The Fascination in John Coltrane’s ‘Lost’ Album Lies in its Incompleteness

Previously unheard music on Both Directions At Once includes blues as imposing as the saxophonist would ever record

Previously unheard music on Both Directions At Once includes blues as imposing as the saxophonist would ever record

‘Lost’, or previously unheard, albums by the great saxophonist John Coltrane show up relatively often. In 2005, a set recorded by the John Coltrane Quartet at a downtown Manhattan jazz club in 1965 was released as Live at the Half Note: One Down, One Up; in 2014 one of Coltrane’s final concert performances was served up as Offering: Live At Temple University; and in 2015 a definitive reissue of his masterwork A Love Supreme incorporated a rarely heard live performance alongside a bunch of previously unreleased studio outtakes. Such albums are invariably released to tremendous fanfare, only for Coltrane obsessives to claim on internet jazz forums that they are hearing nothing new – this supposedly ‘new’ Coltrane has, in fact, been circulating for years in various unofficial versions of dubious legal provenance.

But Both Directions At Once: The Lost Album (2018) is different. Freshly released last week on Impulse! Records, the set makes available nearly 90 minutes’s worth of hitherto unheard music recorded by the John Coltrane Quartet on 6 March 1963 at the Englewood Cliffs studio in New Jersey. Englewood Cliffs, owned by the legendary record engineer Rudy Van Gelder, was where Coltrane recorded a string of albums that have proved central to the development of modern jazz: Africa/Brass (1961), A Love Supreme (1965) and Ascension (1966), and his quartet in 1963 included McCoy Tyner (piano), Jimmy Garrison (bass) and Elvin Jones (drums), a meeting of profound musical minds and a group of unparalleled visceral force and enduring influence. Little wonder jazz fans have been salivating at the prospect.

The release borrows its title from remarks Coltrane made to his fellow saxophonist Wayne Shorter (who would effectively succeed Coltrane inside a new incarnation of the Miles Davis Quintet). At this point, he inferred, his career was looking ‘in both directions at once’ – much had already been achieved but, ever restless, he was wise to the radical turns his music was about to take. At the Half Note in 1965 we witness him pushing the forms of ‘Afro Blue’ and ‘My Favourite Things’, two longstanding pieces in his repertoire, until their frames buckle; a year later, at Temple University in Philadelphia, we hear Coltrane transcend the saxophone itself mid-solo, creating sound by beating his chest and vocalizing a brutally intense guttural yodel.

Both Directions At Once can’t boast anything quite so striking or unforeseen; Coltrane keeps his saxophone in his mouth throughout and never breaks the fourth wall. Even Ravi Coltrane, Coltrane’s son who helped prepare the record for release, describes it as ‘a kicking-the-tires kind of session’, and some have noised about the necessity of releasing this music. Derek Walmsley, editor of The Wire magazine, tweeted: ‘It is always wonderful to hear new recordings by the great quartet. But it is more of a session than an album; and much of it is familiar if you already love Coltrane.’ Others, too, have questioned whether the jazz critic and author Ashley Kahn might have got carried away with claims, in his booklet note, that the tracks add up to a bona fide album.

But such complaints miss the point. No one would wish away a newly discovered sketch by Leonardo da Vinci because it didn’t aspire to the philosophical splendour of Vitruvian Man. If music by such a transformational artist as Coltrane is out there then it should be made available; and better to do it properly than have the material passed between private collectors in grubby brown envelopes. And then it’s up to us to figure where this new discovery sits within the totality of the Coltrane discography.

Coltrane’s interest in ‘Vilia’ from Franz Lehár’s 1905 operetta The Merry Widow, a contender for the corniest song ever written, might seem unlikely, but the song makes a memorable appearance as a bonus track on the reissue of Coltrane’s 1964 album Live At Birdland and, in March 1963, the quartet deliver an utterly gorgeous performance square in the tenor saxophone mid-tempo ballad tradition of Coleman Hawkins or Ben Webster: Coltrane imbues Lehar’s theme with a soulful wink as he overhauls each note and phrase, claiming its melodic contours as his own.

Looking the other way, forwards into the future, ‘Untitled Original 11383’ and ‘Untitled Original 11386’ both stake out freer terrain. Coltrane’s soprano saxophone and improvizational instincts move from generating lines towards a deluge of stacked-up overtones and crosshatched clusters, the fabric of sound itself; his bass player, Jimmy Garrison, responds with an extraordinary display of twisted, distended tones as he variously drags and slams his bow across, and into, his strings. The longest piece, ‘Slow Blues’, is both ecstatic and incendiary, featuring two Coltrane solos that utilize hollering high notes as architectural markers – an imposing blues as he would ever record.

Could Coltrane have knitted all this disparate music into a structurally robust album? Perhaps not. But the joy and fascination of this new release is precisely its incompleteness: that the music has not been fashioned into any completed form. Calling it a lost ‘session’ might have been more appropriate, implying a chance to eavesdrop on Coltrane and his musicians trying material out: flexing its boundaries, without any of the pressure of ‘legacy’ that inevitably came with a monumental statement like A Love Supreme. But albums, I suppose, are more likely to sell than sessions.

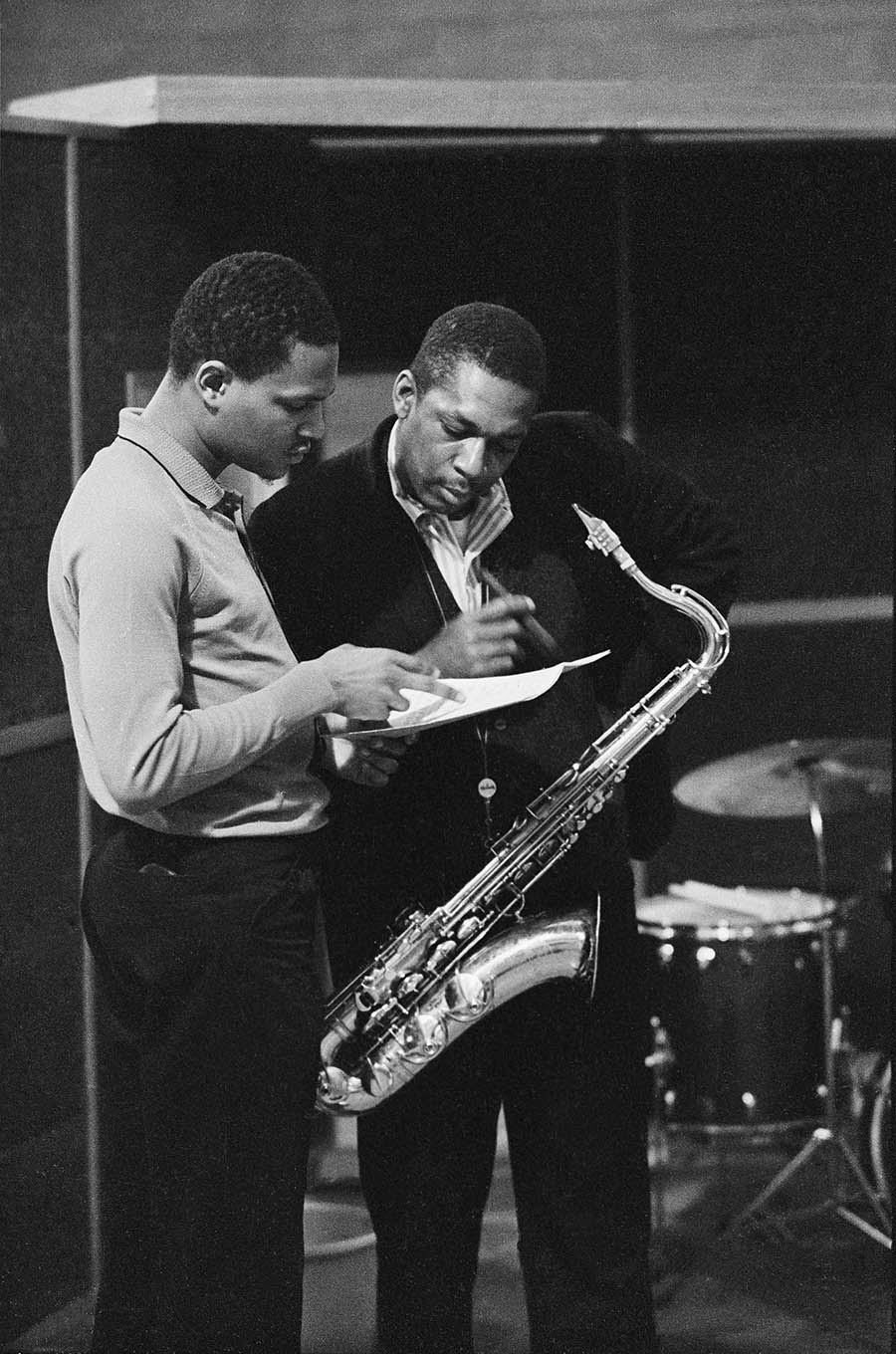

Main image: John Coltrane and band, Van Gelder Studios, 1963. Courtesy: © Jim Marshall Photography LLC; photograph: Jim Marshall