Melvin Edwards’s Sculptures Bow Under the Weight of History

At Fridericianum, Kassel, the artist evokes racial power dynamics through objects and watercolours that hint at violence and containment

At Fridericianum, Kassel, the artist evokes racial power dynamics through objects and watercolours that hint at violence and containment

Houston-born artist Melvin Edwards’s first institutional European solo show includes more than 50 works that showcase his ability to provoke a vast range of emotions in his audience. Among other significant pieces on display at Fridericianum, Kassel, are 13 of the artist’s wall-mounted reliefs from his renowned series ‘Lynch Fragments’ (1963–ongoing) – abstract configurations of barbed wire, horseshoes, locks, chains and sharp metal objects that evoke violence. Edwards’s uncompromising aesthetic is driven by his desire to articulate historic social and political injustices – such as those endured during the US civil-rights movement and its parallels in South Africa and South America – to incite viewers to reflect on manifestations of racial violence both past and present.

‘Some Bright Morning’ unites Edwards’s harsh industrial sculptures, which hint at torture and violence, with other three-dimensional works in bolder hues that have softer outlines. Consider the prominent installation Agricole (2016): two dark metallic objects, one with a pointed side connected to an oblong-shaped peep hole, both suspended in mid-air by three chains attached to the ceiling and grounded by another chain with a hook, evoking a scene of torment. By contrast, the canary-yellow painted curves of Augusta (1974) – a tribute to the artist’s grandmother – convey a more cheerful mood.

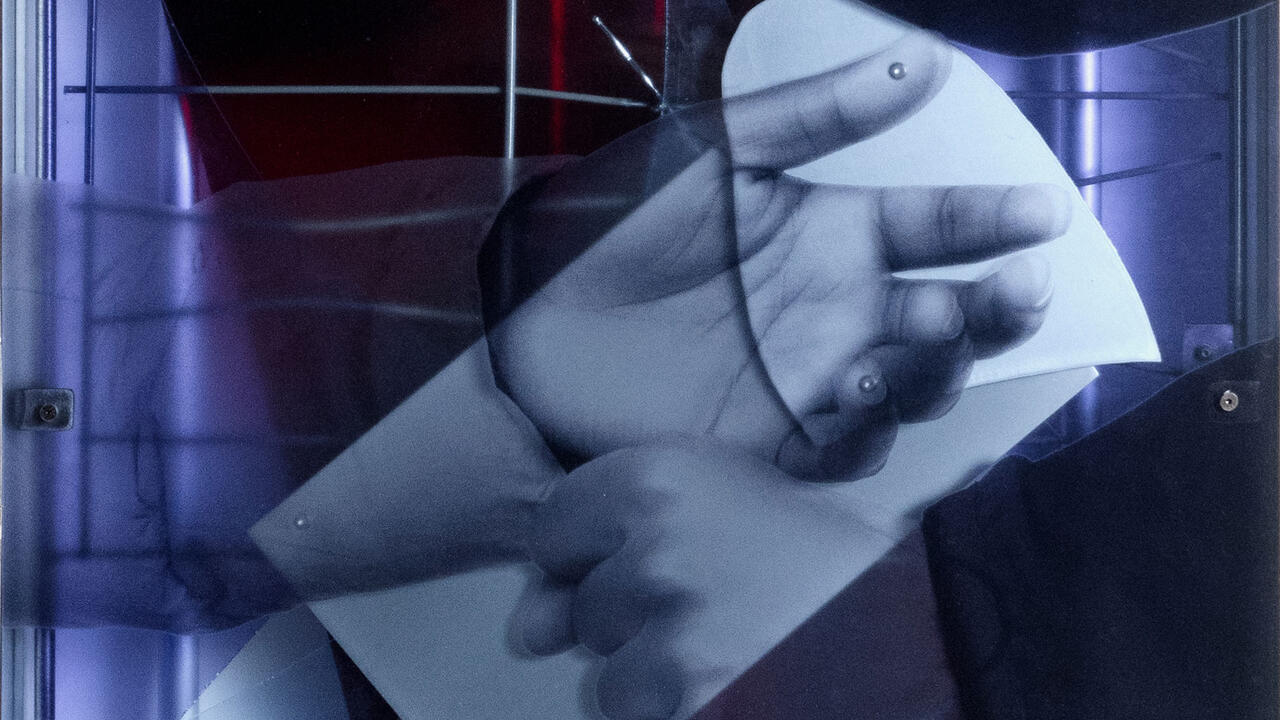

Edwards, who graduated in the late 1950s from the University of Southern California in Los Angeles, established a substantial part of his body of work – his own interpretation of modernism – during the early 1960s. Occupying an entire room of the Fridericianum are the artist’s works on paper, created in the 1970s and 1980s, which are dominated by soft colours and ornamental designs – an ironic juxtaposition to the underlying brute force of his sculptures. Amid their pastel hues, we spot faint silhouettes of barbed wire, fences and chains, suggesting that danger is ever-present. Untitled (1974), a watercolour and ink drawing on paper, resembles the bark of a silvery-lilac birch, with a white chain pattern so subtle that it’s hard to register at first glance. Other paintings in the series are imbued with green and red hues, but the same white-chain pattern persists, albeit positioned differently, hinting at the subconscious restrictions that bind our collective mindset.

By comparison, Edwards’s installations – much like Cameron Rowland’s critiques of the American penal system and economic disenfranchisement, or Cady Noland’s examinations of consumerism and violence in American culture – employ objects such as scrap metal and chains to evoke power dynamics and historical oppression. Edwards extends this discourse by creating sculptures that appear almost to bow under the weight of racial history, transforming industrial elements into symbols of systemic violence and resistance. It wasn’t until 1967, after Edwards moved to New York, that he began using barbed wire to craft freestanding sculptures. These works not only paralleled the urban struggles and racial politics of the time but also reflected the larger discourse of postminimalism, where industrial materials took on a new evocative role in expressing violence. In Felton (1974), a work inspired by his grandfather, Edwards fuses vibrant red with stark, angular lines, evoking both energy and restraint. The piece commands attention, creating a strikingly tense visual experience. Meanwhile Adeoli Goacoba (1988) uses weighty, looming forms and simple architectural structures to effect a haunting, immersive piece that both embodies the gravitas of oppression while allowing space for contemplation.

Each work in ‘Some Bright Morning’ is a testament to Edwards’s socio-political stance. Edwards’s emotionally complex practice ensures that this exhibition reverberates far beyond the gallery walls, leaving audiences to confront the weight of history and the ongoing struggle for justice.

Melvin Edwards’s ‘Some Bright Morning’, is on view at the Fridericianum, Kassel, until 12 January 2025

Main image: Melvin Edwards, Untitled, c.1974, watercolour and ink on paper, 46.4 × 61 cm. Courtesy: the artist; Alexander Gray Associates, New York; Stephen Friedman Gallery, London and Galerie Buchholz, Berlin; photograph: Stephen White & Co