Documenta 11

Various venues, Kassel, Germany

Various venues, Kassel, Germany

Among the other images charting the utopian aspirations that have animated the city's garden festivals and international art exhibitions alike, the music of Alice Coltrane emanated from several pavilions in the Karlsaue park. And on a screen that appeared to have sprouted out of the ground were a jam jar full of dust from the World Trade Center and a quotation - 'Small pleasures must correct great tragedies' - from the history of landscape gardening that Vita Sackville-West wrote when she created her garden at Sissinghurst in the 1940s.

Where there is much in contemporary art that baulks at the idea that art must 'do' anything, let alone respond to great tragedies, Documenta 11 put forward a carefully composed survey of art that is engaged with the lived experience of the material world. What distinguished this Documenta was not so much the wide-ranging selection of artists from all over the globe as the way in which its outward-looking approach to internationalism was installed as a background feature, throwing the curators' specific conceptual interests more sharply into relief. The exhibition made a convincing case for a view of contemporary art as exploring a genuinely diverse range of social and material conditions, despite the sometimes cumbersome language in which the artistic director, Okwui Enwezor, declared his aim of highlighting the kinds of 'knowledge' produced in the visual arts, on a par with philosophy or science.

Although Enwezor may have been hyped as delivering the 'multicultural Documenta', or 'the post-colonial Documenta', the outcome was an emphatically ideas-driven event that had much in common with the overtly intellectual aims of Catherine David's Documenta 10. Since inclusivity itself has become increasingly commonplace in the art world, certainly since 1997, Documenta 11's 'spectacular difference', as Enwezor put it in the giant catalogue-cum-encyclopaedia, did not lie primarily in the exhibition's generous sense of geography. More significant was the scale of the underlying ambition to stage a critical 'project' in a public arena: the exhibition was presented as the fifth 'platform' in a series of public symposia held around the world over the past 18 months.

In this sense, the overall thrust of Enwezor's initiative was to redress the past exclusions carried out by 'Westernism'. This far-reaching and almost utopian desire to make a case for contemporary art that responds to, even if it cannot redeem, the tragedies of history is very much in keeping with the whole tradition of Documenta. Eager to point out that the exhibition should not be seen as embodying grand conclusions, the show's critique of familiar adversaries - the museum, the canon, the avant-garde - was nevertheless an attempt to update the interaction between art and politics that was itself the motivating force behind numerous Western avant-gardes. Having rejected a chronological arrangement of material, co-curator Carlos Basualdo said the city was chosen as a spatial model for the exhibition because of the open-ended connections or passageways Documenta's audience might encounter as they moved between the works. Regarding the second half of the 20th century as a period in which the West has had to come to terms with the long-range consequences of modernity, Basualdo's evocation of 'the city as garden of memory' could be seen as revisiting the flowers-in-the-ruins model that Arnold Bode put forward when he first placed modern sculptures in front of the devastated Orangerie in the aftermath of World War II.

Alongside the significant emphasis on documentary, spatial topography was one of Documenta 11's clearest overall themes. Zarina Bhimji's film Out of Blue (2002) was a searing portrait of the Ugandan landscape the artist left behind when her family was among those expelled by Idi Amin in the early 1970s. The dry facture of Leon Golub's paintings, next door, had brushstrokes like the tyre tracks on the runway at Entebbe airport. While Destiny Deacon grappled with similar experiences of enforced separation, as did Croatian film-maker Sandja Ivekovic in Personal Cuts (1982), the sequence of places that unfolded in Bhimji's film was devoid of people but invested with a feeling for what could be called the post-colonial Sublime.

The story told in Solid Sea (2001), by the Milan-based group Multiplicity, of the Sri Lankan clandestini who drowned in 1996 when the 'ghost ship' carrying them to Europe sank off the coast of Sicily, was compelling because it had all the elements of a classical tragedy being played out in the context of contemporary immigration. The incident was ignored by the Italian authorities until an identity card was found on one of the corpses brought up by local fishermen. Underwater footage of the wreckage, along with floor-placed monitors featuring witnesses and participants, created an installation whose darkness amplified the importance of sound, so that each of the separate voices could be heard even as the entire chorus was speaking.

The Atlas Group, formed by Walid Ra'ad in 1998, also presented materials found, collected or donated in the course of research. Among the documents was a six-minute video by an unnamed Operator 17, who was supposed to be recording undercover activities at the Corniche seafront in west Beirut, but who turned his attention to filming each day's sunset and was subsequently dismissed. The notebooks donated by Dr Fakhouri included a volume that recorded photo-finish data for a group of Marxist and Islamicist historians who met at the racetrack in Cairo every Sunday for 20 years. An element of intrigue crept into the space between the suspension of disbelief required by the story and one's readiness to accept information about the context in which the documents were found.

The prevalence of documentary clearly had a role to play in showing the range of geographical spaces Documenta wanted to connect, quite literally in the case of Pascale Marthine Tayou, who installed a live feed from the Cameroon which, when I saw it, was showing the World Cup. Sverker Sörlin's summary, in the catalogue, of the landscape studies movement provided an additional context for the mini-retrospective of utopian architecture envisaged by Yona Friedman and by the Dutch architect Constant, who was represented by models, plans and drawings from his 'New Babylon' series (1956-73) showing elevated walkways in cities devoid of traffic. The reconstruction of urban dwellings was addressed by Isa Genzken's models for Berlin, and by Bodys Isek Kingelez' maquette, which (like Molly Nesbit's essay) related to Manhattan after Ground Zero. Sörlin makes use of the suggestive phrase 'interventional carpeting' to describe what artists, architects, town planners and ecologists do when they take an interest in the politics of place, a notion that adds insight to the subjective remodelling of Havana proposed by Carlos Garaicoa as much as it applies to the Tuscany village recreated in the South African property developments shown in David Goldblatt's photographs.

The central presence of Bernd and Hilla Becher in the Kulturbahnhof building, like the punctuation created by Hanne Darboven's grid-based serial works in the Fridericianum and by Frédéric Bruly Bouabré in the Binding Brewery, suggested, however, a broader interest in curating the act of documentation. Several strands of work were underpinned by a process-oriented emphasis on collecting, classifying, sorting and accumulating. Where Dieter Roth, Ivan Kozaric and Chohreh Feyzdjou started with their studio as the chosen setting for duration-based accumulations, Joëlle Tuerlinckx took a walk around a sentence found on a Lisbon church - AQUI HAVIA HISTORIA-CULTURA AGORA 0 (Here there was History-Culture Now Nothing, 2002) - in a piece that documented the artist's investigation of the spatial possibilities of her allocated room. Showing articles of association relating to the public limited company that she set up in such a way that her initial €50,000 investment will permanently avoid any accumulated interest, the documents presented by Maria Eichhorn were interesting because, where Eichhorn's art consists of such ongoing activity, the real-world validity of the actual documents depends on the fact that they are not art at all. In a succinct catalogue essay brimming with ideas Boris Groys argues that the contemporary interest in the ambiguities of documentation could only arise in an age of 'biopolitics', where the Modernist separation of art and life is undermined by scientific, technological and bureaucratic interventions.

The weight carried by documentary film and video, on the other hand, seemed to be split by a curatorial imperative both to highlight artists who move between gallery and cinema spaces - such as Kutlug Ataman, Isaac Julien and Pavel Brãila - and to reinstate the case for the mixture of formal experiment and political inquiry that characterized the idea of Third Cinema. While the latter strand gave contemporary audiences a chance to see whether films by Colectivo Cine Ojo in Chile, for example, had influenced Black Audio Film Collective in mid-1980s Britain, more light could have been shed on Documenta's differential screening conditions. Whereas Jonas Mekas had his films shown in the Bali-Kino cinema, Trin T. Minh-ha's were repositioned as installations in darkened galleries, while Jean-Marie Teno's 16 mm documentaries, like the campaign videos produced by Group Amos, were shown in daylight conditions on monitors in the Documenta Halle.

In one sense this split in the presentation of film-based works carried over into Steve McQueen's installations. McQueen has used 'documentary' before, in Exodus (1992-7), but his work at Documenta consisted entirely of factual material, with rather mixed results. Carib's Leap (2002) came across as a hastily edited home movie and resorted to animation techniques to convey the gravitas of the Grenada landscape in which thousands of Carib Indians chose mass suicide rather than slavery. Taking a camera and microphone into a South African gold mine, in Western Deep (2002), on the other hand, produced one of McQueen's strongest pieces to date, with a pulverizing soundscape adding emotional depth to the juddering images that flicker out of the dark.

So, what happens once you are included? Not a lot, apart from a fresh set of dilemmas. Where Documenta 11 erred on the side of caution, it did so by relying on familiar names from the international biennale circuit, such as Mona Hatoum, Alfredo Jaar and Shirin Neshat, to uphold what is by now a fairly conventional conception of global mélange. Which is to say that any interest in hybridity, or the poetics of cross-cultural translation, was somewhat damped down. Adrian Piper's interest in the colour wheel found in Vedantic mysticism and the Pantone colour system was not really conveyed by her pictures, whereas Jeff Wall could hardly go wrong with a subject based on such a strongly imagistic text as Ralph Ellison's classic African American novel Invisible Man (1952). Fiona Tan updated August Sander's Weimar physiognomy, which was translated from photography to film, and Georges Adéagbo's hieratic display featured portraits of Harald Szeeman and Jan Hoet in the style of popular West African signwriters but, apart from Ken Lum's hall of mirrors pavilion, the carnivalesque spirit of irreverence evoked by writer Jean Fisher, who explores the trickster figure across different cultures, was in short supply. If anything, it was performance art, rather than painting or sculpture, that was sidelined by Documenta 11's sobriety.

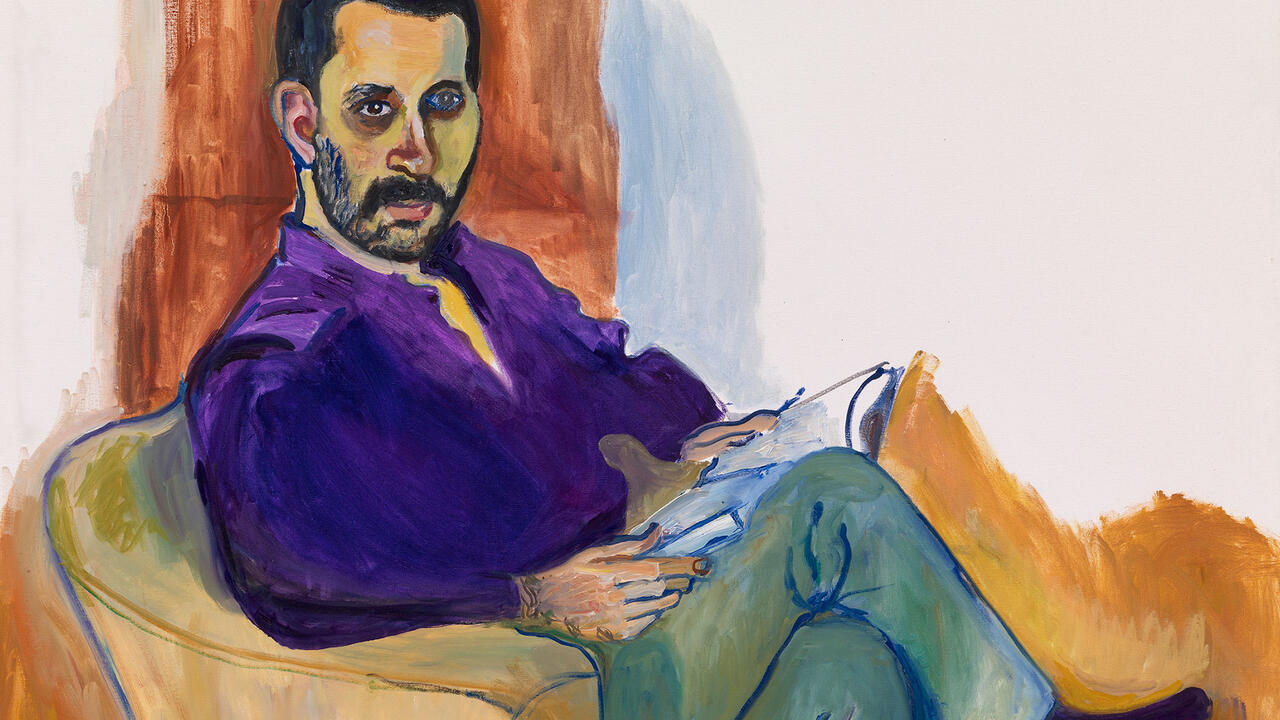

David Small's tactile digital book explored an analytical interest in language that also ran through Ecke Bonk's collection of every Deutches Worterbuch published since 1838. Inspired by the Grimm brothers' fairy tales rather than by their dictionaries, Stan Douglas' Suspiria (2002) featured a randomly generated flow of stories in Technicolor set over a monochrome relay from Kassel's Hercules Tower. But despite the erudite research, it felt as though the artist was doing Stan Douglas by numbers. Indeed, some of the artists associated with the art world's gradual embrace of globalism during the 1990s appear to be a bit stuck. Glenn Ligon has not found a way out of the questions raised by the stencil paintings he began over 12 years ago. Yinka Shonibare took the sexual shenanigans of the Grand Tour as his starting-point. His mannequins are always headless, which draws attention to the wax-print fabric he uses, but in marked contrast to his self-portraiture, which depicts the artist as a Victorian dandy or as Dorian Gray, the avoidance of the face in Shonibare's art-historical tableaux barely conceals the rather one-sided way in which his mannequins are always coded as European subjects.

A week after Documenta 11 opened, Steve McQueen was honoured with an OBE. While his nomination has everything to do with the 'politics of representation' practised by New Labour, which, like other institutions, frequently parades a multicultural exhibitionism that strives to 'show' how inclusive and diverse it wants to be, the artist's acceptance of the award is indicative of the new dilemmas that arise when inclusivity becomes the rule rather than the exception. This suggests that the situation is not one of multicultural normalization gone mad, but one in which perceptions of cultural difference are still subject to someone else's spin. Strangely enough, in the 20 years since writers such as Edward Said and Gayatri Spivak first defined the field of post-colonial studies, language remains an awkwardly unresolved issue, for the discourse surrounding Documenta 11 unwittingly revealed that there is still no satisfactory or widely agreed vocabulary for dealing with 'difference' in contemporary culture. More encouragingly, the repertoire of ideas explored by Sarat Maharaj, whose writing is influenced by Gilles Deleuze and Marcel Duchamp, and who sees otherness as a 'dissolving agent', offers a more speculative and nimble alternative to the congested amalgam that often arises when theory-lingo meets UNESCO-speak. Maharaj's concept of 'xeno-sonics', as performed by the Turkish jokes in Jens Haaning's audio piece at the top of the Treppenstraße, could possibly explain why the visual arts have been historically slower in accepting the creative inclusion of different cultures such that 'world art' still sounds odd whereas 'world music' is commonplace. Attempting to hold open a space for such unresolved debates in the present context of the public sphere, Documenta's desire to redeem 'difference' inevitably revealed a persistent fault line that cuts between the huge questions of global politics and the small pleasures offered by art.