Critic’s Guide: Berlin

Ahead of Berlin Gallery Weekend, a guide to what to see across the German capital

Ahead of Berlin Gallery Weekend, a guide to what to see across the German capital

Kasia Fudakowski

ChertLüdde

28 April – 17 June

Opening: 28 April 6–9pm

Sorry, but you won’t be able to see all of Kasia Fudakowski’s latest exhibition at ChertLüdde, ‘Double Standards: A Sexhibition’. Not all of it, anyway. Whereas the London-born, Berlin-based artist’s elongated plaster sculpture David Cameron and Boris Johnson, presented in 2016, allowed viewers to move freely from left to right and position themselves next to their lying sycophant of choice, here Fudakowski has split the Kreuzberg gallery in two, forcing visitors to choose which half they want to see. Once a decision has been made, there are no take-backs, no do-overs, but by way of a sneak preview: one room is decorated with pairs of wooden breasts, draped from metal bars like benippled castanets.

This physically enforced opposition is Fudakowski’s tongue-in-cheek response to the 21st-century’s drooling infatuation with polarization, whether in the hotly contested battlegrounds of gender, politics, or further afield. Such binaries lead discourse to stagnate, something that Fudakowski illustrates at ChertLüdde with her imposed echo chambers. We are forced to pick a side, mingle with our peers and, in doing so, realize how little we’re actually seeing. As the title ‘Double Standards’ suggests: we all want to sermonize, to argue our case, but God, not with them.

Helga Paris

Between Bridges

27 April – 17 June

Opening: 26 April 6–9pm

In the early 1980s, at a meeting of artists and photographers convened in East Berlin, Arno Fischer proposed that the assembled group systematically divide and document the GDR, just as the US government had done in the 1930s and ’40s. Helga Paris, a self-taught photographer who was born in Gollnow in 1938 but moved to Prenzlauer Berg in 1966, took Halle in Saxony-Anhalt, where her daughter was based at the time. The reams of photographs produced during this period are characteristic of Paris’s work: intimate snapshots that capture and chronicle the quotidian aspects of daily life in postwar East Germany. A pigeon takes flight against a derelict backdrop; commuters tentatively cross roads reduced to dirt; a trio of children pose as if adult, hands behind backs, hands on hips.

At Wolfgang Tillmans’s project space Between Bridges, Paris presents ‘Berlin’, a collection of touching, personal portraits depicting friends, family members and neighbours, positioned within their shared, collective environment. These images operate within two distinct timezones, recalling a Germany that has now become a memory, while paying homage to a sense of community that remains as tangible as ever.

Eva Kot'átková

Meyer Riegger

28 April – 24 June

Opening: 28 April 6–9pm

Eva Kot´átková has a long-standing interest in the human body as an unwitting receptacle for various forms of physical and mental conditioning. Over the years, she has presented oversized sets of clamps and measuring devices; domineering ‘re-education’ machines; and hulking metal cages meant to house (or imprison) heads, arms, entire bodies. This is dark stuff, steeped to breaking point in historical reference, but thankfully there is more to the work than simple old-school sadism. In visualizing how easily correctional instruments can come to resemble torturers’ playthings, Kot´átková attempts to provoke a collective breaking away from the shackles; to lift the title of a 2016 collage: an unlearning of the body.

For her latest exhibition at Meyer Riegger, Kot'átková turns inwards, quite literally, finding within the fictionalized day-to-day workings of a stomach a metaphor for the life of a depressive, a recluse, an introvert – someone who struggles to deal with it all. From Kot'átková’s ‘The Diary of a Stomach’, which lends the show its title:

Tuesday afternoon

I’m waiting. So far empty. It’s not pleasant working on empty. Even worse is the feeling of loneliness. Darkness and silence.

Candice Breitz

KOW

April 29 – 30 July

Opening: 28 April 6–9pm

There is a particular strain of charity advert in which a celebrity, invariably positioned in front of a green-screen, is enlisted to make a story of suffering slightly more attractive. Ordinarily, it’s Alec Baldwin; sometimes it’s Julianne Moore. For her latest show at KOW, South African artist Candice Breitz plays upon this cliché, enlisting, well, Alec Baldwin and Julianne Moore (and a green-screen). Titled ‘Love Story’, the exhibition takes its lead from interviews that Breitz carried out with six refugees, each of whom told their own story of oppression and displacement. José Maria João, for instance, was a child soldier in Angola; Luis Ernesto Nava Molero, a political dissident in Venezuela. In the first room of KOW, renditions of these stories, performed to camera by six actors (Baldwin and Moore included), are woven together into a montage of faux suffering. In the second, we meet the individuals themselves, who recount the experiences first hand. Via this juxtaposition, Breitz leads us to question not only the media’s airbrushed depiction of trauma, but also the ways in which we have allowed ourselves to become influenced by it.

Dara Friedman

Supportico Lopez

28 April – 14 June

Opening: 28 April 6–9pm

The ‘non-verbal voice’ was of particular fascination to the experimental theatre director and voice coach Jerzy Grotowski, born in Rzeszów, Poland, in 1933, and who died in Tuscany in 1999. Grotowski’s proposition was that to truly (truthfully) project, one should draw the voice out of the whole body – speaking not just from one’s throat but rather from oneself. For her latest film, Dichter (Poet, 2017), presented for the first time at Supportico Lopez, Dara Friedman plays with this technique, instructing a troupe of 16 actors to each read a poem that is particularly meaningful to them, but to read it with Grotowski’s philosophy of bodily delivery in mind (the 16-strong cast are captured, perhaps not coincidentally, on 16mm film). As with Friedman’s joyous film Dancer (2011), which saw her trail numerous figures from a distance as they danced through Los Angeles, somehow becoming part of the city in the process, here her orators seem to extend beyond their bodies. They look straight to camera. They crawl. They bend, snarl, jump, and they strip, not simply articulating their feelings, but rather embodying them – or allowing themselves to be embodied.

Lukas Quietzsch

Schiefe Zähne

21 April – 21 May

There are many layers (metaphorical, literal) to Lukas Quietzsch’s ‘Makel und Schimpf’, the inaugural show at Prenzlauer Berg's newest gallery, Schiefe Zähne. One of the six paintings on display, each of which is characterized by muted, washed tones of fluorescent orange, features a rough assemblage of road signs, frantically warning against something out of sight. Beneath is the rinsed out memory of something less regimented: trees, maybe, in the shade of which children might be playing. In a less agitated work we find an old barn house, structure untouched bar a faintly outlined parade of ducks that march affront its bottom floor; in another, an L.S. Lowry-esque tableau obscures a much murkier scene – or is obscured by it. The title of the exhibition gives us an idea of what Quietzsch is aiming for here. Loosely translated, a Makel is a stain or blemish that ruins something beautiful, while a Schimpf is what ordinarily ensues: an impassioned rant. (The press release provides an all too recognizable example of this, telling the story of a relationship marred by a flat-mate’s inability to do the washing up.) With his murky palimpsests, Quietzsch illustrates how easily our appreciation of a particular scene can become corrupted. But, stretching this, he touches upon the very ambiguities of perception. Quietzsch displays his die Makel, his deficiencies, as finished products, thus questioning whether they are die Makel at all. And isn’t this true of everyday life? What might be an imperfection to some goes completely unnoticed by others. Or maybe I’m wrong: it’s all about perspective.

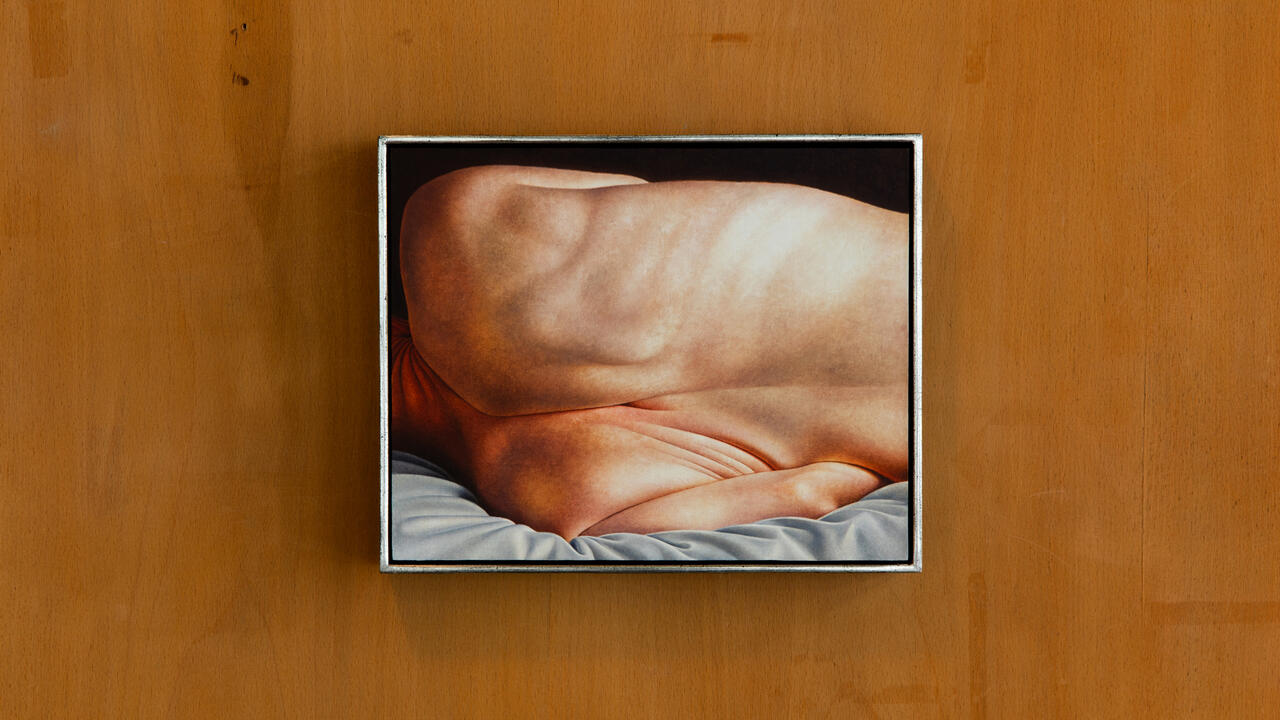

Olaf Metzel

Wentrup

29 April – 17 June

Opening: 28 April 6–9pm

In 1987, the installation of a tower of crowd control barriers stacked in Berlin's Kurfürstendamm resulted in large-scale protests. The work, Olaf Metzel’s 13.4.1981, was a response to a violent riot that had taken place on the same site six years prior, when it was falsely reported that a Red Army Faction terrorist had died in prison following a hunger strike. In spite of the six years that had elapsed, Metzel was painted as terrorist sympathiser and left the capital for Munich. The work was dismantled the following year.

Metzel has made heavily politicized work ever since, defiant in his continued attempts to highlight the gloomier aspects of society. For his second exhibition at Wentrup, he takes to task the false visions of utopia that are peddled through the building blocks of Western postwar architecture. Titled ‘Platte’, or ‘pre-fab’, the show sees numerous iconic examples of social architecture (Antti Lovag’s Palais Bulles, 2016; Renzo Piano’s Whitney, 2016) printed onto aluminium and then crushed into large-scale scrap-sculptures. This act of structural destruction can be taken as both a comment on the way in which the state’s attempts to control the populous by design often fail (see the various examples of Brutalist architecture that now stand as emblems of urban decay), and a metaphor for how that very populous might rise up and protest against such attempts at mass-management: hold them up and squeeze them until they break.

Elsewhere, Esther Schipper inaugurates its new space at Potsdamer Strasse 81E with a joint presentation of Angela Bulloch and Anri Sala; Kraupa-Tuskany Zeidler becomes the temporary home for Guan Xiao’s ‘Living Sci-Fi’; Mehdi Chouakri also opens its new gallery space in West Berlin with a solo exhibition of Charlotte Posenenske; Kewenig present the work of South Korean artist Kimsooja; and Galerie Neu presents two shows by Andreas Slominski and Cosima von Bonin at Linienstrasse 119abc and Mehringdamm 72 respectively.

At the city’s institutions: Museum Berggruen presents George Condo’s ‘Confrontation’; KW-Institute has three solo shows on view: Ian Wilson, Adam Pendleton, and Paul Elliman; Martin-Gropius-Bau welcomes Juergen Teller’s ‘Enjoy Your Life!’; Adrian Piper occupies the main hall of Hamburger Bahnhof; Deutsche Bank KunstHalle presents a broad range of work by Kemang Wa Lehulere; and in the rotunda of Schinkel Pavilion is a small collection of drawings and sculptures from Pierre Klossowski.

For more current shows in Berlin visit On View.

The full list of galleries participating in Berlin Gallery Weekend 2017 can be found here.

Main image: Olaf Metzel, Lúcio Costa (1) (detail), 2016, aluminium, stainless steel, digital print, red marble, 150 x 105 x 70 cm. Courtesy: the artist and Wentrup, Berlin