In Focus: Liu Chuang

Cold portraits and warm-hearted annotations

Cold portraits and warm-hearted annotations

Liu Chuang’s latest work, Segmented Landscape (2014), consists of six metal window grilles, each bearing a distinct geometric pattern. Installed above visitors’ heads in the main hall of the Power Station of Art, the venue for the 10th Shanghai Biennale, it is lit by spotlights while an artificial breeze causes pieces of white gauze, hanging like curtains behind each grille, to shift gently. The shadows cast by the grilles appear as patterns transposed onto the fabric. The overall effect is of a series of photograms, which seems fitting since the work is, to some extent, a snapshot of China in the late 1980s and early ’90s, when such window guards suddenly began appearing on houses and apartments across the country. At that time, they could be seen as a visual reminder of China’s burgeoning prosperity; here, they seem a quiet lament to the individualization that has been a by-product of economic growth.

Dubbed ‘the factory of the world’, the Pearl River Delta Economic Zone in south-east China is a sprawling urban megatropolis of some 65.5 million inhabitants. Coinciding with the country’s economic boom – resulting from the second stage of Deng Xiaoping’s economic liberalization in the late 1980s – the region’s infrastructure, industry and population exploded almost overnight. Factories were built, high-rises rose and people flocked to fill them. Liu, now based in Beijing, was one of them. After graduating from Hubei Institute of Art in 2001, he relocated to Shenzhen before moving again to the nearby city of Dongguan. In 2005, with the artist Li Jinghu, Liu started a business in Dongguan called Picabia Decoration Co. Ltd. It’s main product: manufacturing decorative paintings to order. The factory closed after a year and Liu subsequently moved to Beijing, but his experience of the region and its unique physical and social transformation continues to mark his work.

As in the case of Segmented Landscape, Liu often works with and within architectural boundaries, isolating and unpacking the systems that operate barely noticed in the backgrounds of our lives. For Untitled (The History of Sweat) I + II (2007/13) he switched the parts of an air-conditioning unit so that the element ordinarily situated outside was placed indoors and the condensed vapour run-off was left to pool inside the room, looking like an increasingly giant sweat patch. Likewise, for Untitled (Unknown River) II (2008), Liu hooked up the main water supply to T Space gallery in Beijing to run via pipes through the hollow-metal, mass-produced folding chairs and tables that were spread throughout the space.

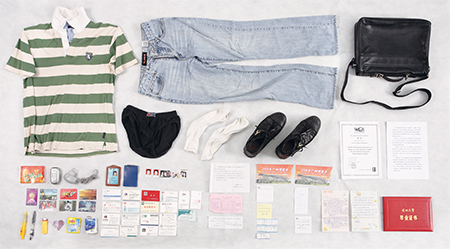

Liu not only opens up architectural systems, but also the hidden social relations inside distributions and flows. For the series ‘Buying Everything on You’ (2006–07), the artist took that unromantic thing, the economic transaction, and made it personal. Liu approached some newly arrived migrants seeking work at the Luohu labour market in Shenzhen to ask whether he could buy everything they had on them, from personal effects right down to their underwear. Amazingly, a few agreed. The highest price the artist paid was CN¥2,000 (£200 GBP); the lowest, a pittance: CN¥350 (£35 GBP). Presented plainly, artefact-like on a board, the belongings resemble oversized parts from a giant model kit or, more disturbingly, exhibits from a crime scene: coldly dehumanized portraits of their owners.

Similarly accumulative and emotive, Love Story (2013) consists of 3,000 pulp-fiction books that Liu bought from the rental stores that surround the factories in Dongguan. He has presented them as a heaped pile (at PKM Gallery in Beijing in 2012), neatly stacked on a table, some copies open (in the booth of his Shanghai gallery, Leo Xu Projects, at Frieze New York art fair in 2013), or with annotations carefully copied out onto a wall (for a solo show at Salon 94, New York, in 2014). Popular among factory workers, these love stories – imports from Taiwan and Hong Kong throughout the 1980s and ’90s – share a formulaic cover design: a lovelorn girl, sometimes two, set against a bright background. The flimsy paperbacks, while no literary gems, contained something Liu found interesting: missives – sometimes short, sometimes lengthy – written by the books’ readers, from letters to diary entries, from heartfelt poetry to doodles and phone numbers. These usually anonymous scribbles, acting as a kind of localized pre-internet comments thread, seem destined to circulate in perpetuity without ever reaching their intended audience.

Liu doesn’t shy away from such awkward interventions. For Untitled (The Dancing Partner) (2010), he instructed two drivers of matching white, nondescript Volkswagen saloon cars to drive at the minimum speed limit throughout Beijing’s chaotic road network. Other road users – initially bemused then increasingly irate – honk, tailgate and angrily overtake the stoic pair who, driving at the same unwaveringly steady pace as though their cars are invisibly linked, apparently oblivious to the trouble they are causing. In a country of China’s vastness, political heft and economic energy, Untitled (The Dancing Partner) is a quietly wry form of transgression. Contrasting the slow, ordered pace of the two cars to the relative chaos of the other traffic, the artist explains the work metaphorically in terms of signal and noise: the poise of the two cars’ quiet dance only becoming clear when set against the background of the busy traffic.

A piece made by Liu on Chinese New Year’s Day in 2011, Untitled (The Festival), recently shown at the 10th Gwangju Biennale, underscores this thinking. Filmed in an industrial area of Dongguan, the artist applies himself to a seemingly unproductive mission. He lights a discarded roll of newspaper but, before it burns out, he uses it to light another, and then another. As he walks calmly along the debris-strewn street, the factories for once stand silent in the background.

Liu Chuang is an artist based in Beijing, China. In 2014, he had a solo show at Salon 94, New York, USA, and his work was included in the 10th Gwangju Biennale, South Korea, and the 10th Shanghai Biennale, China, which runs until 31 March. He will be part of the group exhibition, 'Object System', at Minsheng Art Museum, Shanghai, which opens on 28 March.