Cy Twombly

MUMOK, Vienna, Austria

MUMOK, Vienna, Austria

Bringing together work from every period – collages, pencil and crayon drawings, black and white and intensely coloured paintings, bricolage sculptures and early and recent photos – one might expect that this retrospective would confront the myriad interpretations hovering over Twombly’s diverse output. Yet it doesn’t. Works are arranged mostly chronologically, and flit between emphases on form and content, text and image. The photographs, woven amongst the paintings in the exhibition, raise obvious questions – how does Twombly’s photographic practice fit in with the rest of his work and why has he increasingly turned to the medium in recent years? Both questions are obliquely addressed, their answers gently insinuated, which isn’t a surprise considering Twombly’s work, which, as Jeff Wall writes in the show’s catalogue, avoids ‘any feeling of untoward effort, any intellectualizing aspect, and a reduction of any necessity for understanding the art or finding explanations for its effect.’

It may seem unlikely that Twombly’s gestural technique of drawing and painting would be transferable to photography. Yet seeing his photographs and paintings inhabit the same space, they seem like mutual extensions and translations of each other, particularly the still lifes. Taken together, they capture and sustain an overwhelming sense of pattern-evoked moods. The photos themselves, with their soft, out-of-focus and over-exposed blurriness, inevitably draw viewers nearer in order to make out their subject matter. By revealing the processes by which his work materializes, they also draw us closer to the subconscious space of the artist’s studio.

Like the writing on his paintings, Twombly’s photographic images aren’t really committed to depicting or representing the physical objects they capture. They leave behind an abstraction, patterns reminiscent of the artist’s recurring scrawls and loops made systematic and routine. Like his bricolages of wood, nails and string, these photographs feel unpredictable, as if they, too, are the result of his happening upon the materials, or peering through the viewfinder. The outcome seems to have been timed with our first glimpse.

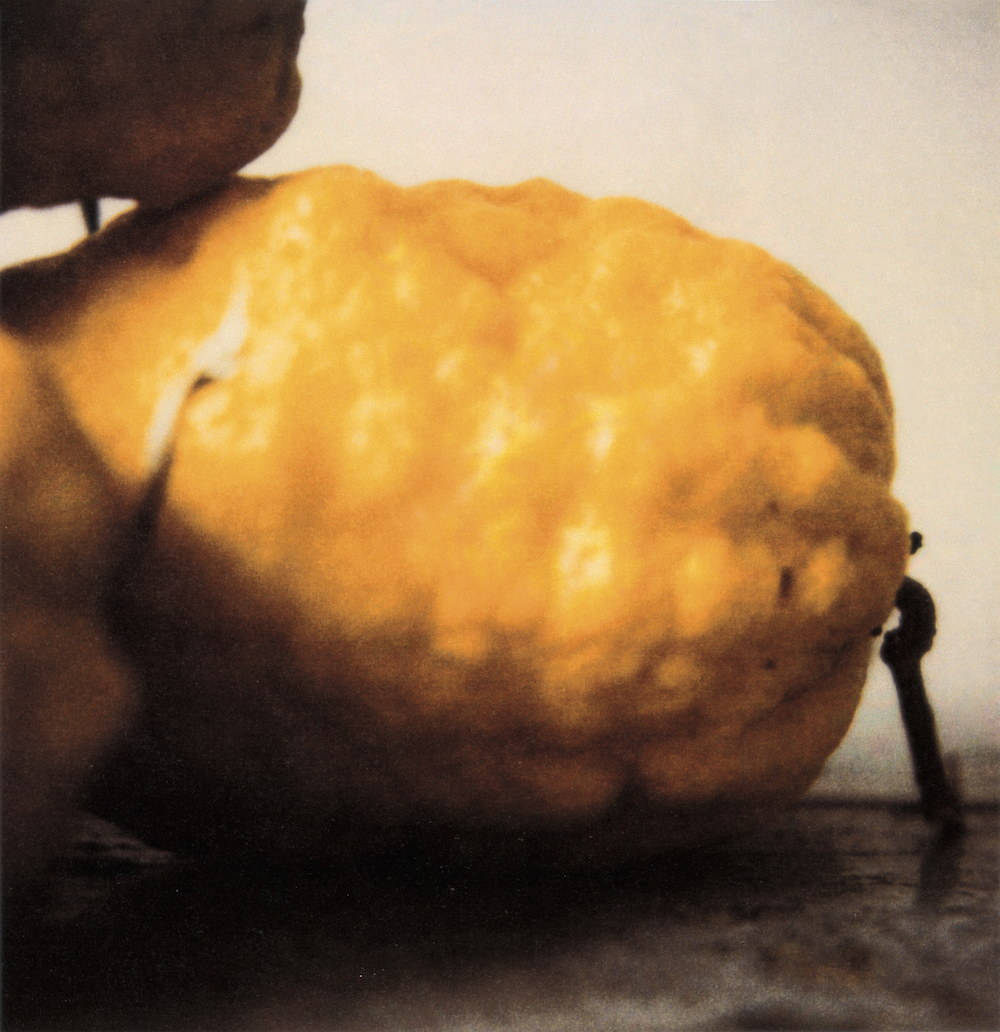

Two colour photographs of blocks of cheese (both titled Cheeses, Passo Godi, Abruzzi, 2006) are framed casually, which heightens their level of abstraction and spatial disorientation. Illuminated and shot up close, their bulbous bottoms protrude like ashen bellies. As with most of Twombly’s paintings, they almost defy comprehension until one reads the work’s title. Similarly, Twombly’s cabbages (Cabbages (bright), Gaeta, 1998) are seemingly carelessly piled atop one another, their leaves bulgy with veins, while lemons (Lemons, Gaeta, 2005) are captured close to the precipice of decay and puckered almost beyond recognition. Where his paintings derive their tension from hovering between formlessness and delicacy, his photographs contrast an abstract timelessness with the casual ease of snapshots.

But where do Twombly’s photos go where his paintings and drawings can’t? In Studio Gaeta with Bacchus Paintings (2003), we’re shown a glimpse of the artist’s works in progress in his studio. The red-streaked Bacchus paintings are shown in fragments, one behind a chair, another peeking out from the backroom, while a soft, golden light suffuses the entire scene. The shot might have been a glance Twombly threw behind him when leaving the studio, and it lends a feeling of unselfconscious immediacy. In another photograph, also called Studio Gaeta with Bacchus Paintings (2003), we see part of the same painting, shot against the wall, the red dripping down as if the painting would soon wash over the floor. Both suggest that Twombly’s work is intrinsically connected to the place and moment in which it is created – similar to his geographically-named paintings, though now the risk of allusion is neatly sidestepped.

Seeing Twombly’s paintings arranged alongside busts and baroque paintings in his studio in Interior, Rome (1985), Interior, Gaeta (2002) and Interior, Rome (2003), one senses he uses photography as a way of studying his own work from afar: on the one hand, disowning it via another medium, but on the other, letting real life and its transformative possibilities intrude. These shots of his studios and private rooms are crowded with his furniture and often framed by doorways, corridors and windows, evoking the allusions and overlappings in Twombly’s earlier collages, such as Untitled, Rome (1971), which resembled bulletin boards, to-do lists and the detritus of daily life. This sort of transformation is most palpable when Twombly captures details of works, such as a close-up of a cherub, Painting Detail, Gaeta (2000). The individual flakes on the painting’s surface become iridescent, like fish scales, and seem to be one step closer to arriving somewhere between painting and photography.