David Hammons's America at The Drawing Center

David Hammons’s early work on view at The Drawing Center during Frieze Week

David Hammons’s early work on view at The Drawing Center during Frieze Week

David Hammons was just three weeks past his 23rd birthday when he watched Los Angeles burn. On 11 August 1965, the artist’s adopted city erupted in violence after police officers brutalized a young Black man whom they pulled over for reckless driving. In response, arsonists torched Black-owned businesses and other property. The Watts Rebellion, as the unrest became known, ended five days later when members of the Los Angeles Police Department and California Army National Guard killed 31 people and arrested 3,338 others. The uprising had a profound impact on Hammons, whose earliest works on paper were developed while he was a student at Otis College of Art and Design from 1968 to 1972.

‘David Hammons: Body Prints, 1968–79’, the first museum exhibition dedicated to those early works, confirms that Hammons captured the trauma and defiance of the Black community in South LA more viscerally than any other art of the time. Moreover, 56 years after the Watts Rebellion, with a painful awareness that the same racism still persists in the US criminal justice system, Hammons’s attention to inequality and injustice feels as potent as ever. In the earliest work on view, Black Boy’s Window (1968)–where a body with two hands raised above its head is silkscreened in black on a pane of glass–you can almost hear the refrain of recent Black Lives Matter protests: ‘Hands up, don’t shoot!’

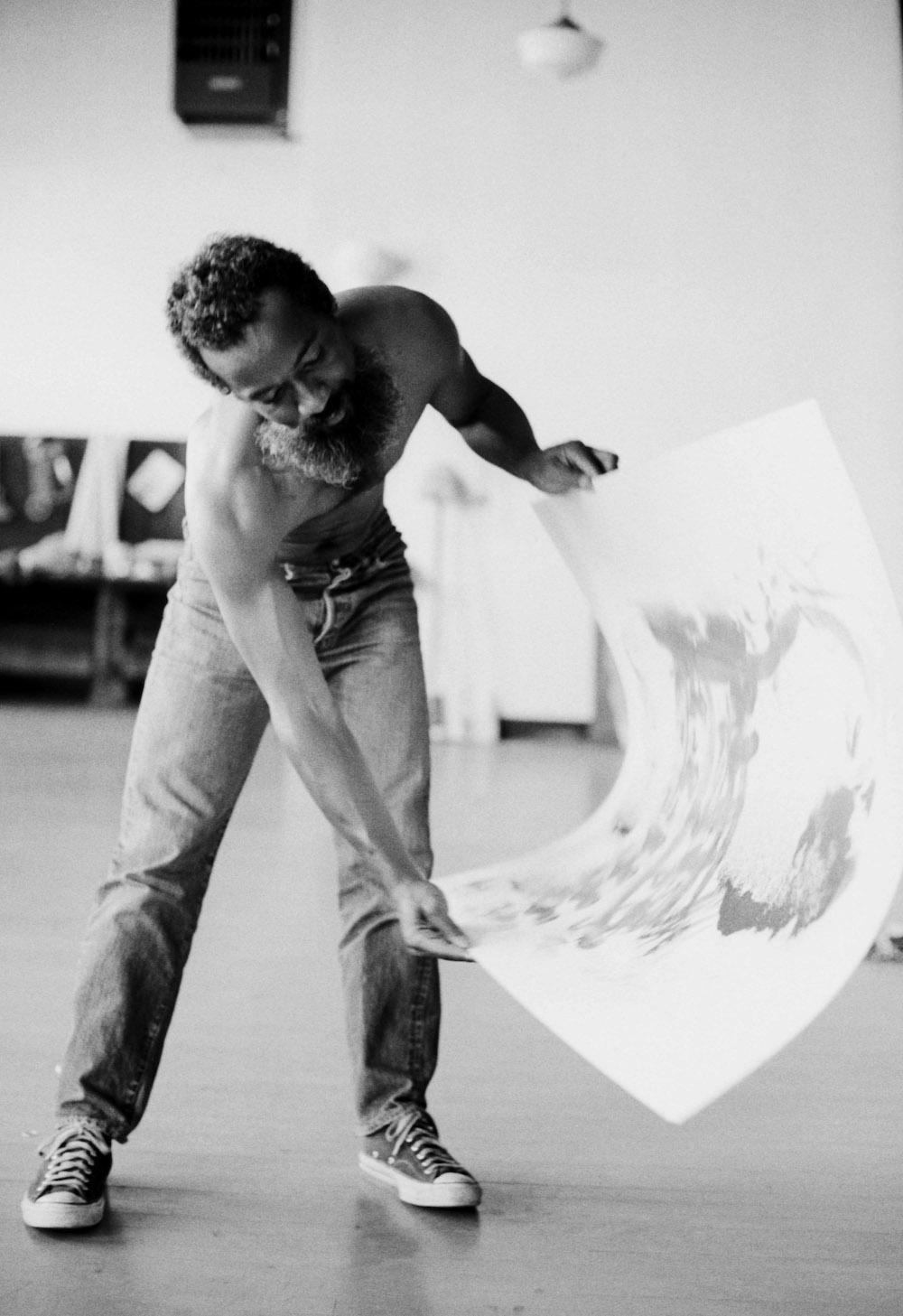

Though these works contain references to Yves Klein’s Anthropométries of the 1950s and ’60s and Romare Bearden’s photo-montages, Hammons’s formal invention gives the ‘Body Prints’ a singular quality. In place of traditional printmaking processes, Hammons slathered his own body in margarine. Once buttered like a biscuit, he’d press himself against paper, which, when dusted with powdered pigment, revealed astounding detail: each individual hair and pore rendered in vegetable oil with near-photographic precision. A series of photographs by Bruce Talamon, taken in the artist’s Slauson studio in 1974, opens the show; in them, a shirtless, oil-slicked Hammons lowers himself onto a piece of paper on the floor. The muscles in his back visibly tighten in a distorted push-up motion, an intense physicality that informs the printing process. Endowing his prints with the gravity of his entire being, Hammons evokes the Black people who put their own bodies at risk of injury and arrest during the marches, sit-ins and strikes of the civil-rights era.

Like the chicken wings that Hammons incorporated into his sculptures of the 1970s and ’80s, margarine was a transfer medium that could be found in even the poorest pantry, and these works feel embedded in the textures of urban poverty, which Hammons witnessed from his studio on Slauson Avenue. The Wine Leading the Wine (1969)–is a tragicomic emblem of inner-city life, depicting two drunks–one sipping from a bottle of liquor in a paper bag, the other gripping his shoulder, following blindly; in Feed Folks (1970), the faces of starving children have been silkscreened around a figure holding a wrapped can of beer. A US flag hangs like a curtain in the background, suggesting that, for some of the country’s poor, the twin blights of alcoholism and hunger have turned the American dream into a nightmare.

The stars and stripes repeatedly appear, for instance, draped around the shoulders of a man in Untitled (Man with Flag) (1975) who, with his strong cheekbones and natural hair parted down the middle, resembles abolitionist Frederick Douglass. In a 1852 speech, Douglass asked: ‘What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?’ Like the nation’s Independence Day, in Hammons’s hands the flag is less a symbol of liberation than mourning: worn not as a proud mantle but as a straitjacket. In 1976, the year of the US bicentennial, Hammons printed faces wearing the trim of an African kufi hat onto a map of the US, shaded the red, black and green of Black nationalist Marcus Garvey’s 1920 Pan-African flag. Bye-Centennial (1976) appears in a back gallery at The Drawing Center, alongside body prints from the late 1970s. In 1990, Hammons would famously lay the same Pan-African colours atop the US stars and stripes in his iconic African-American Flag, transforming a symbol of white imperialism into one of Black solidarity.

Yet, it’s a series of works completed on black paper that look the most stridently political in 2021: the squashed faces within them disturbingly evoking the recent murder of George Floyd, who suffocated on the asphalt of a Minneapolis street beneath police officer Derek Chauvin’s knee. The country still burns. From behind panes of museum glass, many figures here push towards us, as if trying to break free.

This article appeared in Frieze Week, May 2021

Main image: David Hammons making a body print, Slauson Avenue studio, Los Angeles, 1974, digital silver gelatin print, 41 × 51 cm. Courtesy: the artist and The Drawing Centre, New York