Doclisboa'15 International Film Festival

Various venues, Lisbon, Portugal

Various venues, Lisbon, Portugal

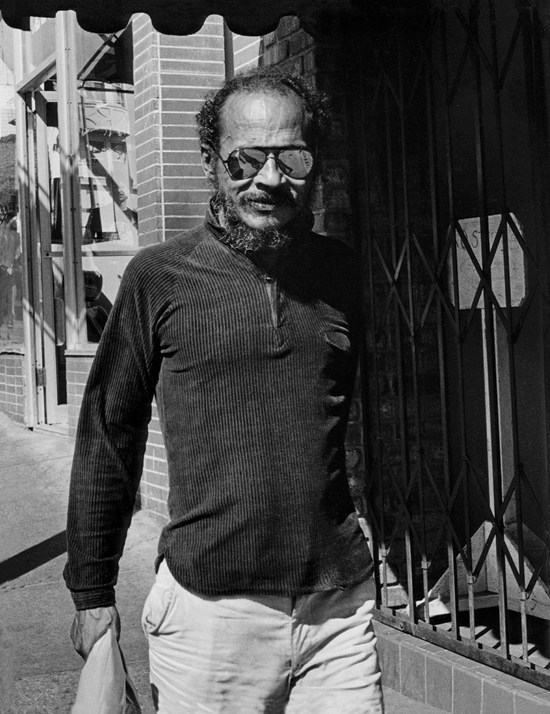

Billy Woodberry’s portrait of the black, Jewish beat poet Bob Kaufman, And When I Die, I Won’t Stay Dead (2015), ends with a Kaufman quote: ‘Would you wear my eyes?’ It’s a challenge that echoes across Doclisboa’s 13th investigation of cinema’s means and modes of documenting and authoring reality.

Directed by Cíntia Gil, Davide Oberto and Tiago Afonso, the festival’s programme frequently looked to history in order to examine the present and questions of political agency. Using the tagline from Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s film The Third Generation (1979), the section ‘“I Don’t Throw Bombs, I Make Films” – Terrorism, Representation’ focused predominately upon cinema’s response to the militant ideological conflicts of the 1970s. A 50-film retrospective of Yugoslavian director Želimir Žilnik offered playful critiques of capital, communism and nationhood. Enacting southern European political solidarity, the section ‘Focus Greece’ gave a backstory to the contemporary positions of Greece and Europe. Demonstrating the festival’s interest in a politics of form as well as of content, the International and Portuguese competitions eroded the distinction between short and feature-length works, resulting in a radically diverse programme pitting films of 16 minutes against those of 150. But it was the vision of specific filmmakers that lingered in the mind, implicitly asking the audience, as Kaufman did, to ‘wear their eyes’.

Anne Charlotte Robertson reflected on her life’s fragmentation through mental illness, with film providing an ordering principal to structure and mirror her existence. Her Five Year Diary (1981–97) – a 38-hour Super-8 opus of which three reels were projected here – is a raw, highly self-aware search for visual meaning, literally for vitality, made yet more complex when viewed within the context of present-day debates about ‘over-sharing’.

Fast-forward a few generations and parallels can be found in Isiah Medina’s first feature 88:88 (2015). Frenetically edited and frequently collapsing into ordered chaos, it refreshingly illustrates possible future directions for digital filmmaking. A diaristic collage of Winnipegian youth culture, colliding mumblecore with the legacy of the New American Cinema Group’s abstraction, the film is only compromised by its occasionally awkward philosophizing and grazing over academic texts, which feel like unnecessary assertions of intellect in an intimate and open-ended work.

Some films extrapolated keenly on the microcosm of the nuclear family. Melding stern voice-over with musical editing, Alex Gerbaulet’s Schicht (Shift, 2015) abstracts the facts of her family’s biography into a socio-political time capsule, reminding us that there is ‘no future without a past’. Olga Privolnova’s Malenkiy Prints (Little Prince, 2015) is a delicately restrained observation of a fractured Russian family and its returning father – an awkward amateur poet and filmmaker – who has cast his children in a cosmic home-movie re-telling of Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s novella Le Petit Prince (The Little Prince, 1943). Chantal Akerman’s devastating No Home Movie (2015) – the director’s final film before her death – is a portrait of her mother that intimates so much more than biography. Discussions of her family’s Judaism and exile are abstractly rhymed with Akerman’s faith in images and a peripatetic lifestyle. As the mother descends into ill health, the camera’s capacity to fix time becomes almost morbid. Yet, throughout No Home Movie the camera remains a vital protagonist; whether roaming as a hand-held visual prosthesis, static and detached like CCTV, eavesdropping on a Skype conversation, or framing the power of landscape.

Frederick Wiseman’s latest film, In Jackson Heights (2015), masterfully inhabits the complexities of the socially diverse Queens neighbourhood of its title. Interned at sea, cinematographer Mauro Herce’s debut feature, Dead Slow Ahead (2015), crafts a sculptural object from a journey on a cargo ship. Eyes are led by the ears via a highly composed musique concrète soundtrack, steering the film’s seductive imagery.

Philippine director Kidlat Tahimik’s epic BalikBayan #1 (2015) narrates the tale of Ferdinand Magellan’s 16th-century circumnavigation of the globe from the perspective of his Philippine slave. Post-colonial historical corrective is rarely as vibrant or humorous as in the singular rough-hewn beauty of Tahimik’s ‘story of a woodcarver’s tale’. The oeuvre of the director – a self proclaimed ‘indi-genius’ (‘indigenous’ + ‘genius’) deserves much greater exposure.

But within Doclisboa’s close examination of the interface of film and reality, it was a rare screening of four reels of Order III (which was first shown in 2008) from the late Gregory Markopoulos’s Eniaios (1948–c.1990) that offered the purest illustration of the medium’s politics and poetics. As across the Eniaios (Markopoulos’ silent 80-hour edit of his life’s work, which has been released in installments since 2004) periods of blank or black frames separate each archival image sequence – most only a few frames long – in a challenging stroboscopic experience. Gibraltar (1975/1989–91) offers a portrait of Gilbert & George, cropped body-parts of whom flicker upon the screen so quickly that any movement, bar the one-off stuttering drag of a cigarette, is barely perceptible. Genius (1970/1989–91) is a Faust-inspired triptych portrait of art dealer Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler and artists Leonor Fini and David Hockney. Images stutter and rotate on screen to highly rhythmic editing. The film fetishizes its spliced protagonists, oscillating from making love to abusing them, always aware of the spectral means by which it transposes the souls it captures to posterity.

To watch these reels is to see, as Mark Webber stated at the screening’s introduction, ‘film as a medium in itself, not a transport mechanism for other stories’. It is to be reminded of the manifold complexities that structure cinema’s ability to make reality visible. It is to watch, in Markopoulos’s words, ‘film as film’.