Fortress of Solitude

A night at Ricardo Bofill's Barcelona high-rise, Walden 7

A night at Ricardo Bofill's Barcelona high-rise, Walden 7

Approached by taxi at the start of my overnight stay, Walden 7 sprang into sight like a vast, jagged red-clay death star that had run aground next to a Spanish ring road. Designed by Ricardo Bofill with his Taller de Arquitectura group and erected in the Barcelona suburb of St Just Desvern in 1975, the building stands apart in every sense. The 15-storey residential complex was originally intended to be one of five similar blocks, and early photographs show it in the midst of a vast brownfield site. At that point its appearance was akin to its inspiration: a desert rock. Bofill has said that his motivation for becoming an architect was not the built environment but ‘pure nature’, specifically that of the Sahara Desert, where he saw ‘just rocks […] geometric solids in the sand dunes.’ 1 Over the past 40 years, other constructions have clustered around Walden 7, yet they do nothing to counteract the building’s singularity.

Walden 7’s formal oddity is a function of its geometric underpinning. Its basic unit is a 28-metre square cube and its interconnected 16-storey towers (including roof level) are built from stacks of such cells, those on each floor shifted slightly from the ones below. The space created by the incremental displacement allows for a network of walkways, and about half of the floor area of Walden is public space. The complex is entered via a narrow slit that runs several stories high (a feature that is inescapably vaginal). Once inside, the red of the outside gives way to turquoise and azure interiors. There are four internal courtyards that run the full height of the building, allowing glimpses of the sky above, and a set of fountains that play on Fridays to welcome residents home for the weekend (sadly I stayed midweek, so the water feature remained inert).

Bofill’s collective Taller de Arquitectura (architecture workshop) was founded in 1960 and encompassed not only architecture but also poetry, sociology and philosophy. Bofill himself never completed his professional training and the only qualified architect of the original set-up was his sister, Anna. In 1966, the English architect Peter Hodgkinson joined the collective upon his graduation from the Architectural Association and was an important part of the Walden 7 project. Among other members of the team were the literary critic Salvador Clotas, the economist Julia Romea and José Agustin Goytisolo, who was already a poet of some note. Given the nature of this group, it is unsurprising that Walden 7 has a basis in ideas that are not strictly architectural. The name derives from the novel Walden 2, written in 1948 by the psychologist B. F. Skinner. A clunky read, the book imagines a community in which all cultural norms are rejected in favour of a self-enforced, evidence-based code of behaviour. In turn, Skinner’s story refers to Henry David Thoreau’s 1854 work Walden, an account of a stint of two years, two months and two days spent living in a cabin with none of the accoutrements of a mid-19th century middle class life. Skinner borrowed haphazardly from Thoreau, ignoring Walden’s emphasis on introspection, and likewise Bofill and his team used Skinner’s work liberally. Uniting the two literary works and the building, however, is the idea that life should not be constrained by preconceived ideas and that, at its essence, society is a collection of individuals.

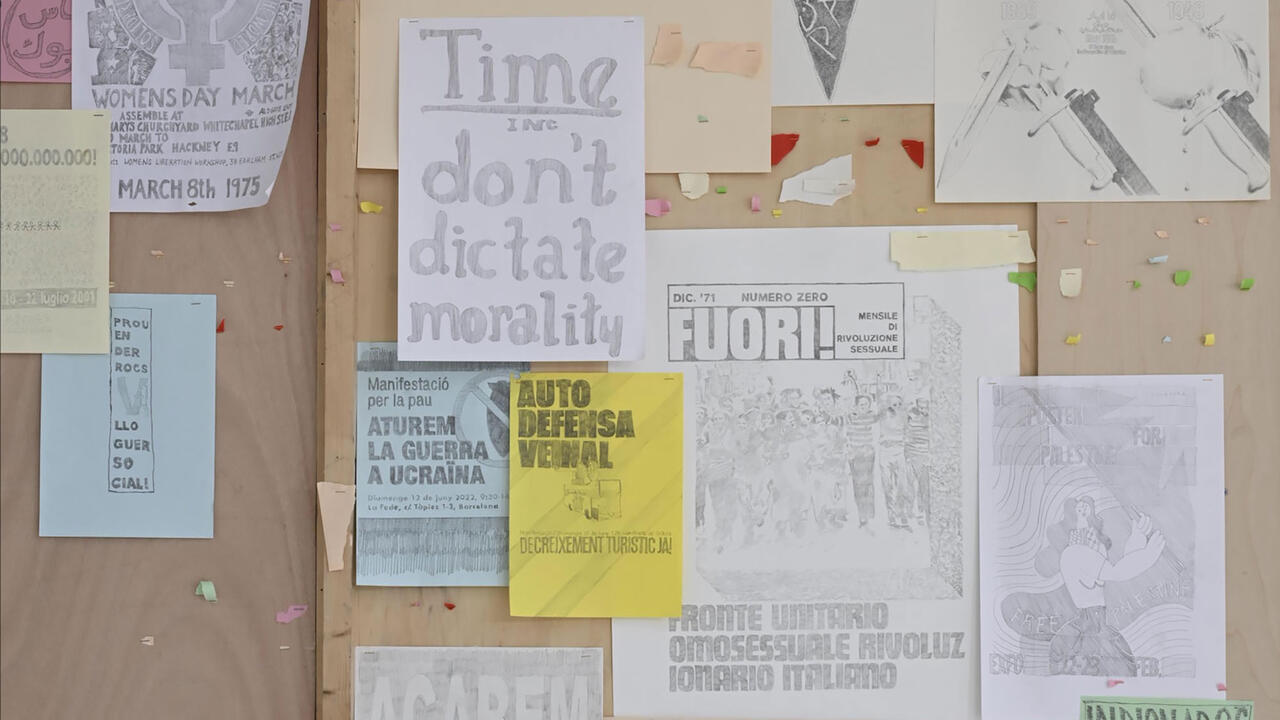

Played out in architecture, this led to the Walden 7 ‘cell’, the idea being that they can be connected and disconnected to suit different life stages or choices. A single person might live in one, while a family might occupy three or four. When children leave home, or a family breaks down, the partition between the individual units can be re-established. Significantly, the family is viewed as a passing and optional phase, rather than the basis of social existence. In the context of mid-1970s Spain, still in the grip of Franco’s dictatorship, this was a revolutionary proposition. The building is still scattered with other manifestations of Bofill’s early radicalism. Chiefly, all of the open-air walkways are named after poets, philosophers, scientists and political activists. I stayed on Poincaré Passage and, in my explorations of the building, I travelled the paths of Jesse Owens, Pablo Neruda, Frank Kafka and Albert Einstein, among others. Meanwhile, the basement car park is embellished with poetry from Goytisolo that touches on memory, fantasy, dreams and terror – appropriate, but unusual subterranean stuff.

Currently there are about 500 apartments and 1,000 inhabitants in Walden 7. Among these flats, one is available for holiday lets. A single-level, two-unit space on the 12th floor, it belongs to Gabor and Araceli, an architect who works for Bofill and a university administrator respectively. They themselves live in five units over two storeys immediately next door. Walden residents actively exploit the potential to connect and detach units, and the largest apartment in the building is rumoured to be eight units on the upper two floors (Gabor shot his eyes to the ceiling as he told me of such profligacy). On my arrival in the building, I was met in the lobby by Araceli. The route to the flat seemed convoluted, but she insisted I would not get lost because I would be able to orient myself by reference to the exterior of the building. Viewed from the outside, Walden suggests a closed fortress, but once inside there are views at every turn and in some spots it is possible to see out of the block in two directions. That said, navigation is still not that easy for those of us without much sense of direction. I spent several hours walking the building, but I never quite figured out where I was going. Arriving back at the lifts remained a matter of chance.

In Bofill’s original design, Walden’s units had a scant number of uniformly small windows. This approach was inspired by the vernacular architecture of hot southern climes of the kind Barcelona enjoys perhaps four, but certainly not twelve months a year. Since then, residents have been allowed to open their apartments to the sunshine so long as they conform to a particular brick-strutted model. Gabor and Araceli’s rental has a large window with fabulous views of the hills to the east. Walden’s construction is very basic. Significantly there is no central heating system and each flat has to be furnished with its own boiler and air conditioner. Gabor described the units as ‘raw space’ that require significant design input from the inhabitants (his own preference is for a wood-floored, white-walled soft minimalism that makes for a very pleasant short stay). This sets them apart from apartments like those in Le Corbusier’s Unite d’Habitation, for example, which were conceived as machines for living. Where Le Corbusier designed inbuilt storage and created suites of rooms destined for particular purposes, Bofill offered nothing, except, rather bizarrely, a bath built into the centre of the living space, a theatrical feature that most Walden residents jettisoned long ago. Bofill has explicitly declared himself against modernist architecture, believing that it is an ‘anti-city approach’. ‘Le Corbusier wanted to make the city into a machine, divide it into functional parts,’ he said, ‘but in the end there was nothing alive in it.’2

That Bofill was able to start building without completing his architectural training was in part thanks to his father Emilio, who was a successful builder and developer. The finances behind Walden 7 have not been made public, but Bofill senior was certainly involved. Bofill father and son shared the same radical inclination and the building was intended to be social housing not in the sense of being publicly funded, but by virtue of its very low cost. Because the land was cheap and the construction was extremely basic, the individual cells could be sold for far less than the standard price for apartments in Barcelona at that time. The downside of this approach has been the building’s considerable wear and tear. It was originally covered in red tiles, but they were attached with an inappropriate adhesive and started falling from the surface soon after completion. Now they remain only on Walden’s small semi-circular balconies. Likely it was the immediate dilapidation that prevented the further four blocks being built. After years of neglect, in the mid 1990s the local government stepped in to restore the structure, but even now it seems to be in a state of perpetual repair.

Such technical failures might go someway to explaining the complex relationship between Walden 7 and Bofill’s current practice. Bofill has lived and worked in a converted cement factory immediately next door to the block since it opened. An extraordinary industrial cathedral infiltrated by a lush tropical garden, the ‘Fabrica’ is visible from many of the block’s apartments and walkways. According to Gabor, around 15% of the Taller Bofill’s current staff live in Walden, as does one of his ex-wives who is married to a partner in the practice, yet Bofill himself has not visited the building in decades. Nor did he agree to meet me to talk about the project. People who know him well told me that Bofill prefers to look forward rather than back, but that is not enough to explain the oddity of his dual proximity and disassociation.

In the decade after completing Walden 7 Bofill became the darling of the French government, building a number of large social housing projects around Paris and beyond. Moving away from the geometric vernacular-influenced styles of his early years, of which Walden was the culmination, he began to tuck modest housing behind vast classical facades. The most significant of these developments is Antigone in Montpellier, a 36-hectare plot consisting of neo-classical crescents and boulevards containing apartments, offices and shops. By the time he turned 40 in 1979, Bofill was already something of a starchitect (before the term existed). The French now regard Antigone and its ilk with mixed feelings and Bofill’s subsequent reputation has been somewhat controversial.

Walden 7 may have a chequered history as well, but now it appears that time is being kind. According to the lore of its current residents, when it was freshly built Walden attracted outsiders – ‘prostitutes and transsexuals’ – but these days it is filled with people who work in the media and academics. As in J.G. Ballard’s High Rise (1975), there is a hierarchy between the building’s floors: while inhabitants lower down get poor views from the exterior windows and little light through those that face the lobby, those up on the 12th floor, as I was during my stay, can survey the hills surrounding the city and enjoy sunshine flooding through the back of their apartments. Probably an indirect result, the public spaces on top floors are abundant with pot plants and garden furniture, while those lower down are neglected by comparison. That said, Walden is pretty well-tended top to bottom these days. Part of the international craze for Utopian housing projects, the building has an active residents’ association who have created facilities such as a book exchange in the lobby, children’s art classes and a nude sunbathing spot on the roof. According to Gabor, Waldenites who start out with apartments on lower floors aspire to elevate to larger spaces at higher altitudes. Rather than a place to house people on the margins of society, now it is a structure within which to enact social betterment.

On the evening of my stay, just before sunset, I made my way to the top of the building to enjoy the view. It had been raining, but the clouds parted just in time to drench the building in pink light, turning it an even deeper shade of red. Walden 7’s roof is devoted to a communal garden, complete with two swimming pools. It was too cold for bathing, and instead I shared the view with an amiable pair of spliff-smoking teenagers. The building might have been gentrified, but it remains relatively inexpensive and has a decidedly friendly, community-focused feel. Residents sit on the walkways outside their flats and leave their front doors open for fresh air. While Bofill may feel ambivalent about the Walden project, he has generated a format that shows every sign of working. The Taller Bofill didn’t ignite a social revolution, but, over the last 40 years, society has come round to the way of living that they proposed.

- From an interview with Ricardo Bofill by Carson Chan, ‘Ricardo Bofill: The Future of the Past’, Mono.Kultur no.36, Spring 2014.

- Ibid.