‘Open Throat’ Claws at Queer Desire and Ecological Grief

Told from the perspective of a mountain lion, Henry Hoke's hallucinatory novel explores the polycrisis of Los Angeles's unhoused population, wildfires and political violence

Told from the perspective of a mountain lion, Henry Hoke's hallucinatory novel explores the polycrisis of Los Angeles's unhoused population, wildfires and political violence

‘I’ve never eaten a person’, begins Henry Hoke’s Open Throat (2023), ‘but today I might.’ Hoke’s succinctly dazzling novel traverses the familiar polycrisis of Los Angeles through the unfamiliar perspective of a queer mountain lion who uses they/them pronouns. Dedicated to P-22, the legendary LA feline who crossed two freeways as a cub only to end up hostage in the city’s sprawling Griffith Park for the rest of his life, the story merges personal upheaval with political violence, putting the precarity of LA’s unhoused population in dialogue with the bleak realism of the region’s human-caused wildfires. Through the prismatic POV of its grieving, raging and love-hungry lion, Open Throat claws at the productive and painful possibilities of interspecies relationships and ecological grief.

The narrative is rendered fast and sharp in prose-poetry that slips trippily forward and backward in time. It’s riddled with the lion’s playful misinterpretations of passing hiker jargon (‘ellay’ and ‘scare city mentality’ are two such linguistic glitches), along with white-hot one-liners of queer desire and loss that sit heavy in the gut. Open Throat never yields to the pause of a full stop, its wildfire of feeling burning relentlessly until the story’s end.

We first encounter our lion protagonist in their parkland thicket, somewhere beneath the neon beacon of the Hollywood Sign, lurking by a scene of al fresco BDSM content creation. A whip goes up and down, attached to a bulging body with a tantalizing neck vein; hunger stirs in the belly of the beast – and something else, too. For a story largely untethered to linear time or an action-driven plot, the temptation of this vein and the violent capacities of its owner becomes a primary anchor for the narrative, coaxing it on.

As hiking humans come and go, lusting after the therapists they left behind in New York or exalting the ‘perspective’ granted by a lap around this ominous tinderbox of a park, the mountain lion slips in and out of a hunger-driven delirium. They leap for bats, smash lizard skulls, endure earthquakes, dream of ex-lovers and spy on clandestine hook-ups in Griffith Park’s labyrinthine caves. They fantasize and obsess about being full, both of food and love. When this desire peaks, they visit their ‘people’ in ‘town’: a houseless community stationed in the lower edges of the park. Mostly, they try to maintain a starved existence that feels death-adjacent, accumulating exhaustingly un-reciprocable human language in the process: ‘I want to devour their sound / I have so much language in my brain / and nowhere to put it.’

Eventually the chaparral combusts, and the lion is driven down from Griffith Park and into the extreme excess of the Hollywood hills – a very different ‘town’ gilded by spare rooms, luxury landscape lighting and natural disaster insurance. Their journey becomes a seething existential bender. Present trauma resuscitates past pain; abusive memories become zombies, capable of killing all over again. A merry-go-round chocked full of plastic-y, unblinking, impaled animals becomes a worship site for the lion’s ecstatic fantasies of self-annihilation; a zoo is a fun-house mirror that deepens their hunger and self-hatred simultaneously. In his descriptions of such landscapes and encounters, Hoke steers us towards a spectacular space of weirdness; the lion’s confusion and trauma seep into our own, nurturing a kind of interspecies empathy without sliding too far into anthropocentric fantasy.

The magic of this approach is fatefully strained, then, when the lion meets a human and the two worlds must actually interface. Love finally emerges, but it feels much closer to capture. The one-way flow of communication maintained by the narrative – whose protagonist understands human language but can never return it – escalates into an inevitably explosive scenario that blows out of the water any chance of these two worlds integrating, however much the narrator or the reader might crave it. There is a kind of yielding, as Jack Halberstam would frame it, to failure and refusal as queer survival tactics. ‘I have no idea what it’s like to be a person and to be confronted with a me,’ suggests the lion, attempting to explain themselves through language one final time before the system caves in on itself.

One can think of Open Throat as a systems novel acting in reverse, collapsing human structures through a more-than-human perspective. There are traces of Don DeLillo, where the mythologies underpinning human social order are deliciously skewered by a wry absurdism; there are also flares of weird fiction, to the degrees of Jeff VanderMeer and Jenny Hval, where non-human and ecological rage wipes us out like a stack of playing cards. There are softer and more poetic fractures too, mostly rendered in the gentle distortion of language: to the lion, weed-whackers are ‘long sticks with spinning blades [that] send pieces of green flying up into the air’; cars are ‘loud metal boxes’; fireworks are ‘sky fire’; and highways are ‘long deaths’. While there is a generative quality to that which is lost in translation, Open Throat never fully answers the eternally thorny question of how to narrate the perspective of the non-human as a human writer. Perhaps the answer is in its own refusal. When the lion makes their final leap, there is no language left; just a score to settle, and a world to leave behind.

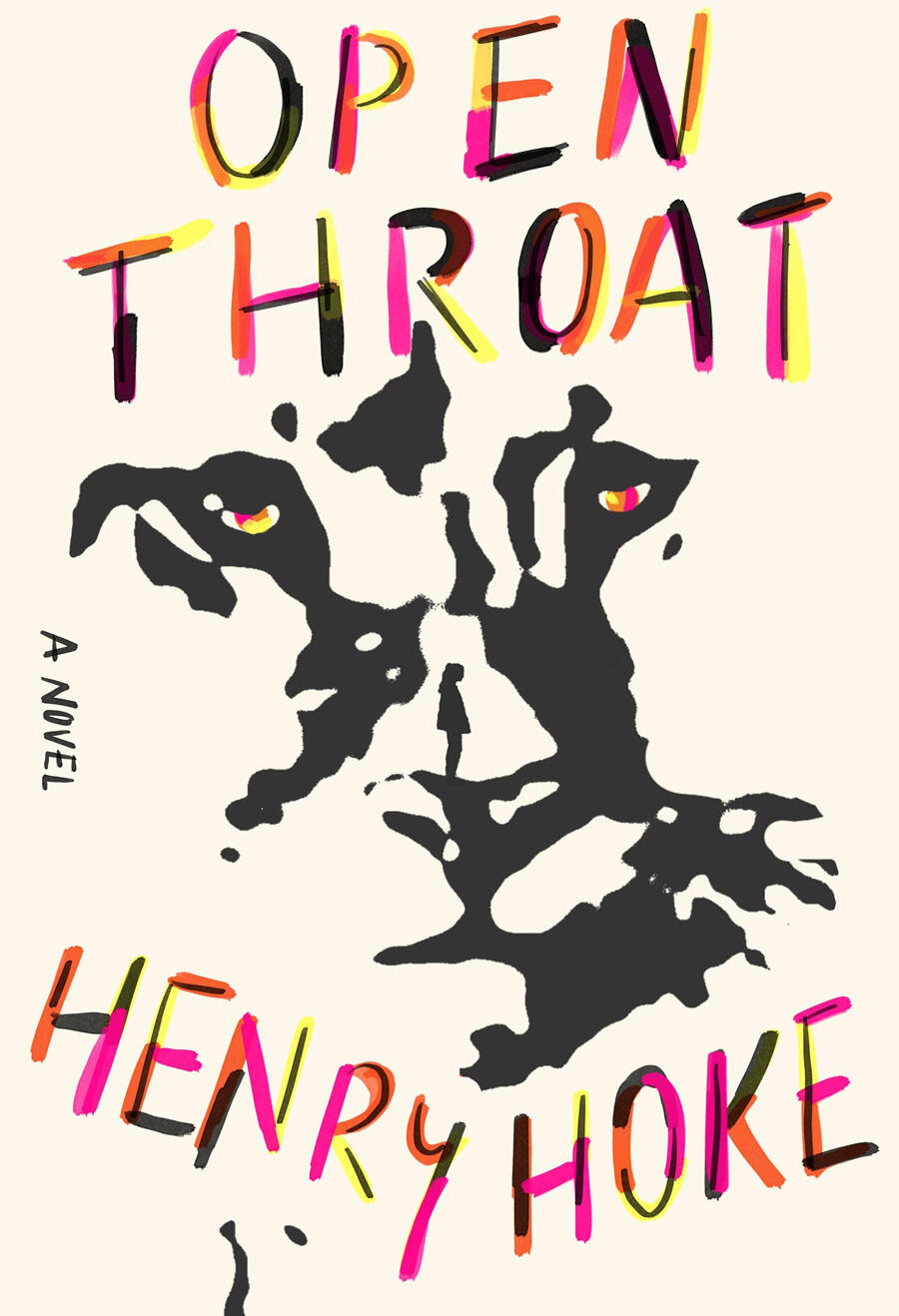

Main image: Henry Hoke, Open Throat, 2023, book cover. Courtesy: Macmillan