Christian Marclay Wants Us to Stop, Look and Listen

The artist’s new show at White Cube combines structuralist filmmaking with the Green Cross Code, to dazzling effect

The artist’s new show at White Cube combines structuralist filmmaking with the Green Cross Code, to dazzling effect

‘Look!’ commands the first room of Christian Marclay’s luminous new exhibition at White Cube Mason’s Yard. Look left, look right. Stare at the worn lettering of ‘LOOK’ street signs from London’s pedestrian crossings: here, dissected by double yellow lines; there, admonishing from the depths of a puddle.

Recalling, in equal parts, Hollis Frampton’s structural filmmaking classic Zorns Lemma (1970) and British road-safety initiative the Green Cross Code, Marclay’s photographs take meaning from words that have been painted onto the city. The imperatives are brought together in a looping animation (Look, 2016–19), which circles through thousands of such images so that the word becomes a juddering cartoon on a flipbook of tarmac. It’s a similar tactic to the one Marclay adopted in 2016 with six animations of objects on roads, from cigarette butts to chewing gum: a literal ‘street photography’ of everyday detritus given structure through repetition.

Here, it’s a prelude to and an instruction for what comes next. Descending into White Cube’s subterranean space, the light of the ground floor is lost to a darkened gallery, lit solely by a floor-to-ceiling monolith of spasming colour. Step closer and you’ll see this imposing column is made up of 22 horizontal slithers, each cut from the very bottom of a film’s frame, where subtitles tend to reside. Subtitled (2019) is an exquisite corpse of fleeting slivers, with fragments of dialogue and closed captions flitting between glimpses of body parts, car chases, sea storms, burning buildings and an overflow of other images.

The films duck and weave continuously and, while the first impulse is to mentally climb this ladder of cut-outs, looking for the kinds of clear juxtapositions and narrative bleeding that Marclay carved so masterfully in The Clock (2010), the rungs here are greased. There are connections, divergences, convergences, but they are more of colour and geometry than any clear continuity of scene. If the hours of the day were the anchor for The Clock, here it is the rainbow, uncertain and flickering.

And silent. Sound has been a key part of Marclay’s film collages: a ligament for the disparate shots of music being made in Video Quartet (2002) or guns being fired in Crossfire (2007) or pretty much every transition in The Clock. Conversely, the flow of images in Subtitled has to make do without aural connective tissue. All the better for creating a cacophony, as directions for storms, words and whispers dance simultaneously on the screen, leaving us uncertain as to what is said and what is thought. ‘I love you totally, tenderly, tragically,’ one subtitle reads, separated by strips of roiling water from ‘(thunder)’, before both are immediately lost amid the deluge.

The artist has played with words and implied sound before: in Surround Sounds (2014–15), for example, onomatopoeic phrases from vintage comic books exploded and cascaded across gallery walls. Here, there is more restraint – and more power for it. Rather than overwhelm the piece, the closed captions form one part of the weave, moving from text to texture as the thin strips of film ripple between a tower of moments, like the windows of a skyscraper or 22 browser tabs open at the same time.

More than anything, however, Subtitled reminds me of a stained-glass window. Just like the religious imagery on stained glass, celluloid relies on light being shone through it to make its pictures known. ‘Look!’ the upstairs photographs commanded. So, you look at this rectangle and feel something approaching meditation, or at least introspection, as you consider the Technicolor surge in front of you. Give up trying to read the words or piece together the fragmented images and the totality seems to billow with light. Sublime.

'Christian Marclay' runs at White Cube Mason’s Yard, London, until 15 May 2019.

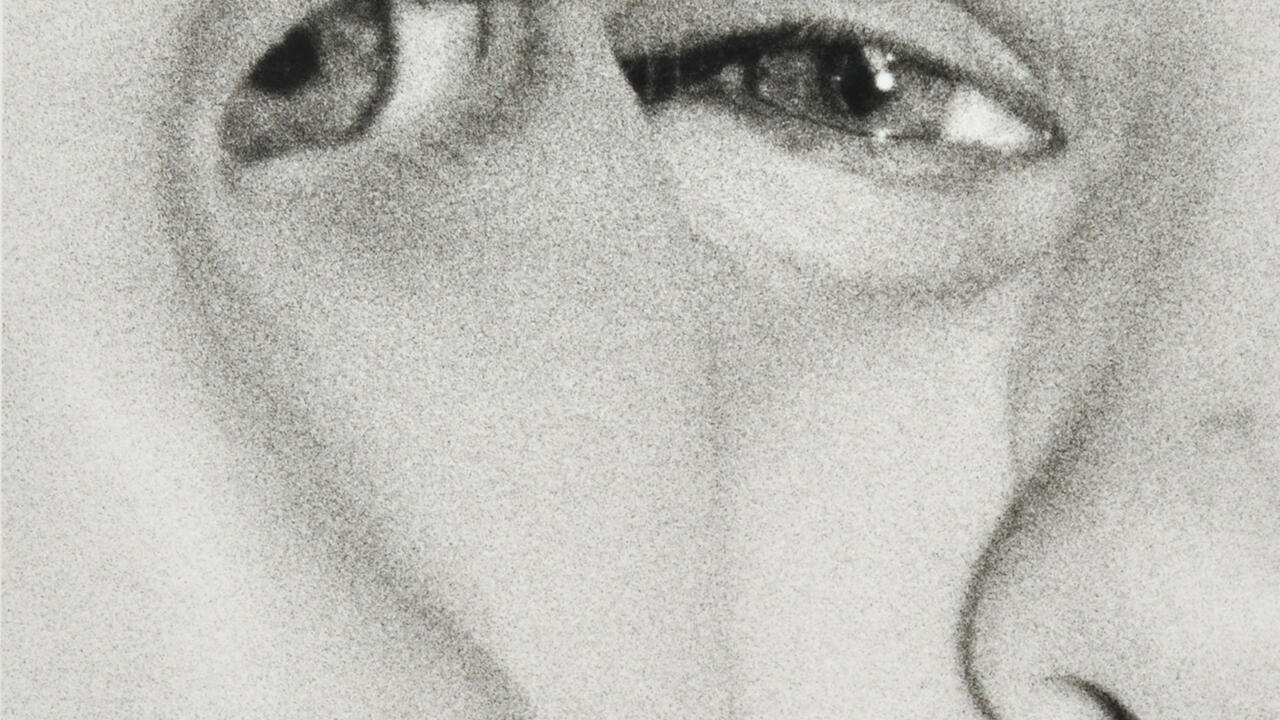

Main image: Christian Marclay, Look, 2016-2019, video still. Courtesy: the artist and White Cube, London