David Musgrave

greengrassi, London, UK

greengrassi, London, UK

A couple of years ago, in response to my teasing him about the continuity between his personal appearance (sandy hair, a predilection for soft camel sweaters) and his work (a fondness for masking tape and faint, taupe drawings), David Musgrave replied, 'all colours dream of being beige.' Not only did this remark imply that colours could dream but even more bizarrely, that scarlets and turquoises really hanker to be pale and nondescript. It's a statement that expresses the strength of Musgrave's work: an imaginative play of proposal and inversion; a defiance of easy categorization and hierarchical assertion which hints at absurdity yet is gently and precisely achieved.

Musgrave's work eludes - albeit very self-consciously - a particular type of pinning down. His solo show at greengrassi set out four precise proposals in the shape of four entirely self-contained pieces packed with suggestion and allusion. Tape Figure Twisting Through Space (all works 2001) winds its way up - or is it down? - the wall. Two bands of alternate grey and taupe delineate what appears to be either a twist of packing tape or the scientific curl of a DNA strand. I knew that the wall painting resembled stuck down tape but it has to be pointed out that the spiralling form also describes an upside down figure - a head, some arms, a torso and flimsy legs waving almost translucent toes in the air. Suddenly your view expands as Tape Figure defies gravity, hovering in space with the elegance of an accomplished gymnast and confounding perception with the brain power of a chess master.

I preferred the more robust but equally weird Monster. This little creature - could you call it sculpture? - was fixed to the wall like a trophy; the bastard offspring of Damien Hirst and an autistic hobbyist. Like Tape Figure, Monster proudly delineates something, revealing its dissected innards and jaunty penile extension; again there's a fetishizing of materials, its straining form picked out in epoxy putty and polyurethane paint. Monster is a solid mass but indicates a cartoonish figure originally developed from a figure drawing done blind; it's multi-layered but slightly pathetic; believable but impoverished; how could something so clever be quite so stupid?

Anthroposomething is a small drawing which repeats this discontinuity between image and referent in the attempt both to delineate a thing and to formulate itself. The artist crudely moulded clay and then meticulously made a graphite drawing of it, the blobby word 'Anthroposomething' forming a shape on a square of paper. The laborious craft of the artist's task highlights the puritan perversity of his intention; the investment of meaning is beyond depiction, the sense of value located elsewhere.

It is difficult to articulate the drive and effect of Musgrave's practice. His work can't be explained with a simple 'about', as in 'it's about material' or 'about drawing' or 'about representation or the figure'. He challenges your desire for fixed meaning while constantly tantalizing you with myriad possibilities. How precise do you need to be? How much meaning can you suggest with the slightest of means? What is the artist's work for? How might you spend time and what is the value of that time? His work is in no way ambiguous, for if it could be about something it would be what we could hardly begin to imagine that 'about' to be; the complications of language, turning things upside down and back to front in an attempt to examine the absurd and poignant limits of representation more closely.

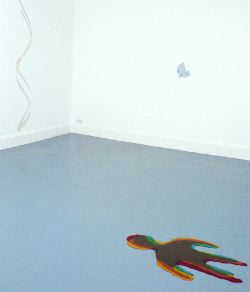

I like to think that greengrassi's chic Georgian environs used to accommodate ladies engaged in needlework and other leisure pursuits in order to pass the time. Musgrave seems to be engaged in a similar and no less worthy pursuit. It might be strange to bring such a dandified character as J.-K. Huysmans into the equation, but for Overlapping Figures, a piece of multicoloured Perspex that delineates a figure lying on the gallery floor and is, for Musgrave, akin to a full blown riot. The colours - blue, red, green, yellow - shimmer around the edges and blend in the middle to create a sludgy brown mass. This figure signals both the futility and the gloriousness of Musgrave's project. Like the tortoise in Huysmans' Against Nature (1884), weighed down by rubies and sapphires, you don't know whether it died from its bejewelled carapace or whether it just passed out from exhaustion at the sheer exquisiteness of simply being alive.