Painters On the Books Every Artist Must Read

Latifa Echakhch, Michael Krebber, Xie Nanxing, Tobias Pils and Shahzia Sikander share the books they frequently return to for inspiration

Latifa Echakhch, Michael Krebber, Xie Nanxing, Tobias Pils and Shahzia Sikander share the books they frequently return to for inspiration

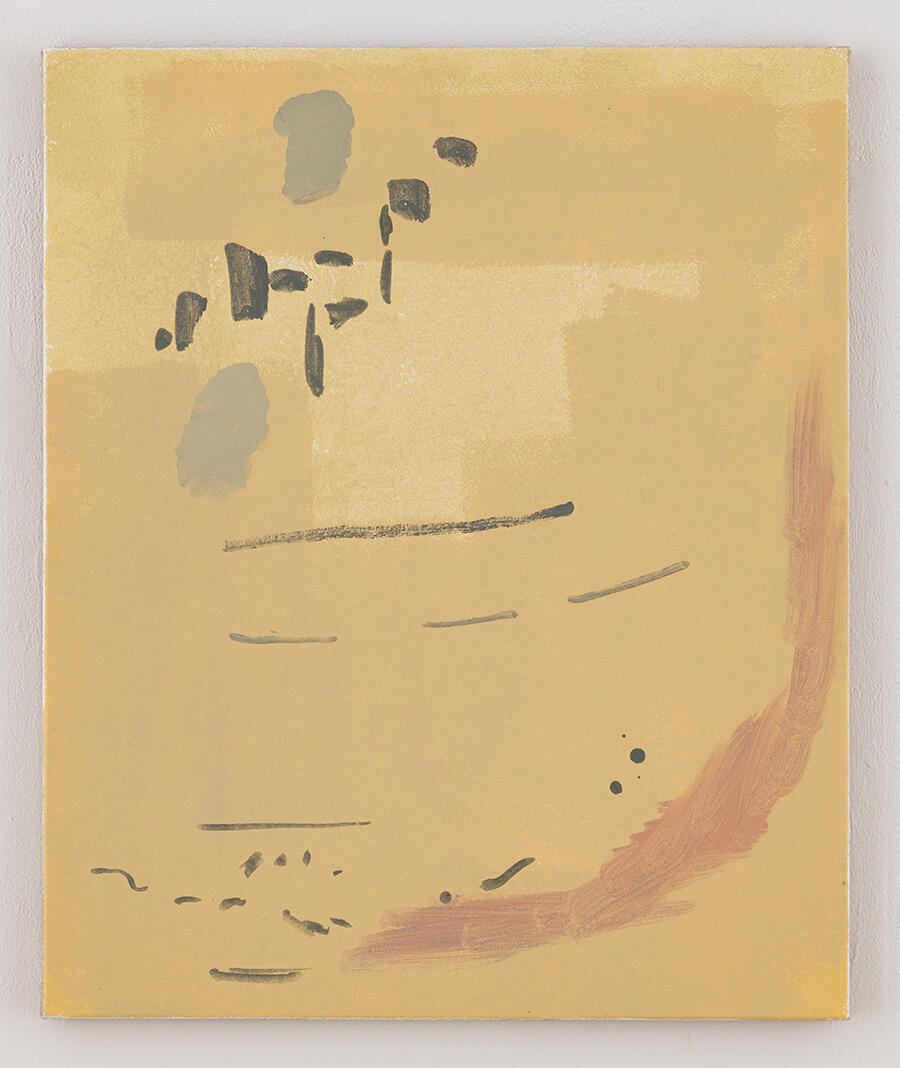

Latifa Echakhch

Over this past year, I have read lots of books about music and sound, and some of my first points of entry on the matter were The Order of Sounds: A Sonorous Archipelago (2016) and The Infra-World (2015) by François J. Bonnet, a sound artist and composer who works under the nom de plume Kassel Jaeger. In these books, instead of analyzing sound as a conceptual object, Bonnet maps a whole universe of experiments, phenomena, philosophical concepts and technologies that brought me a deep awareness of the process of listening and opened up completely new dimensions in my perception of the world.

Michael Krebber

I would like to recommend A Wild Note of Longing: Albert Pinkham Ryder and a Century of American Art (2020), a comprehensive book accompanying the 19th-century American artist’s very charming exhibition at New Bedford Whaling Museum. It was published a year ago, but the exhibition was postponed to this summer because of COVID-19. Ryder was an outsider. In this book, Marsden Hartley, his great admirer, relates him to William Blake, and he definitely belongs to the family of Blake, Adam Elsheimer, Hercules Seghers and, of course, Samuel Palmer. I was told that Francis Picabia also liked these works. I have no proof of this, but it makes perfect sense to me.

Xie Nanxing

A year or so ago, I read Ce que nous voyons, ce qui nous regarde (What We See Looks Back at US, 1992) by Georges Didi-Huberman, which has been translated into Chinese by Wu Hongmiao. I didn’t have any prior knowledge of the author but was drawn to the title. (I have since learnt a little more about him and discovered that, in addition to his extensive writings, he has curated a number of interesting exhibitions.) I felt it might touch upon something that I had previously read about religious paintings: the idea that, for believers, a painting of Jesus was not only an image to be looked at but an embodiment of Christ that would look back down at them.

In fact, the book focuses on minimalism and, in particular, on Tony Smith’s Black Box (1962). Didi-Huberman envelops this work with every conceivable kind of knowledge and analysis, but I feel that, in the end, he is just asking us to really pay attention to how we look at and read art. He explores forms in a way that acknowledges the full extent of their content – formal, historical, mythological, psychological – which resonates with how I think about painting. We shouldn’t be afraid when confronted with unfamiliar forms that we don’t understand because, with time, the forms will speak for themselves.

This made me think about my own practice – how I conceive ideas and how they develop. When I paint something new, the mark that has come from my hand or my mind demands that I study it, that I analyse and try to understand it. Then finally, perhaps, I can make use of it. This process brings me closer to my thoughts and putting all of this into my work helps to create more layers and more possibilities.

Tobias Pils

Agnes Martin: Writings / Schriften (1991) has accompanied me for many years now. Sometimes I open it randomly and read a whole page, sometimes just a column. Its lying around in my studio, quietly talking to me. It’s almost like a physical place I can go to. Maybe the woods. Or it’s like a glass of water. Sometimes I copy passages and hand them to friends with whom I have been talking about certain subjects – like side notes to our conversation, written much more eloquently than I could have said it – as though I’m talking from my soul. I like to think of it as my handbook for spirituality, with methods on how to survive whilst doing this work, teaching me how to get through any circumstance this life brings me. Or, sometimes, it’s just talking to me about formats and formulas. Martin delivers precise statements on artists and their work – on solitude, notions, beauty, inspiration, truth. On friendly scepticism, soft impatience. ‘My paintings have neither object nor space nor line nor anything – no forms,’ she writes. ‘They are light, lightness, about merging, about formlessness, breaking down form.’

Shahzia Sikander

Painting, to me, is like poetry: imaginative and emotional, precise and epic; a profound pursuit for truth and the sublime. I often read poetry to spark inspiration for my paintings. Solmaz Sharif’s Look: Poems (2016) and Derek Walcott’s Omeros (1990) are two timeless and deeply visual poetic expressions that I highly recommend. My paintings also deconstruct traditional South Asian painting vernacular to explore the avant garde. South Asian pre-modern manuscript painting traditions are diverse in their virtuosity. In his book The Spirit of Indian Painting: Close Encounters with 101 Great Works, 1100–1900 (2014), B.N. Goswamy provides a concise and gorgeously illuminated dive into the syncretic tradition of painterly history and process through some of the most iconic works. Last but not least, I want to share Ninth Street Women (2019) by Mary Gabriel. It’s a rich and gutsy account of the turbulent lives, loves and illustrious works of five female abstract expressionist painters: Helen Frankenthaler, Grace Hartigan, Elaine de Kooning, Lee Krasner and Joan Mitchell. I moved to New York in 1997 and caught a glimpse of the shifting art world. Reading this book allowed me to grasp how much the art world has changed in terms of diversity while so much of it remains uneven in terms of gender bias.

This article first appeared in frieze issue 222 with the headline ‘Five Painters on their Favourite Publications', as part of a special series titled 'Painting Now'.

Main image: Latifa Echakhch, ‘L’air du temps – Prix Marcel Duchamp 2013’, installation view, 2014, Centre Pompidou, Paris