Critic’s Guide: Cologne

Ahead of the 52nd edition of Art Cologne, your guide to the best shows to see in the city

Ahead of the 52nd edition of Art Cologne, your guide to the best shows to see in the city

Ana Jotta

Temporary Gallery

22 April – 29 July

To grasp Ana Jotta’s work is to hold water in your hands. Momentarily, it remains, pooled and perceptible, only to seep through the cracks in your fingers and depart once and forever. Fleets of decorative projection screens morph into Philip Guston facscimiles; becoming embracing cartoons which give way to clusters of candles, curled as if huddling for warmth. Jotta’s work is a continuous extrapolation of a life – illustrated by her 2014 book Footnotes – which collects and displays the manifold objects and paraphernalia that the Portuguese artist has collected over the years. These forms are not assembled to satisfy a nostalgic impulse – the majority are discarded once documented – but are instead incorporated into a personal map that is continuous, ever-changing, always-curious.

The heartbeat of Jotta’s exhibition at Temporary Gallery is fala-só, a 40-metre roll of blue fabric worked on by the artist between 2014 and 2017. It repeats, over and over again, the outline of a single glazier who she recalls from her childhood in Lisbon. The tapestry is a working through of an idea, a wandering through of a memory; not the output of an artist attempting to resolve or reconcile, but simply entertain, over and over again. Accordingly, fala-só is an outdated Portuguese term meaning ‘soliloquy’.

Catharine Czudej

Ginerva Gambino

14 April – 9 June

In the text accompanying Catharine Czudej’s exhibition ‘Not books’, we meet John Barioni. John is a Californian with a goatee and an immovable trucker cap. John likes playing pool. He has a table in his basement; he runs a company called Barioni Cues. John is also a prolific YouTuber, who you might recognize from such hits as ‘OB SHAFT DISSECTION- STEP BY STEP’ (31,831 views) and ‘HOW TO MAKE A POOL TABLE BALL POLISHER’ (258,708). In this regard, the text notes, John is ‘the prototypical DIY-guy on YouTube’. For the lowest prices, he offers, to quote his website: ‘the highest quality products with out standing [sic] performance.’

DIY is the kernel of Czudej’s exhibition, or rather: the manner in which ‘making home’ is predominantly seen as a masculine operation, while ‘home-making’ is more readily viewed as a feminine activity. The former comes with tools, toil and an expectation of economic reward; the latter is bound up with ideas of consumption, motherhood and care. The press release quotes from Juliana Mansvelt’s Geographies of Consumption (2005): ‘male control of the physical environment’, expressed via exertions of pre-industrial labour, conjures a false impression of male dominance. In ‘Not books’, a show comprising, amongst other things, paintings, sculptures and modified mouse-traps, Czudej reclaims this right to ‘do it yourself’ as a genderless realm. One where you can make, if so inclined, a collection of home-made ball polishers. (Czudej has done just that.)

Haegue Yang

Museum Ludwig

18 April – 12 August

‘Historical narratives overlap with personal ones in the most unlikely of ways.’ These words belong to Haegue Yang, whose recent ‘Influences’ piece for frieze ebbed through the various bygone tales that inform her multivalent practice, from the musical compositions of Isang Yun to the families who were left estranged following the Korean oil crisis of 1971. In Yang’s work, such stories breathe through ovoid assemblages of bells mounted on wheels, towering installations of Venetian blinds and dense tufts of artificial straw – woven, plaited and draped. These are structures that, like their narrative forebears, are settled but forever in flux; stable but retaining the ability to move – or be moved by another. Thus, when Yang writes of the effects of Korea’s fractious history upon its infrastructure, she could be talking of her own practice: ‘regions are unexpectedly connected yet remain disconnected’. In these sculptures, divergent tales are momentarily reunited, all the while refusing the temptation to declare themselves fused. This abstraction of the actual should not be misconstrued as a yearning for the closure, but rather a running ‘leap into a dimension that cannot otherwise be understood’. It is one that, as is hinted at by the title of Yang’s vast survey at Museum Ludwig, ‘ETA 1994 – 2018’, will always be travelling, but will never touch down.

Alex Da Corte

Kölnischer Kunstverein

20 April – 17 June

Alex Da Corte’s installations are what your parents imagine acid might be. Rooms are plunged into deep purple hues; vibrant neon crowns glare from smoky enclaves. Adidas Superstar trainers sit deconstructed, unlaced and five-feet tall; a vast, wailing baby floats above an art fair (its title: Free Money, 2016). For his exhibition at Kölnischer Kunstverein, ‘THE SUPƎRMAN’, Da Corte revives a many-faced character from his 2017 show at Josh Lilley, London: Eminem (a.k.a. Slim Shady; a.k.a. Marshall Mathers; a.k.a. B-Rabbit; a.k.a. a rapper who, we can all agree, should have called it a day in 2004). In the institution’s central hall, Da Corte will erect a large-scale stage on which to examine, via imitation, four iterations of the Detroit-born star – as pop-cultural icon; as social phenomenon; as a brand so sensationally vast that in 2017 the word ‘stan’ was added to the Oxford English Dictionary, its definition, in accordance with Eminem’s song of the same name: ‘an overzealous or obsessive fan of a particular celebrity’. Through this act, this invocation, this embodiment, which at Josh Lilley played out across three dystopian videos, Da Corte wants to assess another wild act of imitation: ‘[I want] to understand the character that he portrayed, the Slim Shady character, and try to understand and empathize with who that heteronormative, middle class white male is.’

Tobias Spichtig

Jan Kaps

17 April – 26 May

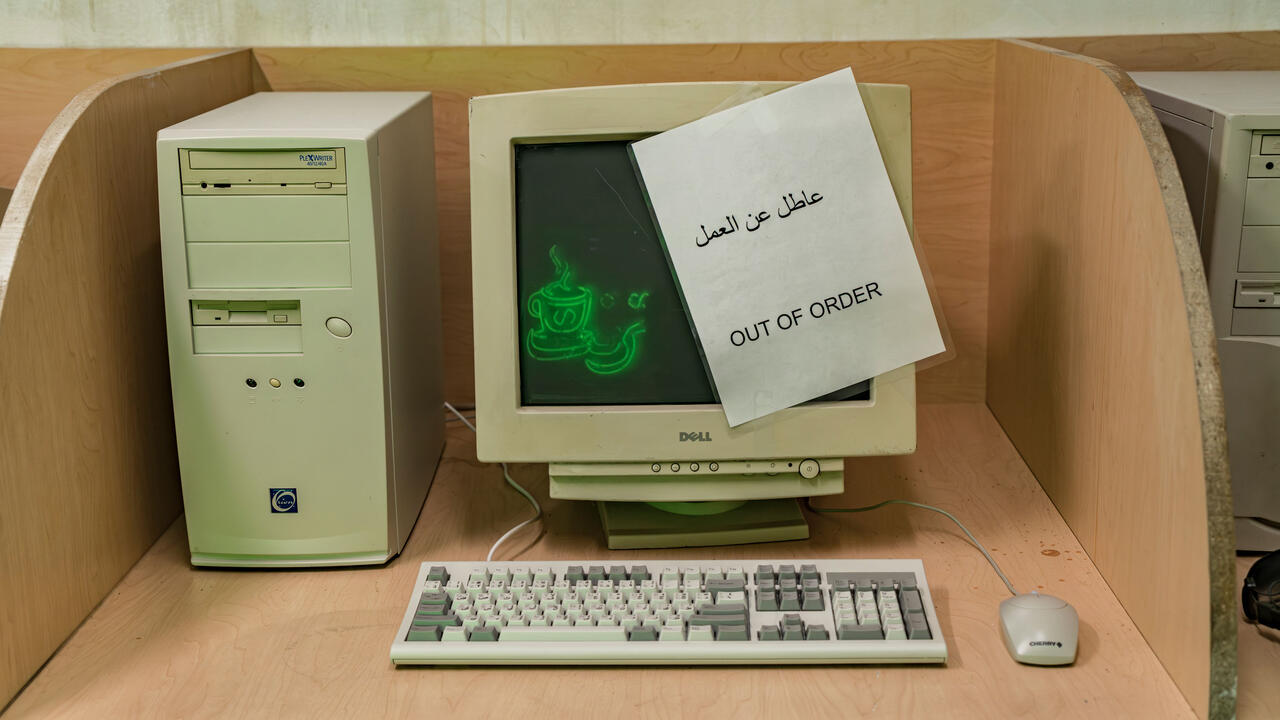

Tobias Spichtig makes visible what it is to be left behind. Rooms are crowded with unwanted fridges; sticky, glazed garments stand erect and bereft of host bodies; mattresses stretch from walls to confronting walls, their sheets grime-clad and sullied from use. These are, perhaps, the memories that we cannot help but have, but can never come to cherish; the rusty, long-since discarded stage-sets within which we have rehearsed, refined and, ultimately, performed the narratives that we actually hold dear. A 2016 sculpture takes the title LET IT ALONE, THOU FOOL; IT IS BUT TRASH. In Spichtig’s work, this exorcism can never take place. ‘Long Stories’, the Swiss artist’s latest exhibition at Jan Kaps, comes accompanied by a fictional tale, written by Theresa Patzschke, which speaks of love, loss and mundanity, and the seemingly innocuous decisions that lead us to each. The final line reads: ‘You walk into the dark forest with small, deep blue flowers.’ There, the sweet, sensuous details that enrich our happiest memories. In an accompanying image, we find the trodden crud that we can’t seem to shake: an exhausted sofa, its pillows muddy brown and unmanned.

Andreas Maus

Rob Tufnell

5 April – 28 April

We have a tendency to believe that things change – an unfortunate byproduct of our desperate craving for ‘progression’ and ‘meaning’. It is, of course, a naïve impulse: flatten time, flatten context, and you will find that little but homogeny remains – of violence, vibrancy, faith and all the raw banality that mopes between. Andreas Maus carries out such a levelling. His drawings tempt in a wide range of settings and scenarios: a bulbous Kaiser Wilhelm II berates at the outbreak of World War I; a circus trainer is mauled by a big cat; an AfD henchman sees a chainsaw rip through his crown; Donald Trump flees an expiating wall of flames. But thanks to a uniting medium (biro), colour scheme (red, blue, black, green) and technique (near-obsessive circular marks), these disparate scenes appear as consecutive stills from the same narrative strip. Maus visually flattens the contexts and time-frames and, in doing so, illustrates how the various small tragedies of our current era are little but repetitions of those which have come before. Approached from one angle, the reading is bleak; terrors are frequent, in spite of them frequently being declared dead. Approached from another, the outlook is brighter: the many maladies of the contemporary ages can, ultimately, be felled, as they have been so many times before.

The Night Climbers of Cambridge

Delmes & Zander

17 April – 31 May

In 1937, an author working under the ludicrous mononym ‘Whipplesnaith’ published The Night Climbers of Cambridge with Chatto & Windus, a photobook documenting the nocturnal exploits of Cambridge university students. In a series of gritty, monochrome plates, a set of which will be on view at Delmes & Zander during Art Cologne, groups of young, white, probably wealthy (almost definitely drunk) men vault over buttresses, shimmy between drainpipes, stand proudly atop distant nave roofs. On the risk involved in such daring acts of institutional critique, dear ‘Whipplesnaith’ (real name, hilariously: Noël Howard Symington) was defiant: ‘If you slip, you will still have three seconds to live.’

As images, and images alone, the series is equal parts beautiful and entertaining: photographs of human feats will always be engaging, as will visual evidence of those able to exploit the gaps between imposed sanctions (physical or otherwise). But there is something tragically funny about the project as a whole. Here, in the 1930s, shortly after the Great Depression buckled Britain’s industry and plunged the nation into a suffocating period of mass unemployment, we have the cream of the privileged class flexing their rebellious muscles in the most ludicrous of ways; asserting their right to civil disobedience from the roof of St John’s College Chapel and then anonymously publishing their acts of sin for fear of academic retribution. Give ’em hell, kids …

For more shows to see in Cologne head over to On View.

Main image: Haegue Yang, Knotty Spell in Windy Acoustical Gradation (detail), 2017, mixed media, 195 x 88 x 88 cm. Courtesy: Galerie Barbara Wien, Berlin © Haegue Yang, photograph: Ketty Bertossi