Collaboration: A Potential History of Photography

Critiquing the dominance of the white imperial gaze at Ryerson Image Centre, Toronto

Critiquing the dominance of the white imperial gaze at Ryerson Image Centre, Toronto

In ‘Collaboration: A Potential History of Photography’, 96 photographic projects exploring alternate production models are presented through images and texts on white squares organized into eight large grids, each representing different modes and degrees of collaboration between photographer and subject. These range from the coercive, exemplified by Marc Garanger’s ID photographs from the 1960s of unveiled Muslim women during Algeria’s French occupation, to the democratic, such as W.E.B. Du Bois’s collection of photographs of African Americans, which was displayed in the 1900 Paris Exposition.

Echoing the impassioned tone of earlier avant-garde movements, the manifesto accompanying this ‘collaborative laboratory’ promotes alternate approaches to photographic production and history. It critiques a canon populated by white males whose imperial gaze asserts technical and aesthetic mastery over available subjects – a kind of visual resource extraction. In opposition, it asserts that photography – in its reliance on external systems and subjects – is ontologically collaborative. This exhibition values photography more as an ‘event’ than a product.

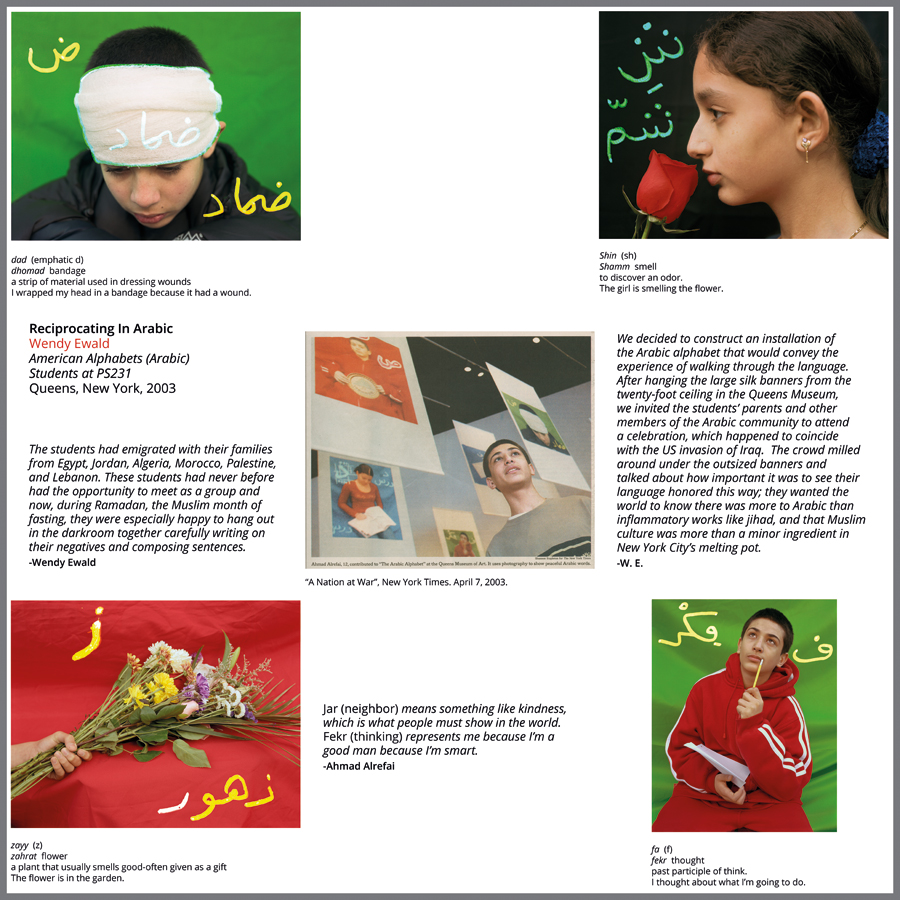

These ideas aren’t new. Since the 1970s photographers have sought strategies to disperse authorship. Projects by two ground-breaking ‘social practice’ photographers (and ‘Collaboration’ co-curators, along with Ariella Azoulay, Leigh Raiford and Laura Wexler) are included here: Wendy Ewald, who gave cameras to communities to help them represent themselves for ‘Portraits and Dreams’ (1976–ongoing); and Susan Meiselas, whose non-sensationalistic photographs document the Nicaraguan resistance (1978–79) and the collectively sourced diasporic web archive, aka Kurdistan (1998–ongoing). Adam Broomberg and Oliver Chanarin’s photographs of incarceration victims, Ghetto (2003), demonstrate an uneasy tension between collaborative intentions and exploitation. Despite their control of the shutter release, how much agency did the hospital-gowned residents of a Cuban psychiatric institution really have?

To expand on the theme of ‘Collaborations’, Ryerson Image Centre’s director, Paul Roth, along with co-curator Ilana Shamoon, has organized the most comprehensive exhibition of Jim Goldberg’s ‘Rich and Poor’ project (1977–85), which is presented in a dedicated gallery. The 47 black and white portraits of members of each economic class in the US, accompanied by archival materials, arose from Goldberg’s awareness of increasing economic division as postwar decline exposed the contradictions of American exceptionalism. Moving to San Francisco, he began visiting the struggling poor in crumbling welfare hotels and the sheltered elite in elegant homes.

After photographing his subjects, Goldberg returned with prints and lists of questions: ‘How do you look in the photo?’ ‘What’s it like being poor/rich?’ In an audio recording of his interview with the leisured Mrs Stone and her servant, Vicky Figueroa, he roots out the painful experiences and self-delusions that often accompany sharp inequality. In the final image, Vicky stands stiffly behind her employer. Her handwritten comments beneath their portrait clarify the chasm between them: ‘My dream was to become a school teacher […] I have been a servant for 40 years.’

In another image, a man and woman stand in happy embrace on one edge of a cracked wall. Far across the frame a baby lying on a bed cries, arm outstretched to the camera. Hand-writing beneath the frame reads: ‘Me and Bobby been together for two weeks and we’re still happy.’ Perhaps Goldberg hoped that by inviting subjects to add their words to the frame, their portraits would become more objective. But more often, a multiplicity of perspectives – artist, subject and viewer – collide in sad ambiguity.

‘Collaboration’ critiques the elevation of singular artists. Goldberg’s ‘Rich and Poor’ offers a model of concerted practice. Their pairing introduces interesting tensions: separating one collaborative project into a conventional exhibition format illustrates the difficulty of realizing new display models for endeavours that aim to reposition the traditional elevation of artist, curator and critic. Old art habits die hard.

‘Collaboration. A Potential History of Photography’ runs at Ryerson Image Centre, Toronto, until 8 April.

Main image: 'Collaboration. A Potential History of Photography', 2018, installation view, Ryerson Image Centre, Toronto. Courtesy: Ryerson Image Centre, Toronto; photograph: © Clifton Li