In Focus: Ian Cheng

Motion-capture choreography, street fights, Looney Tunes and ‘hybrid cinema’

Motion-capture choreography, street fights, Looney Tunes and ‘hybrid cinema’

New York-based artist Ian Cheng gave up producing popular imagery after a stint at George Lucas’s visual effects firm Industrial Light & Magic. Why, he wondered, should the collective talents of a corps of software engineers go to waste on rendering the hard-edged surfaces of such a conceptually dumb vehicle as, for example, Optimus Prime in the 2007 version of Transformers? Occasionally venturing into painting and installation, Cheng’s primary interest is the disjuncture between physical and digital bodies in space, and the creative potential for 1:1 technical translations between the two. His motion-capture video works feature rough-hewn forms in barren software environments, clipped and energetic film sequences that erupt from the seamless resolution of a digital finish.

Kari Rittenbach What was the idea behind your video work THIS PAPAYA TASTES PERFECT (2011)?

Ian Cheng I wanted to make a corrupted motion-capture choreography based on a street fight that I witnessed, to disrupt this elegant technology – typically used to render graceful action – with something brutal and real. When you push a technology to do what it’s not supposed to, you realize how painfully dumb that technology actually is.

A drunk couple walking out of a bar on Wall Street were almost hit by a car, or at least they perceived themselves to be hit. They stopped the car; the woman took off her heel and stabbed it into the headlights, the man tried to punch through the window. The driver was forced to deal with pure irrationality. There was no violence for a while, just a lot of intimidation, but eventually the boyfriend started to dominate the scene. He tore off his shirt, undid his ponytail, then scooped up the driver and took him to a clearing away from everyone else – like a lion isolating its prey. It was very primal in a way that I didn’t expect, because of the car, which acted as a mediator, forestalling the final violence but also escalating the fear and anxiety and anger of those involved.

Ultimately I’m interested in a type of hybrid cinema – where there’s a real performance that you’re able to map into a world you can fully control. Directing an actor in real space, who has real feedback with objects, allows you to be very physical. Afterwards, when editing this physical record, you’re able to compose sequences of gestures and movement in 4D space.

KR There’s an inept physicality in one-to-one combat that isn’t often represented. How does that compare to video-game violence?

IC Fights in video-games are very efficient. You do a one-two combo: boom, boom. Video-games allow you to exercise what you’re not evolved to do, which is to engage immediately in a fight without any sense of risk or reward. If you die, you start over and try a different route. In reality people have fight-or-flight responses. It would be amazing to have a video-game with a sense of evolutionary awkwardness built into conflict. But probably no one would want to play it!

KR Looney Tunes cartoons have a video-game teleology, too – repeating the same struggle time after time. Bugs Bunny and Elmer Fudd appear in your motion-capture video for the Liars’ single ‘Brats’ (2012). How did you deal with their cartoonish virtuosity?

IC In Looney Tunes there’s a clear set-up and a clear ending: Fudd loses, Bugs always wins. It’s like chess: you can exercise all the different possibilities; the pleasure is in seeing the variations. The narrative isn’t over; I think there’s something more like a synthesis.

I hired professional acrobats to play those characters – their movements are much more fun than THIS PAPAYA TASTES PERFECT and they’re crazier: back-bends and flips. In the end, the Liars video doesn’t play out: Fudd and Bugs are eventually trumped by human characters, the band. The cartoons are trampled because they’re at a comparatively smaller scale in the motion-capture space, a child’s scale. The idea was to introduce a sense of entropy into the closed narrative system, a merciless contingency that the genre of Looney Tunes demands but can’t enact.

[Missing Image]

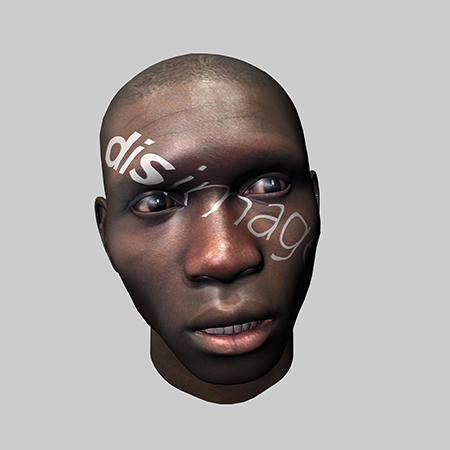

KR Did this contingency inform your work for dis magazine’s stock image website?

IC For DISimages (2013), I scanned fashion models into 3d form. The idea was to surpass the stock image by creating a full-on digital double of each model’s facial identity, downloadable for use. They come with stock phrases too: ‘cash only’, ‘I love seafood’, ‘nature doesn’t care about French people’, etc. Soon celebrities will have to copyright the contours of their faces. In any case I have no idea what contextual home or narrative use these forms will eventually find.

KR What are you working on at the moment?

IC I’m making a series of live computer simulations governed by some basic narrative laws that allow the situation to unfold like an endlessly evolving video. Maybe it’s like being a bad chef. Not really minding the stove but tossing in a set of ingredients, dialling a certain temperature, and just letting it boil to death – or maybe some catalytic surprises emerge.

KR How does entropy fit into that equation?

IC Something I’ve been thinking about in my own work is how American culture has historically hated the idea of chaos. Even if we love our bodies, we always want to be young – to forestall the chaos and entropy of ageing. Art has reacted to this of course; many artists espouse entropy. Robert Smithson, Pierre Huyghe, Reena Spaulings. Paul McCarthy used to perform with his own body; now, in his 60s, he’s collaborating with ex-Disney robotics engineers, really embracing the prosthetics that accompany the body as it ages and fails. But unlike him, I don’t feel the need to express criticality through gestures of defacement.

I prefer the idea that entropy needs to be managed, not only romantically espoused, and especially not feared. The writer and statistician Nate Silver proposes that uncertainty has an increasingly defined shape when you look at it probabilistically; much like in chaos theory, where chaos entropically orbits a resting position. Or soap molecules settling into a perfect sphere.

Perhaps the aesthetic response is to not only be truthful about the entropy of life, but to judo it into something productive. If we can integrate some coefficient of entropy, while anticipating its hidden shape, we can model the look and feel of the future – a society of entropy managers living with and sculpting from the chaos emerging all around us, all the time.

Ian Cheng was the recipient of a 2012 Rema Hort Mann Foundation Award. In 2012 he was included in the group exhibition ‘A Disagreeable Object’ at SculptureCenter, New York, USA; and this year in ‘HMV’ at Foxy Productions, New York. Solo exhibitions in 2013 include ‘The Vanity’ , Los Angeles, USA; and ‘Off Vendome’ , Düsseldorf, Germany. His work will feature in the 12th Lyon Biennial (12 September – 29 December), France, curated by Gunna Kvaran.