Critic’s Guide: London

A guide to the best of the summer shows

A guide to the best of the summer shows

Arthur Jafa

Serpentine Sackler Gallery

8 June – 10 September, 2017

Walking into the Serpentine Sackler Gallery, the viewer is handed a set of wireless headphones, which can be adjusted to listen to the three video installations in the space (Mix 1_constantly evolving, Mix 2, etc., all 2017). Each is a different mix of moving images, which include samples including a video directed by Kahlil Joseph, a personal account by a man who at the last minute decided not to run the 2013 Boston Marathon that was subject to a bomb attack (‘all my friends were injured’), and parts of a documentary about a poverty-stricken African-American community in Venice, California. Alongside these are a collection of the picture books Jafa has been assembling and arranging in collages since 1990, comprising imagery of black life and culture. There are also a few portraits Jafa took via FaceTime and archival photographs blown up to form wallpaper, as well as works by photographer Ming Smith, photos from artist Frida Orupabo’s Instagram feed, and videos from a YouTube channel by user ‘Mussylanius’. For anyone who has seen Jafa’s masterful seven-minute video collage Love is the Message, the Message is Death (2016) – shown last year at Gavin Brown’s enterprise in New York and more recently at MOCA, LA – the Serpentine exhibition shows a process leading to that succinct work: in the three videos, as in the picture books, the same cut-and-paste technique allows considerations of the representation of black aesthetics to be expanded and complicated via this process. This exhibition, titled ‘A Series of Utterly Improbable, Yet Extraordinary Renditions,’ functions both as an introduction to Jafa’s working method as well as a mirror to his complex, nuanced view of American society today.

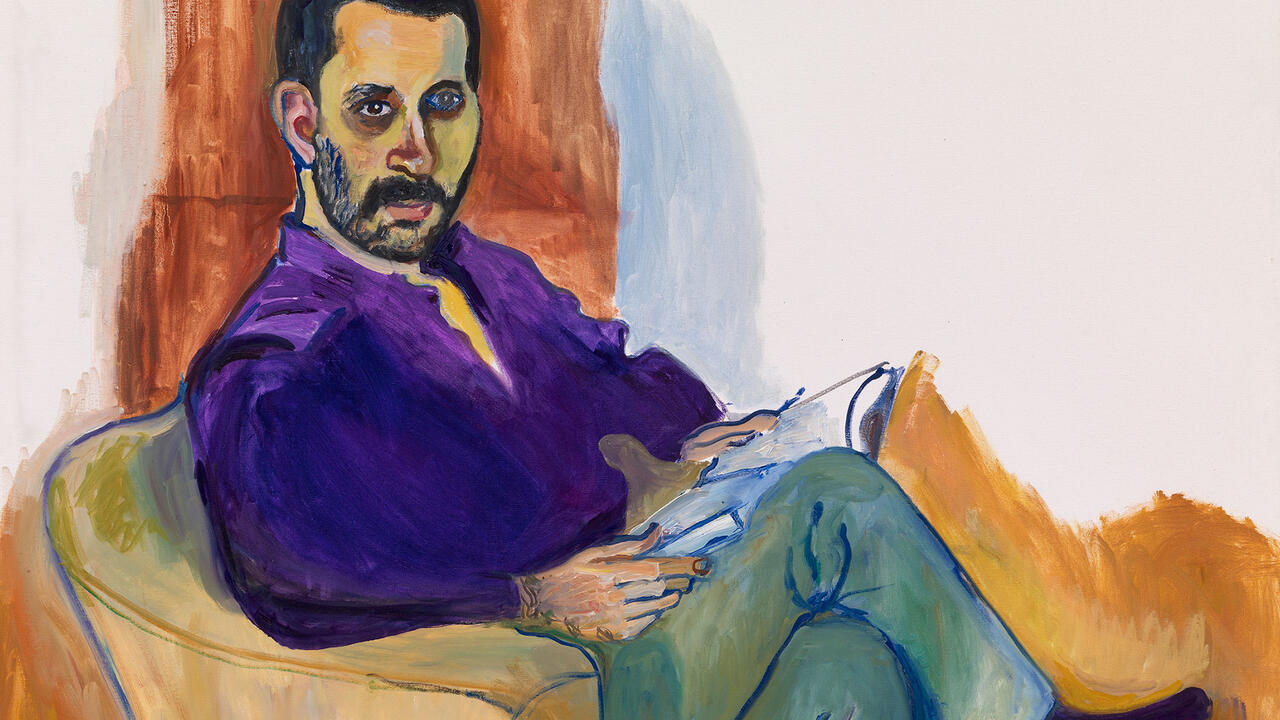

Alice Neel

Victoria Miro

18 May – 29 July, 2017

Alice Neel’s recognizable portrait style, with the canvas left raw at places and the subject painted frontally, often seated on a chair in a nondescript interior, is here a wonderwork of intimacy. The painter, who died in 1984, spent most of her years living in Harlem, and this exhibition, aptly titled ‘Uptown,’ curated by writer Hilton Als, celebrates the diversity of neighbourhoods in Uptown New York – Neel moved from East Harlem to Morningside Heights in the 1960s – as well as of the people who populated Neel’s life. Though never a society portraitist (some of her most famous works are portraits of fellow artists such as poet Frank O’Hara), it’s surprising to see the people who surrounded Neel in her daily life: the black son of the superintendent in Neel’s building, a Chinese-American medical school associate of Neel’s son, a taxi driver she knew who identified as a Black Muslim nationalist and sat for her wearing a kufi and a trench coat. With an eye to art history, the exhibition underlines a part of Neel’s practice rarely explored and tells a story of how to be an artist in a big city, and how to be a neighbour, too.

Tamara Henderson

Rodeo

17 May – 29 July, 2017

‘Seasons End: Panting Healer,’ is the third instalment of a project initiated for Glasgow International in 2016 and expanded at REDCAT, in Los Angeles (it heads next to Toronto’s Oakville Galleries). With each iteration, ‘Seasons End’ has morphed and changed. Using materials Henderson collected through her travels, the artist presents works that in themselves embody the passage of time – the four paintings on view refer to the four seasons and the 25 handmade textile pieces on handmade mannequin-like sculptures reflect the hours of the day (plus one more for someone who apparently fell ill during the Los Angeles presentation). Yet a complex narrative she had written plays out in the works and the text accompanying it. The result changes the gallery completely, with gauzy curtains hung against the windows and soft coloured lights replacing the neon. It’s sentimental work that relates to the physical world around us and the way it affects our constitution, but also builds its own mythology, which will be reenacted at a performance at the Serpentine Galleries Park Nights series in Hyde Park on 21 July, where the handmade costumes will be activated, allowing for a sense of change and atmosphere to be physically embodied.

Megan Plunkett

Emalin

24 June – 29 July, 2017

‘I Live by the River’ (2017) is a series of photographic prints. #21 is a silver gelatin print, whereas the other 14 are digital versions derived from the original photograph. All show the image of plaster casts made of a broken Toyota car bumper, where the brand name is still visible. Yet they’re not meant to be discussed for thematics, but rather, seen for their materiality: a dark-room or gallery-oriented interest in photography and its presentation, where small differences in print, frame, and grouping create a sense of difference that is stranger, more haunting than it would be if the photos were dissimilar. These works are not a document of anything really, rather an exercise in repetition. The title of the show – the Los Angeles-based artist’s first in London – ‘I Bet You Wish You Did and I know I do,’ like the photos, feels between the lines: a cheeky address to the viewer to try, and fail, then try again to build a coherent, easy system of meaning around this challenging exhibition.

‘The Place is Here’

South London Gallery

22 June – 10 September, 2017

A travelling exhibition that had its origins in a small presentation at the Van Abbemuseum in Eindhoven, curated by Nick Aikens, expanded for a much larger one at Nottingham Contemporary, curated by Aikens and Sam Thorne, and currently split between the South London Gallery and Middlesbrough Institute of Modern Art, the title of the Van Abbemuseum iteration was ‘Thinking Back: a montage of Black Art in Britain.’ In South London, nothing about this exhibition, including the archival matter, feels remotely nostalgic. Dedicated to black art in the UK in the 1980s, the works put forth different positions about race, gender, and socioeconomics as they intersect with issues such as migration, race relations in the United States, workers’ rights and hate crimes. Archival material from the Brixton Art Gallery and the Black Art Gallery, show the challenges and successes of exhibitions and projects organized to promote the work of black artists and other artists of colour. It’s a history of institution-building and awareness raising. Artists such as Mona Hatoum and Isaac Julien show early works that feel more personal and raw than much of their later. (The series from which Julien’s photos were taken, ‘Looking for Langston’ [1989], is also currently on view at Victoria Miro.) ‘The Place is Here’ runs in conjunction with ‘Soul of a Nation,’ the Tate exhibition focused on black art in the United States after the Civil Rights Movement. Thinking on them together raises a strong sense of the relevance of these histories in our troubled, divided times.

Monira Al Qadiri

Gasworks

13 July – 10 September, 2017

Not much prepares a viewer to be transported into an American diner in a South London non-profit. It gets even more surprising when, sitting on the vinyl benches and leaning elbows on Formica tables complete with salt and pepper shakers and plastic ketchup and mustard bottles, that same viewer sees in a video the same diner on an alien spaceship. In the short film the artist narrates how as a young girl growing up in Senegal (her father was a Kuwaiti dilpomat) she believed the world to be infiltrated by aliens: ‘where embassy buildings were actually extra-terrestrial spaceships and landing pods.’ Back in Kuwait, the context of the First Gulf War only strengthened the belief: those flashing lights in the sky? Spaceships. The soldiers? Aliens. The tale climaxes in the spaceship diner into which Al Qadiri's sister follows her mother and sees aliens casually conversing with humans, ‘as though they had developed long relationships over time’. In the other gallery – brace yourself for more Americana – is a floating burger, roating above a plinth, the only lit object in a darkened room, accompanied by a soundpiece discussing the futuristic architecture of the Gulf. If the idea of America is fading away, passing with the 20th century that gave it rise, it wasn’t replaced by the masterplanning of the glistening new Gulf cities. Al Qadiri’s show is a personal account familiar through its TV-channelled cultural references, but is also just weird or misplaced enough to make the viewer slightly uncomfortable, and thus susceptible to careful listening. If you listen, you hear an artist embarking from the now seemingly well-trodden paths of Gulf Futurism to a mix of 1980s sci-fi and cartoon-filled childhood memories – sharing something genuine, a little sad, quite funny, and markedly universal.

Gabriel Kuri

Sadie Coles HQ

23 June – 19 August, 2017

At first look Kuri’s works always seem to tease, asking if you’re in on the joke; that being the almost oblique, inaccessible, or invisible principles that must govern the works. In fact, the plastic eggs on a plinth (box for sort, all works 2017), Plexiglas-and-rock floor sculptures (adjustable point made; standing points made), and monochrome black vacuum-formed panels (Quick count 1, 2, and 3) all expose a very human interest in utility. This exhibition has a slick look, with objects and plinths made of stainless steel, then combined with cement, rocks, and felt — there’s also some mussels for the inescapable reference to Marcel Broodthaers – forming sculptures and wall works that constantly tread the line between the sheen of industrial aesthetics and the handmade. Surprising juxtapositions feature too, with moss and drinking straws embedded into slick metal plinths. One can either grasp at the identifiable, easy-to-chart aspects (here a ‘mussels’, there a ‘painting’) to reverse-engineer the artist’s organizing principles, or just allow familiar things to become foreign, and wonder on that.

Main image: Monira Al Qadiri, ‘The Craft’, 2017, installation view, Gasworks, London. Co-commissioned by Gasworks and the Sursock Museum. Courtesy: the artist; photograph: Andy Keate