David Wojnarowicz’s Radical Act of Listening

A newly-published collection of the artist’s journals allows silenced voices to speak

A newly-published collection of the artist’s journals allows silenced voices to speak

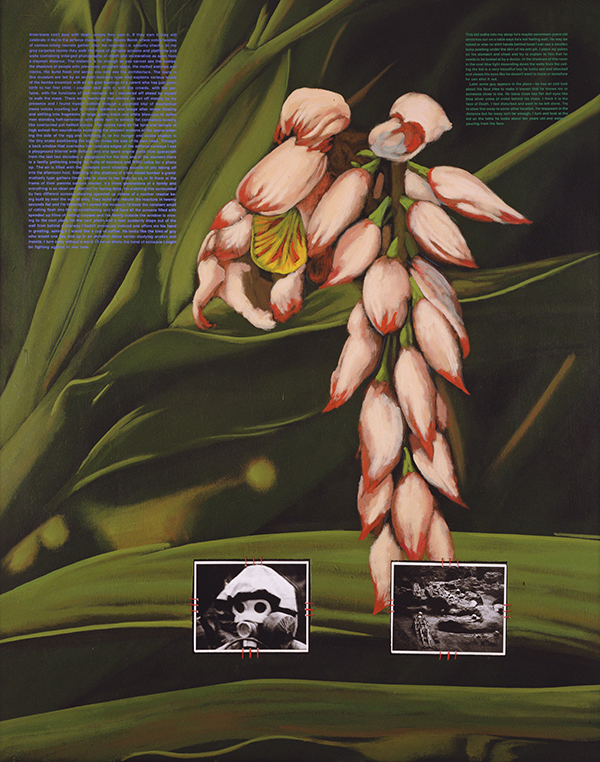

In a photo booth picture taken when he was 13 or 14 years old, David Wojnarowicz’s grin is so wide that you can see his teeth. Thick-framed glasses with Coke-bottle lenses distort his eyes. His pristine polo shirt is buttoned to the neck. Neat, dorky and immaculately clean, you’d think he was a member of a high school chess club, not a street kid who had been beaten up and kidnapped by his alcoholic, deadbeat dad and hustled in Times Square. But, as he told Cynthia Carr, author of the biography Fire in the Belly (2012), he ‘found a good deal of characters who seemed to get a kick out of “corrupting” a young boy’. He turned his first trick aged 12 with a guy he met in Central Park. The man paid two dollars. Wojnarowicz spent the cash on an ice cream sundae. He was just a kid but, as he put it one of his most concise and moving pieces – the 1990 Photostat montage Untitled (One Day This Boy)– ‘one day this kid will talk’.

Wojnarowicz talked like no one else. In poems, paintings, polemics, performances, diary entries and essays, he forged a language of searing rage and emphatic eloquence. His writings fused Beat-generation lyricism to incendiary political satire, augmenting confessional memoir with dreamlike evocations of America’s savage wildernesses and crumbling cities. In doing so, he rightly earned a reputation as one of the most articulate artists and AIDS activists of his generation.

But, importantly, he also knew how to listen. Enthralled by the works of Jean Genet, Jack Kerouac and Arthur Rimbaud, he hit the road in his early 20s, hitchhiking and riding freight trains from New York to San Francisco and back again. He spoke with hobos, truckers, drag queens, hustlers, drifters and other queer kids like him; he cruised in parks and alleys and piers. Somewhere along the way, he began transcribing these conversations from memory, editing out his own voice to allow others to speak, until his journals were filled with first-person monologues. Together, they constituted an impressionistic oral history of gay life in America, albeit one filtered through, and no doubt coloured by, Wojnarowicz’s psyche. In doing so, he nailed to the page something that he would later describe, in his memoirClose to the Knives (1991), in almost numinous terms: ‘something I can’t see or touch but moves in the shape of vowels and uttered sounds like the spinning soft bodies of birds playing with the sky.’

Published this year by Peninsula Press in its first UK edition, and coinciding with Wojnarowicz’s retrospective at the Whitney in New York, The Waterfront Journals collects these monologues in an arresting and timely volume. Originally released in 1982 under the title Sounds in the Distance, the overwhelming impression is not of distance but of a tender and painful proximity. Each is named after its anonymous subject: ‘Elderly transvestite on Second Avenue’, ‘Boy on the Lower East Side’, ‘Man on Christmas Eve along the rainy Hudson River’. (The contents read like a hymn to urban ennui.) In a bar on 42nd Street, a closeted gay man wrestles with internalized shame. ‘I’d lose it all,’ he says, referring to his life as an outwardly straight husband with three children, ‘but I can’t help it.’ Some of the monologues make for disturbing reading. In one, a hustler brings a client (or ‘trick’) to a hotel room. The trick pulls out a knife and slashes the hustler’s arms, spilling blood everywhere, then runs into the street stark naked and disappears into the night.

The cumulative effect of reading these diorama-like pieces – most are barely two pages long – is of a mass of silenced voices beginning to speak; of a chorus as wide as a continent. Most of the monologues touch on sex and cruising, yearned-for encounters haunted by the justified paranoia of being beaten up or arrested by cops, some of which lead to moments of miraculous, redemptive intimacy. In one of the two chapters narrated by Wojnarowicz, he describes a furtive fuck at the edge of a playground: ‘We felt like figures adrift, like falling comets in old comic-book’. The closing words of the journals, by contrast, offer a stark prognostication of his own death in 1992, aged 37, from complications related to AIDS: ‘My eyes have always been advertisements for an early death.’

Decades after Wojnarowicz grinned in that photo booth, he sat for another quite different portrait. In a photograph by Andreas Sterzing, which became the poster for Silence=Death, Rosa von Praunheim’s 1990 film about the AIDS Crisis, he stares at the camera with sombre eyes, his mouth stitched shut by twine, his long, tapered, almond-shaped face hardened by a glare of barely suppressed fury. He is imploring the viewer to pay attention, to refuse to be silenced. The Waterfront Journals are an act of radical listening: preserving voices that would otherwise vanish, bringing marginal histories into the light, making room for the silenced to speak. To make oneself heard against what he termed the ‘killing machine’ of mainstream America was, for Wojnarowicz, a powerful act of defiance. Towards the end of his life, concerned that people affected by the AIDS crisis were falling into despondency, he wondered if they should abandon traditional funerals in favour of something more vocal: ‘a relatively simple ritual of life such as screaming in the streets’.

David Wojnarowicz: The Waterfront Journals (2018) is published by Peninsula Press.

Main image: David Wojnarowicz, Untitled (One day this kid . . .), 1990-91, photostat mounted on board. Courtesy: Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; photograph: © Whitney Museum of American Art, New York