Condo London

greengrassi and Corvi-Mora, London, UK

greengrassi and Corvi-Mora, London, UK

The third edition of Condo London – an initiative that sees local galleries host international colleagues – is taking place across 17 citywide venues, with 46 galleries either dividing space or co-curating exhibitions. One of the standout shows, and a testament to the latter approach, is at greengrassi and Corvi-Mora, who are hosting JTT (New York), Lomex (New York) and Proyectos Ultravioleta (Guatemala City).

The exhibition opens with works on paper by Tatsuo Ikeda, presented by greengrassi. Realized between 1956 and 1985, the 89-year-old’s works are by far the earliest in the show. Belonging to a generation that endured World War II and the unfolding Cold War in Japan, Ikeda joined other artists in developing a pictorial language that would convey contemporary realities while distancing itself from social realism. His monstrous, misshapen human and animal figures – in works such as Family from Chronicle of Birds and Beasts (c.1956) and Warau Hito (Laughing Man, 1957) – are rendered with uncanny precision, giving sinister shape to postwar anxieties. Later compositions – including Edo ↔ Tokyo (1985) and Mienai Toshi (Invisible City, 1977), which weaves an eyeball, seashell and labyrinthine city into a spiralling, dream-like orb – similarly twist recognizable forms, engaging with ideas of human consciousness and an interconnected cosmos.

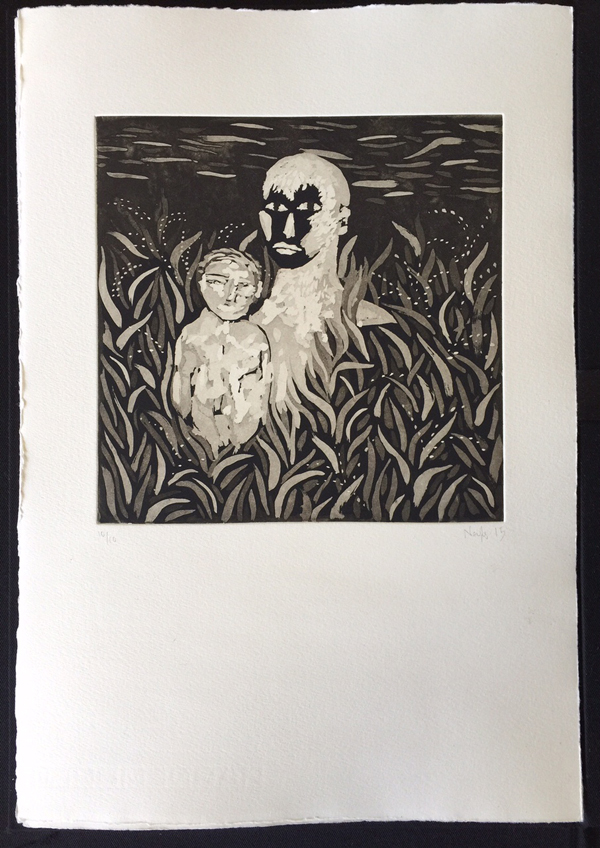

Bodies splinter in Naufus Ramírez-Figueroa’s series of aquatints, ‘Corazón de espantapájaros’ (Heart of the Scarecrow, 2015), as the scarecrows disintegrate, revealing their bones and hearts. As with Ikeda, there is a political undercurrent in Ramírez-Figueroa’s work – shown here by Proyectos Ultravioleta – which was followed by his eponymous performance at the 32nd Bienal de São Paulo in 2016. The pieces are inspired by a 1975 student production of Hugo Carrillo’s 1962 play of the same name – a protest of Guatemala’s repressive government, the re-enactment was met with brutal censorship. Unsettling and melancholic, the prints counteract this attempt at erasure, attesting to the memory of repression, resistance and political theatre in the artist’s native Guatemala.

Violence seeps into an exquisite miniature by Imran Qureshi, represented by Corvi-Mora. Titled Portrait of an Anonymous Person circa 2009 (2017), the work is rendered in the style of Mughal miniaturists (16th–19th century), though its subject wears contemporary dress. A splash of blood-red paint obscures the figure’s face, blooming into a delicate floral pattern that finds translucent echoes in his pale blue sweater and around the oval’s edge. Kye Christensen-Knowles’s paintings, shown by Lomex, foreground the expressive potential of the human body. His Cronus Contemplating Patricide (2017) builds pathos through straining fingers and tense, elongated limbs, while a meditative self-portrait (Self, 2017) suggests intimacy through the artist’s sinewy, bent back.

Upstairs, JTT present two videos by Sable E. Smith, which follow her text-based Untitled (2017). Comprised of acrylic letters arranged into the shape of a square, Untitled plays with the construction of language, as letters coalesce into meaningful words and phrases and disperse into near-sculptural forms. Enumerating the items that you can bring when visiting a loved one in prison, its contents recall Smith’s experience of her father’s incarceration (‘Five 5 x 7 [inch] photographs […] So how do you choose which pictures?'). How We Tell Stories to Children (2015) also complicates the ability of language and images to construct cohesive meaning: perpetually fragmented bodies move before the camera; the artist’s father begins to tell a story from her childhood, his voice cutting in and out and eventually giving way to music. Men Who Swallow Themselves in Mirrors (2017) looks at the parameters of gangster masculinities, combining footage of gunfire with her father’s warm, humorous account of explaining to his young daughter why he carried a gun (‘I’m gonna tell my children the truth […] I told [her] I was a very, very important man’). As with many of the pieces in this show, questions of identity, violence and social restrictions are rendered more complex, more urgent, through the personal and visceral dimensions of Smith’s work.

Condo London 2018 runs across 17 citywide galleries until 10 February. Head over to On View for the full list of participating galleries and read our Critic's Guide: Condon London for some of the highlights.

Main image: Tatsuo Ikeda, Honou No Uragawa (Behind The Flame) (detail), 1958, pen and ink and watercolour on paper, 26 x 36 cm. Courtesy: greengrassi, London