A Dream Journal of the HIV/AIDS Crisis

The novelist and poet Robert Glück revisits dream journals left by his late partner, the painter Ed Aulerich-Sugai, whose life was cut short by HIV in the early 1990s

The novelist and poet Robert Glück revisits dream journals left by his late partner, the painter Ed Aulerich-Sugai, whose life was cut short by HIV in the early 1990s

On a cold August night in 1970, after seeing Paul Morrissey and Andy Warhol’s new film, Trash, at the Centro Cedar in San Francisco, I shared the streetcar stop on Market with a young Asian American. His face was delicate and dramatic, with lush lips. His heavy hair fell past his shoulders and he was absolutely thin. He wore a blue pea coat. He told me he’d noticed me at the theatre. He asked: ‘Are there other movies like that?’

Later, we had coffee at Zim’s on Van Ness, now vanished. His name was Ed Aulerich-Sugai. Ed showed me his sketchbook and I could see his lyricism and intelligence. I gathered that he’d hitched to the city from Tacoma a few weeks before. He’d lived out of garbage cans, then moved into a man’s flat on 18th Street in the Castro. Ed was vague about the details – I surmised that he was trading sex for food and shelter. Did his host think it was romance? I had just moved to San Francisco as well, and was crashing with friends of my cousin. Few people knew I was gay. Ed visited the following night. Outside my door, the friends whispered: ‘Are they having sex?’ Ed was 20; I was 23. I put his cock in my mouth but gagged. Ed’s flesh was beyond value; my own reeked of failure but was too precious to risk. I didn’t know that giving him pleasure meant exciting all creation. In the morning, Ed told me his dream and the dream before that, backing into the night. Not shreds, but cinemascope.

Ed painted me in an ecstatic jungle of ferns. What did the ferny jungle mean? Did it matter? It was okay to be homosexual there. (I wrote in my own work from the time: ‘My American body opalates under this sunlight of warmth.’) Our sex became the opposite of the drudgery of having no identity and no contact. My poems and Ed’s paintings are dated now, but Ed’s dream journals speak of the era. The paranoia of having long hair in the early 1970s: the intensity, the phases, Vidal Sassoon. The magazines, meetings and demonstrations came later. Ed dyed his hair deep, inorganic cobalt. We weren’t out to our parents. Later we became a voting bloc, readership and market share. It took a year to try anal. Ouch ouch ouch ouch! I felt humiliated and invaded. We didn’t think about it again for two or three years. Ed attended a workshop at Glide Church with his friend Sam – on what subject? ‘Blah blah blah the body.’ An inventor presented a dildo that translated music into silent vibrations. He called for a volunteer. Sam went up and experienced Ludwig van Beethoven’s ‘Ode to Joy’ (1822–24) in his anal cavity while the class watched his italicized expression.

Every morning, Ed told me his dreams. (‘I have the life of knowing you, me alone in the totality of my eyes.’) During the day he hardly spoke. He asked: ‘Do you like the sky?’ – followed by hours of silence. Or, perhaps: ‘You can hear rain, but you can’t hear snow.’ I asked him to describe what we were looking at and he did it with precision. He breathed through his eyes. Compared to him, I was an unsuccessful criminal, trying to steal the future from whatever I saw. Who could I be when my only subject, my only news, was the wound of frantic loneliness? To gain a point of view, I asked Ed to describe me and he said without pausing: ‘High spirited and pessimistic.’ I was a secret from myself, but visible to Ed.

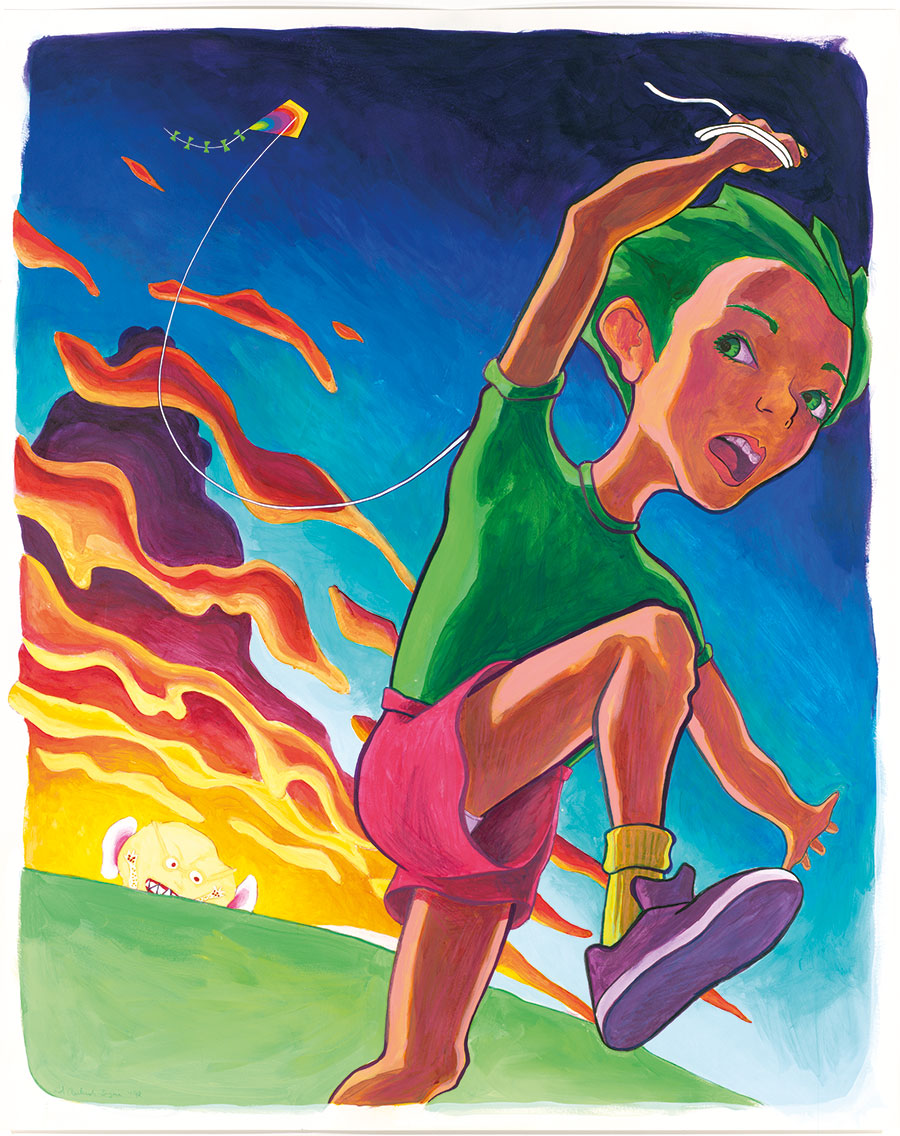

Sometimes, Ed spoke as though language were not a barrier, just as he inhabited the contradictory perspectives of his dreams. I learned from his reply that opposites exist in all of us, sometimes without conflict. We were into the films of Josef von Sternberg and the paintings of Gustav Klimt; overall pattern that induced aching arousal. (‘When the flesh grows dusky and twists with sex and drugs, we scream as much as it hurts.’) Secrets and puzzles, Gérard de Nerval’s Aurélia (1855), intimate distances, the poems of Georg Trakl, Hyperion (1797) by Friedrich Hölderlin. I pushed up from the inside and pressed down on his groin with my palm, mixing inside and outside, gratifying the prostate. In the aroused twilight, slow convulsions, the advent of being like a body torn into existence. Ed moaned – from sensation or idea? We kept the answers in our bodies, but they made no sense. He seemed to know that most situations are hard to fathom because they are simpler than the consciousness that describes them. (‘Be sincere to Bob and Ed, we are the most beautiful type of all, the simple-minded fool.’) Our orgasms only made us hornier, so we jacked off in the dark. Finally, we were rid of tension, held to earth by a thread, floating empty as a box kite. Ed kept a dream journal at my instigation, producing images that I harvested for my poems: ‘A room’, he wrote, ‘appears as I enter it.’

‘Well, sure, I like the sky,’ I replied. The sky looked bored, stolidly overcast, glaring without detail. We stood in front of our stucco apartment building on dreary Masonic and Oak near the burnt-out Haight, a neighbourhood utterly crestfallen. Our windowsills were level with the backyard, where ferns filtered soft dreamy light into our rooms. Was that apartment the beginning of a retreat into the interior that has not ceased? Ed went farther than I, living in rooms like a cat.

We heard gunshots at night (dregs of the ‘Summer of Love’), but it was cockroaches falling from the ceiling into our beds that forced us to move. In 1971, we went to 16th Street, and then, in 1976, to Clipper Street, where I still live. I thought: ‘Stay with him for one more season.’ We ate in silence in a restaurant we couldn’t afford, shamed by the expense. Ed found a note I had written to myself: ‘What is better: being lonely with Ed or lonely by myself?’

Reading Ed’s dream journals again, I am startled by the originals of images that I put in my poems. This task returns me to the labours of our relationship: looking after Ed, anticipating him, trying to make a career happen for him. He sleepwalked into a full scholarship at the San Francisco Art Institute and painted heroic nudes rising and falling through clouds and sky. (‘The expressive body, naked and exploding, arches and twists in space.’) I spent whole seasons inside his paintings and sculptures, driving all over town to find the right watercolour paper and brushes. I went from not having a life to giving it away. Am I writing this for him? His dreams go through me, they place him inside me, the bitterness and chaos of illness, his anger. I’m surprised and even guilty that I often appeared to him in his sleep, as though I don’t allow him into mine.

Most days were surely happier, calmer; I am remembering the cargo I imported into our hippie paradise: I am a superior person who is harmed, etc. I cared less that Ed was fucking so many other men than that I couldn’t manage it myself. Ed lived the era, was committed to it; I, only halfway. Nothing allayed my fear. Nothing touched his solitude. We were made for each other – loneliness so poor it couldn’t afford words. Ed was a hero; all the songs applied to him. Being Asian American, he couldn’t equal our racist community’s self-description – to be precisely a community’s self-description is a kind of immortality – but he parlayed the exotic into glam-rock androgyny: David Bowie. A bar turned Ed away. ‘Why would you reject this amazingly handsome man?’ They didn’t reply, and it took me a minute to understand that it was because he was not white. Ed did not let me see his outrage but volunteered that he had been turned away from a bathhouse, too. Racism in the gay community. We organized a picket line.

Twenty-three years after we met, Ed entered his dreams entirely. He wandered while staying in bed. These were periods of tremendous activity. He generated images to suture an impossible wound. ‘I get scared when I see the dormant garden and the sun so low on the horizon,’ he told me. ‘People die this time of year, responding to a natural cycle, and, when I opened the attic door, my dead body fell into my arms.’ He circled his cell, the condemned spinning out images of dissolution and harm – useless communication, pure communication. Ed’s whole life was a flow of images, visual then verbal, furious and sweet. Image-making and isolation describe my life with Ed. ‘We are a source,’ he said in a dream. ‘May your year be as clear as the glass in your hand,’ he whispered on his last New Year’s Eve, raising his glass.

I want Ed’s experience. A portion belongs to me already, like the paintings he left me. It was hard to ask him to tape our conversations because it meant he was going to die. Was I robbing him of memories? They already seemed derelict, value withdrawn. We were lovers during our 20s, so we grew up together, performing toy versions of our parents’ marriages. (‘My face becomes my parent’s face when it roars down an argument’s Niagara.’) I wish I could convey the feeling of it, lying in bed together in the late morning, membranes humming, the big empty day ahead full of expectation and anxiety. Ed spent money on his clothes, his dope, his hair and his art. He grew marijuana on the back porch under the alien pallor of Gro-Lux. I spent money on things for the house, trips for us, treats. I cleaned and cooked, like my mother. Ed lived for himself, and that was fascinating. (‘With Ed I talk about Ed, his illnesses and his art, his boyhood a bracelet of scissors in the elementary fragrance of blocks and finger paint and his fertility of dreams.’) His indifference to my labour made sense – our household supported his beauty. I nursed a resentment I seemed to need (again, my mother). He would not give up his seat to an old man and said in a cold voice: ‘I paid my quarter.’ The country was still at war.

This article first appeared in frieze issue 210 with the headline ‘Called Back’