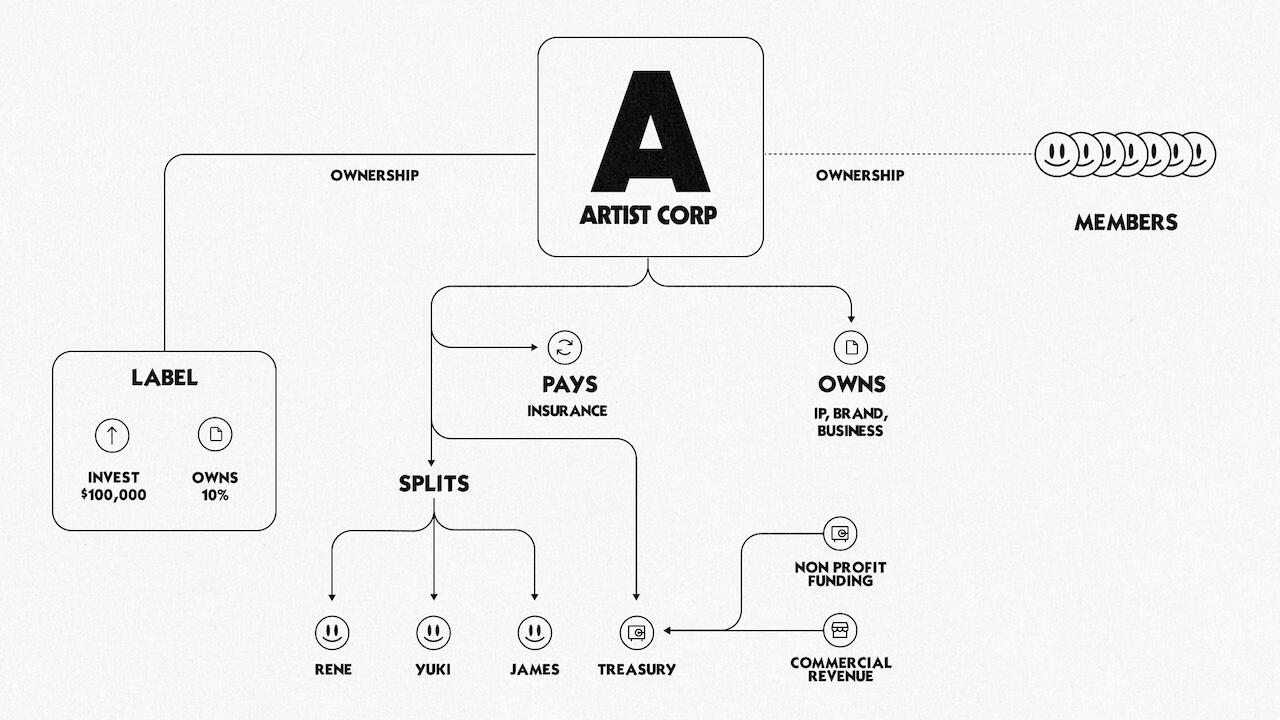

And China’s increasing dominance is the reason why its triumph over Western information technology is world-historical, not just a niche curiosity. It also makes it easier for US politicians to blame China for the economic insecurity and online privacy breaches that plague working Americans. But aren’t China’s tech-sector triumphs also a symptom of a global political and economic system that favours the rich and protects the power and profits of private companies? How much should it matter, for the average user, whether Apple or Huawei, Amazon or Alibaba, own the infrastructure of our networked future? And wouldn’t it matter just as much if regular users, fans or ‘influencers’ had greater control over these networks?

Each tech company is really just a player in the global multi-player game to dominate the economy of the future, with Israeli, Japanese and Canadian teams also vying for A-list rank. Whether the American or Chinese team emerges victorious could spell a shift in how we define online freedom: as an individual’s right (and, perhaps, duty) to spout whatever they please – conspiracy theories, hate speech, rants intended to sow widespread chaos and division – or as freedom from the tyranny of anonymous users, backed by wealthy interests or foreign states, who aim to manipulate public opinion. But this is no clash of civilizations. Ideology divides the two powerful regimes – neoliberal democracy vs. capitalist authoritarianism – but they also share something just as fundamental: agreement on the rules of the game. Victory, for any team, is measured by the scale of economic development.

‘Just like real estate in China, you never know the great potential of things to be developed,’ jokes the popular singer Shen Man in one of her YY broadcasts, in People’s Republic of Desire. ‘Likewise, you’ll be surprised once my flat chest gets “developed”.’ But with her webcam off, she is blunt about how ‘potential’ also corrodes real life. ‘Every girl wants to be a princess. But when money is involved – family, love, friendship, they’re all bullshit,’ she says. ‘People worship you if you are rich; nobody gives a damn if you are poor.’

This article first appeared in frieze issue 201 with the headline ‘Virtual Victory’

Main Image: BM Electric Chinese Typewriter brochure, 1913, included in ‘Radical Machines: Chinese in the Information Age’, 2018–19. Courtesy: Museum of Chinese in America, New York