Early Years

KW Institute for Contemporary Art, Berlin, Germany

KW Institute for Contemporary Art, Berlin, Germany

Artists have been deconstructing the limitations of the museum’s institutional context for decades, but it is unusual to find the institution itself engaging in this kind of critique. Especially one that doesn’t actually exist yet, or at least whose walls still have to be built. ‘Early Years’ at KW Institute for Contemporary Art in Berlin did exactly this, its title referring not to the early years of an artist’s career, but rather to those of Warsaw’s unbuilt Museum of Modern Art, conceived in 2005 and scheduled to be completed in 2014.

Organized by the museum’s curators (Sebastian Cichocki, Ana Janevski, Katarzyna Karwan´ska and Joanna Mytkowska), ‘Early Years’ effectively problematized the institution from within, showing it to be a framework that is inherently compromised. It presented the museum as a political and economic tool designed to precipitate modernization. But, as an introductory essay in the exhibition’s accompanying pamphlet describes, modernization itself is a divisive, politically fractured goal, not necessarily reconcilable with the aims of the culture it is supposed to frame, never mind the desires of the public at large.

The show featured mainly recent works by 17 artists, most of whom are Polish, though a handful of works by artists of other nationalities address issues specific to Poland. Two works in particular draw a clear picture of the fraught political atmosphere surrounding culture in Poland. The first was Yael Bartana’s Mur i wiez˙a (Wall and Tower, 2009), a video projection that was installed in KW’s large main hall. The propagandist tones of the voiceover describe the return of the Jews to Poland while a group of good-looking young people undertake the construction of the first Kibbutz in Europe in the former Jewish ghetto in Warsaw. The construction process, such as the raising of a barn, swings from cheerful to chilling: as it nears completion, its watchtower and walls topped with coils of barbed wire start to bear an uncanny resemblance to a concentration camp. The project’s Utopian aspect takes a sinister turn as historical precedents, security and territory, constrain the possibility of a return.

Artur Z˙mijewski’s Expelling of the traders from the KDT, Warsaw, Defilad Square, 21st of July, 2009 (2009), meanwhile, provides a disheartening counterbalance. Part of an ongoing series of video works titled ‘Democracies’ (begun last year), which documents political protest, this particular video is explicitly linked to Warsaw’s future Museum of Modern Art, showing the eviction of traders from a building that must be razed to make way for the new museum. As Z˙mijewski trains his camera on the protesters and police in full riot gear, it is hard not to be sympathetic to the traders, who are losing their livelihoods through this political decision. But as a range of historical grudges appear that have more to do with underlying resentments than the actual cause of anger, sympathy becomes more problematic. Raw anti-Semitism aimed at those who want to steal ‘our jobs’ is quickly followed by taunts calling the police ‘Gestapo’. Just who the enemy is gets lost in a bundle of old, inflamed wounds.

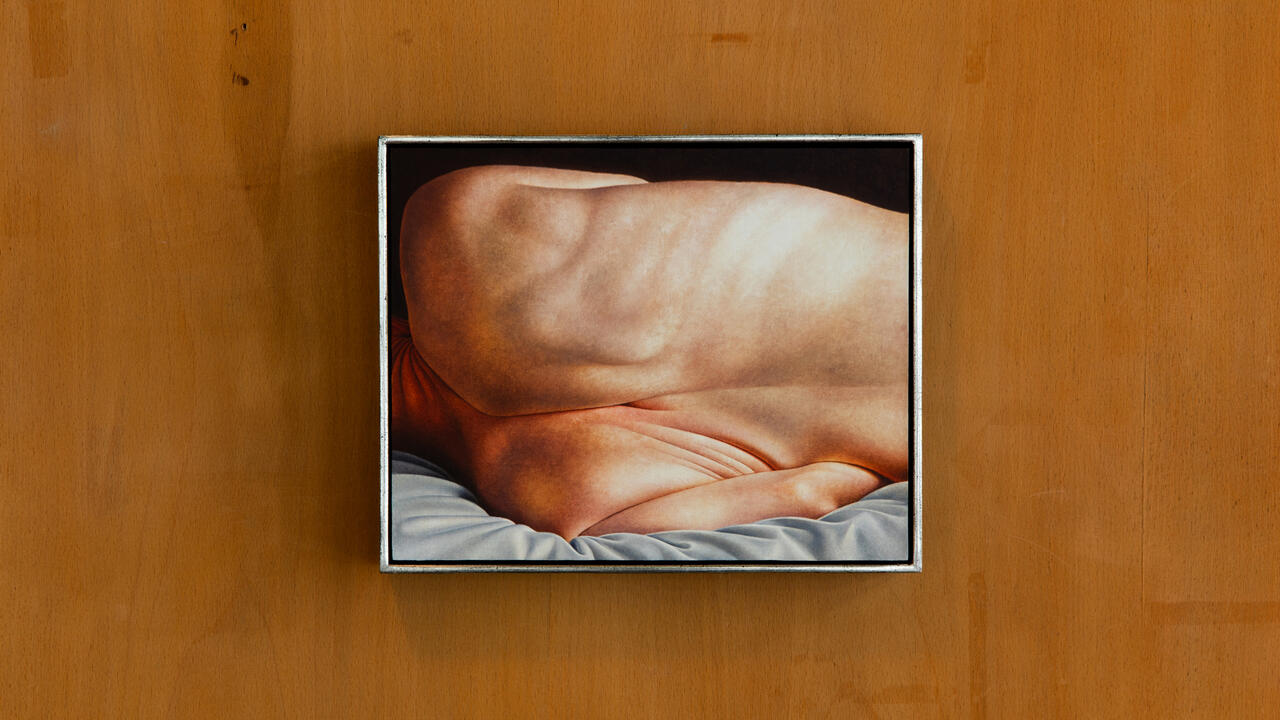

The exhibition’s other works further illuminated the fact that Z˙mijewski’s documentary lays out: democracy, as well as national identity, comprises so many private interests and conflicting opinions that consensus is practically impossible. Poland is pictured as a land of intensely oppositional visions for the future and interpretations of the past. Works by Joanna Rajkowska and Paulina Olowska address the situation of the museum directly, while other pieces take a close look at other aspects of current reality: Ahlam Shibli’s series of photographs of children in Polish orphanages (‘Dom Dziecka’, The House Starves When You Are Away, 2008), or Sanja Ivekovic´’s Invisible Women of Solidarity (2009–10), looking at the forgotten role of women’s political action. The ongoing influence of folk tradition and superstition in contrast to the commemorative function of the art institution is considered in Anna Molska’s affecting film Płaczki (The Mourners, 2010), while personal introspection determines Wojciech Ba˛kowski’s stacatto animated video Spoken Film 4 (2010), in which spoken-word poetry combines with short sketches that accumulate in density, urgency and hopelessness.

In ‘Early Years’, artistic approaches were clearly as heterogeneous as the subjects they address. Authority is a cloudy issue, and it seems impossible to talk about the ‘language of power’ or the ‘voice of the people’ at all, never mind placing them in clear opposition. What emerges instead is the reality of a multi-vocal, conflicting sense of national and personal identity. The future in Poland is drawn as uncertain, if not as apocalyptic as the image suggested by Zbigniew Libera’s People Abandoning the Cities (2009), a photographic diorama like a scene out of Cormac McCarthy’s novel The Road (2006), with people pushing shopping trolleys loaded up with belongings, and kids playing in burnt-out cars.

In this subtle, complex exhibition, the premise did not stifle the works, but rather casted a loose net around these various voices, showing Poland to be fractured but nevertheless politically active – a place where art is entwined with politics, both self-critical and reflective.