DAU’s Totalitarian Reality Show: Artwork of the Century or Stalinist Cosplay?

The multimedia art ‘experience’-cum-independent Soviet state recruited a cast of 400 to live on an enormous film set for years

The multimedia art ‘experience’-cum-independent Soviet state recruited a cast of 400 to live on an enormous film set for years

It is more than a film but not exactly an exhibition. Not quite theatre or performance, although elements of both are omnipresent. It has Mongolian shamans, Russian orthodox priests, rabbis, imams and psychoanalysts, if you need to vent. There are meticulously detailed recreations of Soviet-era apartments inhabited by people who only speak Russian. Eminent performance artist Marina Abramović is supposed to make an appearance. (She is one of the project’s many celebrity ‘ambassadors’ who also include physicists and mathematicians Carlo Rovelli and Dimitri Kaledin, theatre directors Peter Sellars and Romeo Castellucci, artists Carsten Höller and Philippe Parreno and the designer Rei Kawakubo, among others.) And, for one euro, a stony-faced barman will serve you watery coffee or a litre of beer. It is DAU, the multimedia art ‘experience’-cum-independent Soviet state that is being hailed by its creators as the art-event of the century and by the French press as a disastrous flop.

Much of DAU’s bad press is related to the rocky start of its ‘World Premiere’ in Paris, which saw its opening day pushed back due to various technical difficulties and the organiser’s failure to obtain the proper security permits from the city. Five days after its belated inauguration, half of the installation still remained closed, prompting one visitor to tweet sarcastically that ‘At DAU the immersion in the USSR is total: You wait in line for hours only to realize that nothing is there.’

The brainchild of Russian filmmaker Ilya Khrzhanovsky, DAU began in 2009 as a biopic about Lev Landau, the real-life Soviet physicist who was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1962 and whose scientific brilliance was said to be matched only by his sexual rapaciousness. To tell Landau’s story, Khrzhanovsky built an enormous film set in Kharkov, Ukraine, modelled on the site where the Soviet scientist lived and worked from the late 1930s until his death in 1968. The attention to historical detail was apparently so scrupulous that it included everything from the plumbing to the underwear worn by each of the 400 or so hand-picked participants. For almost three years, everyone lived on set, changing their clothing and hairstyles as the film’s narrative marched through the decades, and all the while the cameras rolled. More than 700 hours of film documenting this never-out-of-character lifestyle were recorded and have since been edited into 13 feature-length films, along with the original DAU biopic in the pipeline.

Since the beginning of filming to the Paris debut, the project was veiled in secrecy. Very few journalists were allowed to visit the Kharkov set, which was apparently patrolled by guards in Soviet uniform. This opacity created an atmosphere rife for rumours: as a 2011 article by Michael Idov in GQ reported, Khrzhanovsky is said to have subjected his collaborators to a tyrannical rule, encouraging them to denounce any participants they caught using anachronistic language or products. The director was even rumoured to harbour a sexual appetite of Landauian proportions and apparently dismissed female participants who refused to respond to his invasive inquisitions into their personal lives. Other journalists, including James Meek writing in the London Review of Books in 2015, emerged from DAU’s post-production headquarters in London’s Piccadilly with similarly grim stories of bizarre and uncomfortable encounters with the director and members of his staff in a room decorated with a mannequin suspended from its neck.

From now until 17 February these films can be viewed in Paris; a sort of simulacrum of the Kharkov film set is divided between the Théâtre de Châtelet, the Théâtre de la Ville and the basement of the Centre Pompidou. However, visiting DAU isn’t as simple as buying a ticket; rather, you have to apply for a visa whose ‘processing fees’ vary depending on how long you want to stay.

My own plunge into DAU begins when I am issued a visa, which is green and yellow and looks shockingly real, complete with my photograph, name and holographic watermarks (the tenuous line between reality and fiction is a theme at the heart of DAU). I have to show it to a burly security guard who verifies the personal information with my real pink and blue French visa before instructing me to leave my mobile phone in one of the hundreds of small grey locked boxes that line the walls of the concrete lobby.

One level up, there’s a three-tiered mezzanine with a dozen mirror-plated cabins on the top floor. Down a few steps is a canteen furnished with tables, chairs and lamps, all shaped like cartoonish penises. As I lean over the balcony to inspect this phallic furniture, I brush against a tall man in a dark trench coat. ‘Sorry’, I mutter and turn to apologize but the man remains motionless. A few seconds later I realize that he isn’t a man at all, but a wax figure, frozen in his leering pose. Other uncannily lifelike wax figures are scattered throughout the space, mingling and blending in with the other visitors who walk right past without acknowledging them.

When I finally sit down to watch the films, I recognize these figures as characters from the DAU universe. The man that I brushed against turns out to be a director of the institute who, in one film, pits a pair of thuggish KGB agents against some young university students who he catches smoking weed on the DAU campus. In another film, I recognize a waitress who hosts a raging bacchanal with a visiting Canadian physics professor and a gaggle of red army soldiers. Then there is Landau himself, played by the Greek conductor Teodor Currentzis. His wax mannequin, like his silver-screen counterpart, is tall and dashing with a mess of untamed dark hair. The debonair demeanour quickly vanishes, however, in a painful scene where he tries to convince Katia, the institute’s beautiful young librarian, to sleep with him by telling her to ‘let go of your fear and embrace your fantasy’. When that doesn’t work, he tries another more desperate pick-up line: ‘Show me your panties, you’ve already showed me your soul, surely you can show me your panties.’ There are many similarly uncomfortable moments in the films. For instance, one opens with a five-minute scene of scientists injecting a needle directly into the head of a live rat. In another, we witness Katia being raped by one of Laudau’s subordinates. Laudau surprises him in the act, but instead of coming to Katia’s aid, proceeds to smash her furniture in a fit of jealous rage.

Despite the grim content of these films, there is something captivating about them. The stories are slow-moving, following the characters through the banal tasks that punctuate their daily lives. The shots are also very long, with lots of camera travel between rooms and the faces of conversing individuals and very little cross-cutting. This minimal montage not only gives us ample time to appreciate the meticulousness of the costumes and scenography but also reinforces the feeling of immersion, as if we were one of the characters sitting in the physics classroom or attending one of the wild parties.

A few flights upstairs, the immersive experience continues in the apartments, which, like the downstairs mezzanine, are furnished with props from the film. Their authenticity is confirmed for me by Christian, a 52-year-old enthusiast of the USSR who has volunteered to ‘mediate’ between the visitors and the ‘participants’ who will live in these apartments for the duration of the shows. After mediating a simple conversation between me and Svetla, his Ukrainian-born wife, Christian proceeds to explain Soviet currency, the workings of Soviet appliances and the logic of the apartments’ interior design. In the adjacent apartment, four men play cards while a fifth plays an accordion. The period authenticity is less scrupulous here. One of the card players is wearing a black Nike tracksuit, another a pair of Air Jordans. A third quickly hides his iPhone in a kitschy porcelain vase as I enter the room. The others ignore my presence entirely.

Other diversions from the historical accuracy are subtler, notably the presence of works of art from the Centre Pompidou’s Russian art collection. Above a decrepit looking brown leather couch with a partial lace cover, in one apartment is Oscar Rabine’s expressionist still life Bottle and Lamp (1964); it’s hung next to Varvara (1963) by Édouard Steinberg. In another room, Sergueï’s Bougaev-Afrika’s détourned Soviet banner titled To John Cage (1999) hangs above an empty baby’s crib.

Though France’s national modern art museum has been exploring art from the former Eastern bloc for several years now, its co-sponsoring of Khrzhanovsky’s bizarre project amid the on-going Yellow Vest uprising is an ideological gesture that is difficult to decipher. There appears to be a degree of sincere nostalgia for the oblique brutality of life in the former USSR, as is palpable in the preposterous explanation that Khrzhanovsky offered to Steve Rose (in a piece for the Guardian from 26 January), for DAU’s raison d’être:

‘The system that controls us today is the cellphone. We say, “Oh great, I bought the new iPhone,” or whatever. You bought something that controls you more. What does this thing know about us? More than we know about ourselves. We live in a transparent world, but we cannot accept it.’

It is hard to take Khrzhanovsky’s thin critique of surveillance capitalism seriously, when he himself seems only too eager to be the one behind the camera, watching and controlling everything. To that end, his engagement with the historical legacy of communism has little to do with the universal emancipation of the working class or any of the other big ideas at the heart of scientific socialism at the turn of the 20th century. In fact, the French daily Libération recently published accounts of former employees of the Parisian DAU site revealing abusive working conditions, including excessive hours spent engaged in tasks meant to foster an atmosphere of suspicion and competition between workers.

For Khrzhanovsky, it all seems to be a kind of charade, a farcical costume to be worn while playing Stalin. If anything, the fact that this mammoth project is almost entirely funded by Sergueï Adoniev, a Russian telecommunications billionaire, or that, at the end of filming, real-life neo-Nazis were hired to destroy the Kharkov set before the entire site was transformed into a massive pop-up night club with a DJ set and an open bar, suggests a greater affinity with a clichéd image of contemporary art as something aloof, alienating and perniciously close to the capriciousness of a generation of bored, super wealthy oligarchs. There is no serious embrace of socialist ideas or substantive critique of contemporary capitalist society that is not undermined by the material circumstances surrounding DAU. It is a monument to totalitarianism that seems to long for the simpler times of the Cold War when, at least you knew who your enemies were.

DAU will run at Théâtre de Châtelet, the Théâtre de la Ville and Centre Pompidou, Paris until 17 February.

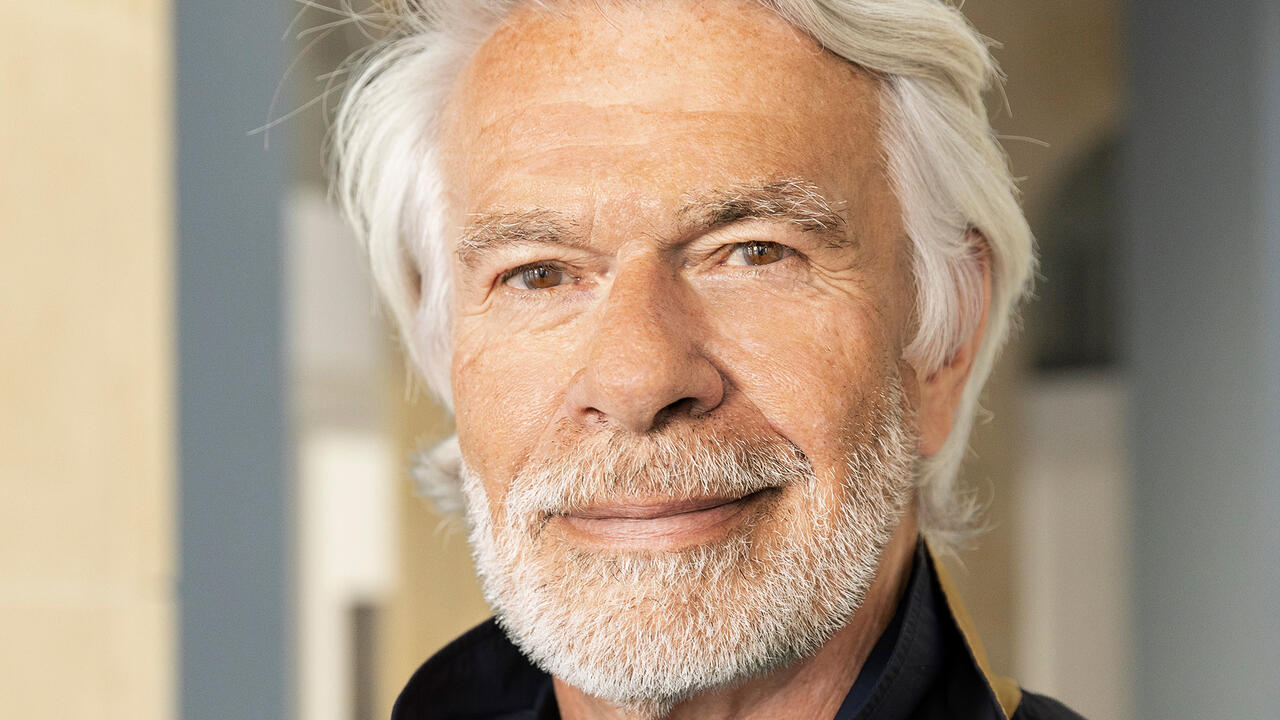

Main image: Ilya Khrzhanovsky, DAU, 2019, film still. Courtesy: Centre Pompidou, Paris